Think Formula E is a revolution? A similar concept almost came to fruition two decades ago – with Bernie’s blessing

Formula E is late. Twenty years so. In the mid ’80s and early ‘90s, a passionate and talented few set about stripping away the perception that electric propulsion is good for only milk floats. So talented were they that each has gone on to bigger and better things.

The best-known players in this unintentionally secretive project, named by the acronym ZERO for Zero Emissions Racing Organisation, were Bill Gibson and Eric Broadley, the former of Zytek (now Gibson), the latter of Lola. It was Gibson who devised ZERO in partnership with Gerard Sauer, a Dutchman who moved to the UK to form ADA Engineering (later sold to Chris Crawford) to break into racing.

“Bill and I were working together on a project for a client,” the semi-retired Sauer explains now, the pair ironically having also worked on a project for Lucas Spark Plug Co. “We kicked the ZERO idea around a bit, we knew electrical motors were applicable to vehicles but they had a rather staid image – milk floats, golf carts, that kind of thing. We thought, ‘why don’t we try between all of us, Sheffield University and Zytek to design a vehicle that can show that electric vehicles don’t have to be slow at all?’”

When approached, Broadley supposedly soon saw the potential for the project and Lola. His first involvement was to assign ZERO to one of his young designers, one now with a reputation for pushing the boundaries of the norm. His name was Ben Bowlby.

“Ben did a superb job,” Sauer recalls. “He designed a really nice 9-1 reduction box.

“The concept of the car was based on wheel-differential steering. We got quite far with the calculations, I think the steering had eight degrees either way but then all the other steering would come from wheel-differential steering. By vectoring the motors on each wheel, making one run faster than the others, you would corner. The big benefit was that you could achieve higher cornering speed for lower slip angles. It was very clever.”

Sauer had hoped that would be an avenue Formula E explored, or indeed does in the future. “That would be the next step, as well as battery technology,” he believes.

If Formula E now suffers from accusations of being too slow, ZERO took aim at Formula 3 pace. And there’d be no changing cars – a gripe Sauer has now of Formula E: “It’s ridiculous” – but short races.

