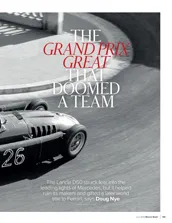

Designer Aurelio Lampredi’s Ferrari 500 Formula 2 car – promoted to GP car by external forces – was just powerful enough and sweet-handling even so.

Taruffi liked it and so it suited him to be in Enzo’s good books having supplied the marque with its first major win in the Americas: the 1951 Carrera Panamericana, co-driven by Luigi Chinetti Snr.

Though he was no match for sensational team leader Alberto Ascari and generally shaded for speed by Giuseppe Farina, Taruffi took his chance when he got it and stayed around long enough to capitilise on it.

Ascari was absent contesting the Indianapolis 500 for Ferrari and his mentor Luigi Villoresi had been injured in a road accident just prior to the 1952 Swiss Grand Prix at Bremgarten on 18 May.

So Farina qualified on pole – 2.6sec faster than Taruffi – and led the early stages before an engine problem forced him to pit. He commandeered newcomer André Simon’s car, which also burst underneath him.

Debut ’52 championship race win was followed by more strong results, including second to Ascari (right) at Silverstone

Express/Express/Getty Images

Thus Taruffi, in typically measured fashion, scored the first win of the World Championship’s F2 interregnum.

The returning Ascari put that performance into context by scoring nine successive World Championship Grands Prix wins, but Taruffi seemed unusually settled. Whereas Farina railed against the former’s supremacy and primacy, Taruffi reeled off a string of strong results – third in France, second in Britain, fourth in Germany – to be third in the final standings.

Whereupon he fell out with Enzo over which car might better suit the demands of a Targa Florio and joined pre-eminent designer Vittorio Jano at (overly) ambitious Lancia in 1953.

Taruffi, who would win the 1954 Targa for Lancia, was a hard man to pin down.