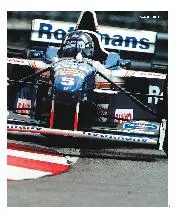

The bolstered confidence certainly worked for Hill in the first half of the season – although a serious wobble from mid-summer allowed Villeneuve to take the title to the wire. After a fantastic win at Estoril, probably Villeneuve’s best performance in an F1 car, he’d closed to within nine points of a jittery Hill as they headed to Japan. Damon wasn’t going to blow it, was he? No, as it happened. The emphatic way he clinched his title showed all of Hill’s best qualities and his significant depth of character – especially as he knew it would be his last time in a Williams. Like Nelson Piquet, Nigel Mansell and Alain Prost before him, Damon wouldn’t defend his title in a team that had never really found a driver it approved of more than Alan Jones, its first world champion from way back in 1980.

‘Has Hill been dumped?’ screamed Autosport’s front cover the week of the German GP. The writer who broke the story, Andrew Benson, was made to sweat but stood firm even when Damon threw him out of the Williams motorhome at Hockenheim – and between Spa and Monza, Hill discovered the story was true when Frank Williams called to tell him Heinz-Harald Frentzen would replace him for 1997. Rumours linking the German had swirled since the autumn of 1995, but Hill had always disregarded them. Exactly when Frentzen was signed remains disputed. It has been said the deal was completed during 1995 in the midst of Hill’s struggles against Schumacher’s Benetton. But if that’s the case why did Frank Williams entertain negotiations for a new deal with Hill during 1996? Those talks were not handled well from Hill’s side, as Head explains, and if Williams’s mind wasn’t already made up they appear to have contributed to the brutal final outcome.

Schumacher and Hill clash at Silverstone in ’95. The Williams-Frentzen deal was said to have been done that year

Bongarts/Getty Images

“I cannot remember exactly when Heinz-Harald Frenzen was signed for 1997,” claims the legendary technical director and team co-founder. “Frank tended to regard drivers as his area of decision. Sometimes he discussed these matters with me, but mostly he dealt with drivers alone, and I was informed after his decision and action.

“Damon did not help himself by distancing himself from dealing with Frank directly, and sending in his manager Michael Breen, who put his briefcase on Frank’s desk, told Frank that many teams were chasing Damon, and that ‘they’ (presumably Damon and he) would start talking to Frank on offers above $15m.

“Since Damon had no drive at all when we engaged him as a test driver for the active ride project in 1992, and had later negotiated a contract with him for $5m, Frank thought that this demand was ‘a bit rich’. Since we were a private team, with no manufacturer backing as far as driver salaries went, it was way more that we could afford.

“I remember that I tapped on the door and walked into Frank’s office when the conversation with Michael Breen was going on, and there was a long silence from Frank. Then he said to Michael, quietly: ‘Would you please take your briefcase off my desk, you know your way out, I suggest you go and talk to these other teams. If you should choose to come back, willing to negotiate a lower sum, my door will be open.’ At that Michael left.”