“If this team have to drop out of racing next year, as is rumoured”, concluded Denis Jenkinson, “it will be a sad day for long-distance racing, but they will have left behind a standard for all to aim at.”

A familiar theme for sports car racing, and Porsche. He was writing about John Wyer Automotive’s 917s, having just witnessed the blue and orange cars of Jackie Oliver and Derek Bell cross the finishing line at Spa-Francorchamps less than half a second apart following the 1971 1000kms of Francorchamps.

A perfect demonstration, Jenks called it. It was a contrived finish, as Bell was ordered to remain behind compatriot Oliver, but motor sport is a history of staged finishes.

That doesn’t take away from the brilliant spectacle of what had just happened. This was some of the world’s greatest sports car proponents, in some of the most stunning, feared, spectacular and rapid cars in history, on one of the deadliest circuits in the world. Burnenville, Masta Kink, no “‘safety’ chicane put in at Malmedy last summer for the puny little Grand Prix cars and their timid drivers”, as Jenks put it.

A field full of Group 5 and 6 Porsche 917s, Alfa Romeo T33s, Ferrari 512Ms, 312Ps, and Lola T70s is breathtaking enough at historic events; when that pack is more concerned about winning than avoiding a scrap, it makes the hairs on the back of your neck stand on end. Consider the eventual podium: Rodríguez/Oliver, Siffert/Bell, Pescarolo/de Adamich.

It’s easy to see why DSJ was in such colourful and satisfied mood. That it would be the last time the five-litre Group 6 cars would contest the great race was not lost on those braving the dank Ardennes forest.

The Porsches had been dominant all season so far, winning five of the opening six races – only the little Alfa had broken the run at Brands Hatch. Fortune played its part in Kent, but there was little chance for the Alfa to match the sheer power of Porsche around Spa.

Twelve months earlier, Siffert and Rodriguez had been trading door paint and more as they flicked left at the foot of Eau Rouge and up towards Radillion. It was little different, if a little less dramatic, this time. Door handles were scraped as Eau Rouge hoved into view. Through they made it, this year line astern, and off into the distance they disappeared.

Not even the great Ickx could keep up. Not even in the rain, Ickx’s great advantage. Still, there he was, a drop of red in a sea of Porsche, behind those two friendly rivals but ahead of Marko and Kauhsen.

Rodriguez and Siffert surely couldn’t keep the speed up, nor the much-needed concentration. They had hot-footed it across the channel to and from the International Trophy at Silverstone the day before, paired at BRM. Pescarolo had done likewise, whereas Ferrari’s late withdrawal due to ‘an industrial dispute’ gave Ickx and Clay Regazzoni and somewhat quieter weekend.

But the frighteningly fast record-setting times continued unabated. Likewise the Porsches. Ickx shipped seven seconds a lap in his three-litre Ferrari compared to the five-litre Porsches. His hope was the pitstops, and his ability to run five laps longer. But it was a hopeless cause unless the JWA slipped up again, like at Brands Hatch.