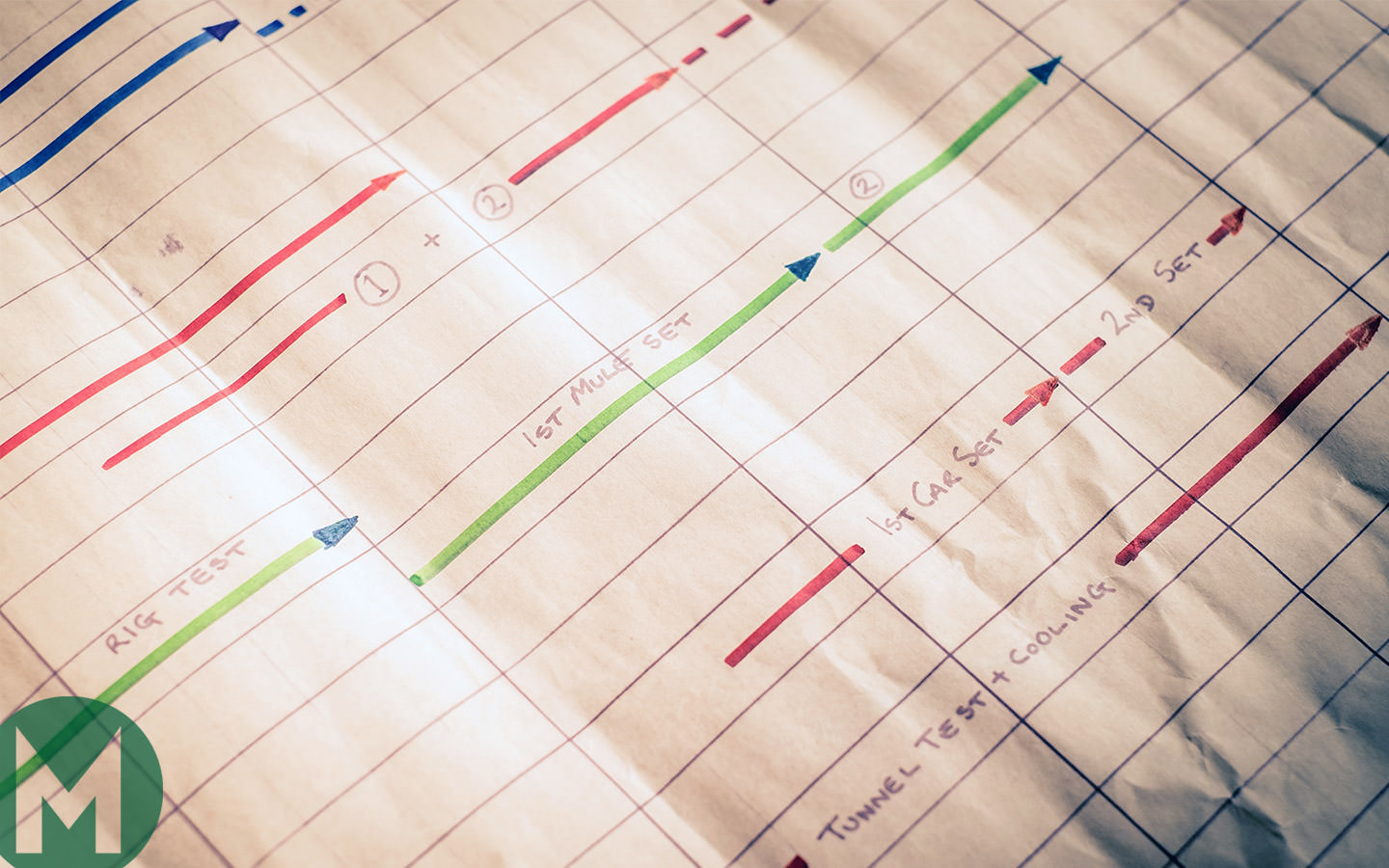

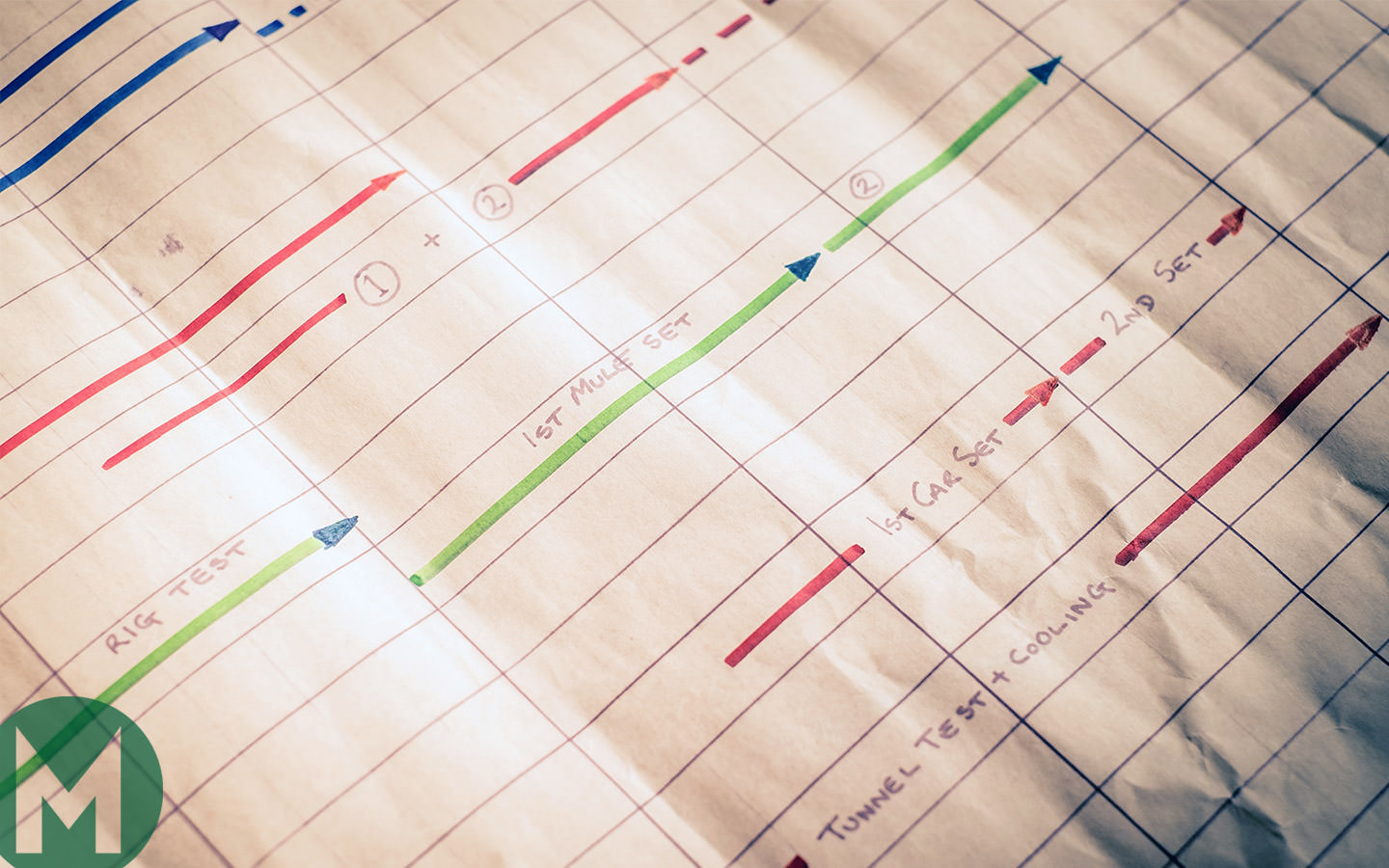

“We had some help from Jackie Stewart, he gave us data from the Formula 3 car they were running and Formula 3000. We knew then what we had to shoot for. The guys did some planning for what it would need to do to complete say 10 laps, I don’t think we got to that but we certainly reached six or seven on a pack.

“It looked a proposition. The energy density of the battery then just wasn’t as good as it is today; it was really in its infancy. But it did show even with rudimentary calculations that an electric vehicle could achieve Formula 3 lap times around Donington Park, for example.”

There’d be no city centre pop-up circuits either, even Bernie Ecclestone’s interest was piqued. Conversations progressed and the ZERO team were told to contact Paddy McNally in Geneva about supporting European Grands Prix.

“Obviously Bernie didn’t know much about electric racing and electric cars but he was intrigued by it. I can’t remember the exact figures now but Paddy said each car would need to pay 11 grand to race. That was quite rich. We had potential sponsors in Powergen; it hadn’t committed to anything but there were serious discussions going on.”

The sponsorship never came to fruition, internal politics at Powergen put paid to that, and with it ZERO. But the car certainly progressed.

“Moves were made towards building the motors, it was really marching forwards. We did some modelling and bench testing and it looked extremely promising. The small motors later became the foundation for work Bill’s lot did.

