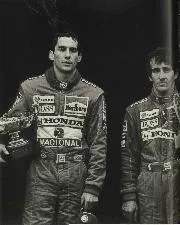

As the first race of the season approached, speculation mounted as to which of the two chargers would claim supremacy.

In some ways Senna was still the coming man, a challenger to the undisputed heavyweight Prost. To others, the Brazilian had long since arrived. He just needed the machinery to prove it.

The two would go at it hammer and tongs all year. By the time F1 fraternity touched down in Suzuka, Senna simply had to win and he was champion. By virtue of the “eleven best results” scoring system employed that year, Prost could only add three points to his total even if he won in Japan.

In qualifying, Senna maintained his imperious one-lap form of that year, besting the other McLaren by 0.3sec. The Brazilian had scored 13 poles that season, whilst Prost had two.

“Alain always accepted and never hid the fact that Ayrton on one lap on was absolutely unbelievably fast, with the way he managed to build up the engine revs in a corner” says Ramirez. “[Prost] tried to do the same but never managed.”

It was what happened on race day that really mattered though, and on Sundays the McLaren pair were much more closely matched.

“He didn’t tolerate the mistakes of the team and his mistakes he would tolerate even less.”

Senna lined up first on the grid with Prost alongside him, with the Ferrari of Gerhard Berger just behind in 3rd.

The poleman, as Murray Walker put it, had been “tight as a violin string” pre-race. This might just have contributed to what happened next.

As the lights went out, as rev-limiters hit their peak and Goodyear tyres squealed, most of the field got away well – apart from Senna.

The car juddered as the Brazilian suffered every racing driver’s nightmare. He’d stalled it.

The onrushing field swarmed around him, with Berger just managing to swerve and avoid the polesitter. It was only the Austrian’s razor-sharp reactions that prevented a collision.

Luckily for Senna, the Suzuka pit straight is on a slope. As he waved his arms frantically in the air – to warn other oncoming drivers – his car began to roll down the hill.