Instead he fell four points shy as the rear-engined British cars put their shoulders to the door.

Not that Enzo Ferrari was overly appreciative in his melodramatic My Terrible Joys memoir of 1962: “Brooks, who has given up racing to be a car salesman or a dentist – I am not sure which – appeared in the limelight as a great stylist and a man who used his brains. Subsequently, although possessing ability and skill, he became far too cautious for himself and others.”

It is undeniable: Brooks did not fit the gung-ho template of Ferrari’s preferred garibaldini; his decision to pit to check if his car had been damaged at Sebring was indicative of that. He had come an injurious cropper twice in compromised cars and vowed never to do so again. He stayed true even when tempted by the sport’s greatest prize.

Stirling Moss – he was his own man, too –would have continued, likely unabated. But who’s to say that stopping wasn’t the braver call? Not I.

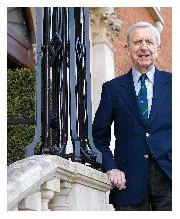

Famille Fearnley, an earlier version, was at Aintree the day that Moss and Brooks became inseparable as the first to win a world championship GP in a British car. The former got/gets most of the credit – some winners are more joint than others – but Brooks’ fortitude must never be forgotten. He qualified on the front row despite having a hole in a thigh that “you could put your fist into” – legacy of an Aston Martin/Le Mans cropper – and started the race on the mutual understanding that his Vanwall would become Moss’s should he need it. When the call came the normally lithe Brooks – he had lost a stone that he could ill afford to – had to be helped from the high-sided cockpit. (He is today back at his 1950s racing weight.)

Moss was the puncher who loved a scrap; Brooks was the boxer who picked his shots: witness the 1957 Nürburgring 1000km, the 1958 German GP and the 1959 French GP.

He drove up to his (very high) limit and no further; it mattered not whether a track was delineated by straw bales, woods or brick walls. On perilous road circuits that caused ‘aerodrome chancers’ to huff and to puff, Brooks exuded the right stuff: ‘safe’ in his bubble of skill. He made the extremely difficult look ridiculously easy.