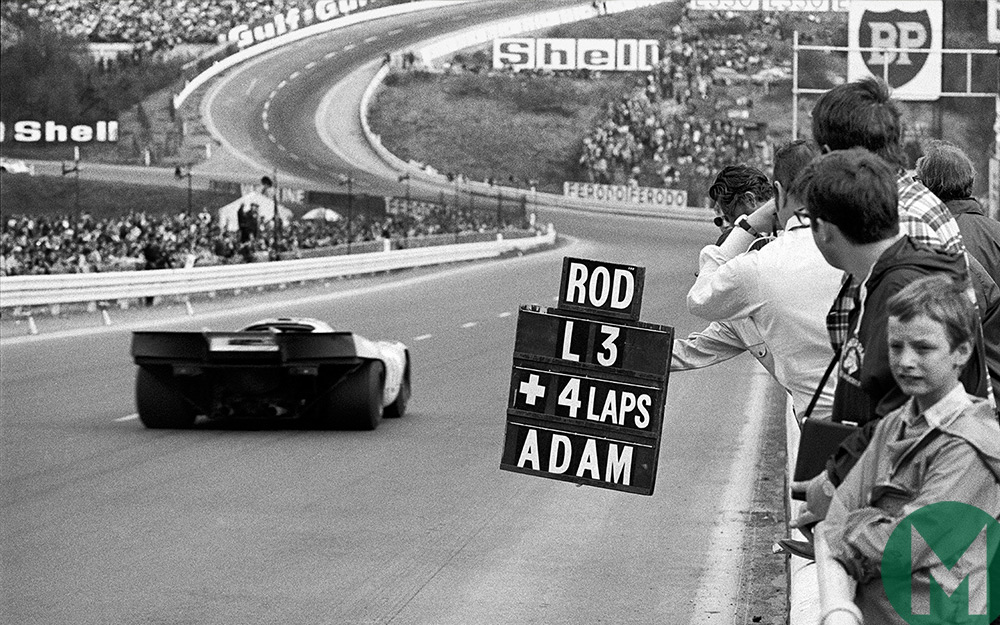

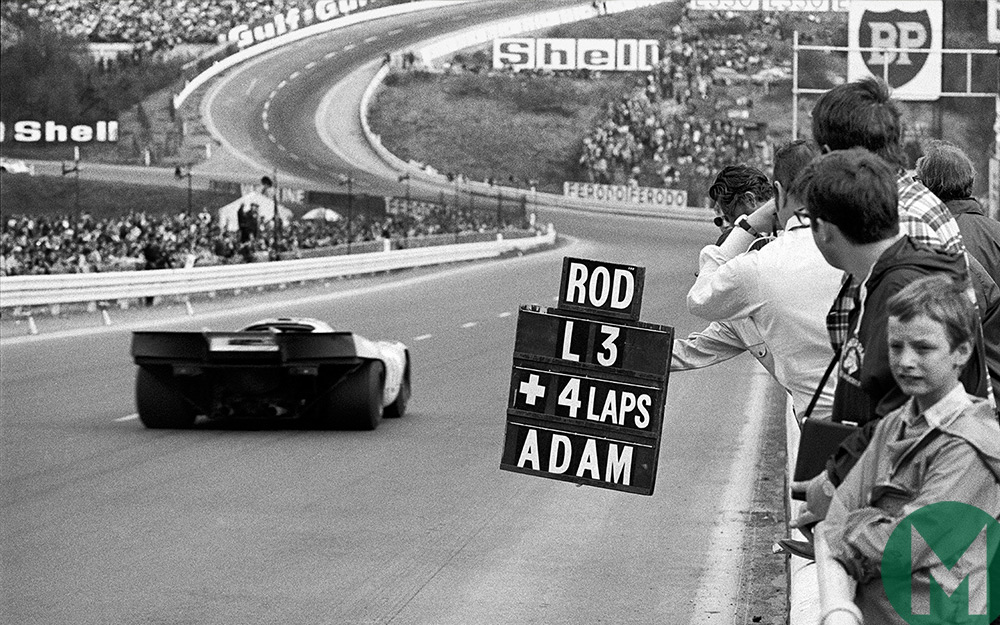

Nose to tail, lap after lap, when it came to handing over there was barely seconds in it. Oliver acclimatised more quickly than Bell, stretching those few seconds to more than 20. But Bell closed and closed, but soon ordered to hold station by David Yorke, Wyer’s team manager.

The decision didn’t go down well with Siffert, according to Jacques Deschenaux, writer and friend of Jo’s. “Seppi told Yorke he wanted to win, what was he doing? He was really mad!” he told David Tremayne in 1991. “He dragged me down the pit lane – JW’s pit was at the top – and down to Claude Haldi’s pit. We grabbed his signalling board and so Derek got an official board from Porsche at the top of the hill and another from us at the bottom, urging him on!

“Seppi was so disappointed. He was crying with frustration.”

There was some comfort for the Swiss. The lap record was his, no longer Pedro’s. He (most likely ‘they’, they really were that close) – had lapped the 8.7-mile circuit at an average speed of 162mph, recording a time a full two seconds faster than Pedro had gone the year before. The record stood for just two years, when Pescarolo trimmed a further second off in a Matra.