“We weighed the Formula 3 upright, brake disc, caliper and assembly, and it came in at about 25lbs, then we redesigned the wheel for purpose with the motor as the upright anchor points and it weighed something like 27lbs.”

Yet nobody knew. There’s little that remains in public, if it ever got as far as public knowledge at the time. It’s a world away from the modern way of racing, when a mere idea takes up column inches in news pages.

“We were never able to move it beyond breaking the metal and cut and shut things, so it didn’t seem much point to make any noise when we couldn’t follow it through. It was very real, at a wonderful time. Bill and Eric were sparking off each other, and the three of us drove it forward at a hell of a pace. Within a year we had a bunch of technology together that was really mouth-watering.

“It was a big blow when it went away, but all the people involved claimed leading positions in industry: Phil Mellor went to Bristol University, Ed Lukaszewski went to Mactech, Pete Monkhouse went with Bill. It was an exciting time, it really was.”

Sauer himself has since been a key figure in the hybrid vehicle industry, even being enlisted by Ken Livingstone to develop a hybrid bus. ZERO didn’t fully disappear from their minds for the best part of a decade, but Lola’s Formula 1 project took priority and electric racing fell by the wayside.

“The last time we really said we should revisit it was in 2001. My other half always said we were too far ahead of ourselves. Formula E sort of proved that.”