Ever since then – at least until the 2020 rear slick arrived – the M1 has been unable to use its strong points and has been hurt by its weak points.

Consider all the multiple different chassis the factory Yamaha team used between 2016 and 2019, trying to find more grip.

During that period Rossi and Viñales tried this chassis and that chassis, then kept swapping this way and that from one track to the nest. One year they ended the season by switching to the previous year’s chassis at the last race. That’s what you call confusion!

Meanwhile the satellite teams – Tech 3 and then Petronas SRT– kept racing with what they’d got. Their bikes remained mostly unchanged, because the factory policy is to develop the bike with its official team and leave its indie team on older, lower-spec kit.

Even better, the year-old bikes given to Tech 3 and Petronas (with the exception of Quartararo this year) have a full season’s development behind them, with a full season’s data. So they are in the best state they can be in. Meanwhile the factory riders start anew every season, building data, building knowhow, race by race.

Occasionally the indie riders complain they wanted the later kit, but mostly they continue turning laps with what they have. And this is the secret to success in motorcycle racing.

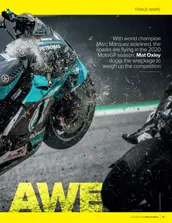

Rossi chases Petronas riders Fabio Quartararo and Franco Morbidelli on Sunday

Petronas SRT

Bike racing is 99 per cent about feel, so the more laps you ride without changing the set-up, the more you get to know your bike and the more intimate you become with its behaviour, so when the front tyre slides you’re already expecting it, so you’re ready to do whatever you need to save that slide.

When you go out to ride with a new chassis or significantly different settings you have none of that intimate knowledge, none of that ability to predict the motorcycle’s behaviour, so when the bike does something bad it mostly catches you by surprise.

There is proof to all of this. Look at the results of indie Yamaha riders over the years: Quartararo, Franco Morbidelli, Johann Zarco, Crutchlow, Bradley Smith, Andrea Dovizioso and so on.

Their achievements on indie M1s are proof of the fact that it’s easier for a rider to find a hundredth from within himself than from the motorcycle. True, Rossi will have 2021 bikes next year, but he won’t have engineers thrusting new bits and pieces at him all the time, which may or may not work.