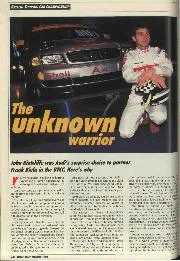

The Unknown Warrior

John Bintcliffe was Audi's surprise choice to partner Frank Biela in the BTCC. Here's why You've no money. You have no karting experience or family background in motorsport to call…

The last time I saw Silverstone managing director Stuart Pringle in person, he was dusting off his motor cycle at the Northamptonshire circuit, ready for the ride home at the end of a long, hot day. He had generously given up his afternoon to offer me a tour of the circuit just ahead of the 2018 British Grand Prix.

Affable and efficient, his attention to detail was astounding as we slowly lapped the circuit: the grass required watering here; the kerbs needed a touch-up there. He greeted all the workers out on track by name.

His biggest concern was the asphalt – freshly laid earlier that year and now sweltering in the summer’s record temperatures. The fear, he said, was that the Formula 1 trucks and low-loaders would park on the track by the pits to disgorge their cargo and perhaps chew up the surface. He was contemplating being on site himself as they arrived from Austria, to marshal the drivers and brook no dissent.

But away from such minutiae, the former tank commander was also playing a high-stakes game of poker with the most powerful vested-interest groups in the sport. A year previous he had been the driving force in activating a break clause in Silverstone’s contract with Formula 1’s commercial rights holder. By doing so he was effectively calling time on the British Grand Prix, since under the terms of the contract the 2019 race would be the last – unless a new deal was agreed beforehand.

It was a huge gamble: Pringle was betting the farm that he would be able to strike a better deal with new owner Liberty than the one he currently had. When I put this to him, he claimed that he didn’t consider his move to be a gamble, for the simple reason that the status quo could not continue because the cost of hosting the race had become so great.

Even so, I think I might have detected a small sigh of relief ahead of this year’s British Grand Prix when Pringle hosted a press conference with F1 boss Chase Carey and John Grant, chairman of the BRDC (which ultimately owns the track). It heralded a joint announcement that a new deal had been agreed to keep the race at Silverstone until at least 2025.

“The prospect of not hosting a grand prix at Silverstone would have been devastating for everyone in the sport,” said Pringle. “I am delighted that we are here today, on the eve of what is sure to be a fantastic event [in 2019], making this positive announcement about the future.”

Clearly it is a big win for Silverstone, for British racing fans, and for the country as a whole – the UK would have been all the poorer without its own round of the Formula 1 World Championship. It is also a big win for Pringle: he made a brave call and it looks to

have paid off.

It is a victory also for the Silverstone management, which some argue had in the past been run more like a smart golf club than as a modern, multi-million pound business responsible for one of Britain’s most popular sporting events. I will never forget a quote I was given by a BRDC member, on condition of anonymity, when I was writing about the club a couple of years ago. Important decisions, he said, could never be made because “members are racing drivers, not necessarily businessmen. You get a situation where people who are trying to work together are saying things like: ‘I’m not working with him – he ran me off at Copse in 1972’.”

That sort of amateur ethos might be appealing to us fans, but in reality it can’t have a place in the modern world of motor sport. When you are up against a hard-nosed, professional outfit like Liberty, it is vital to remember that gladiatorial, winner-takes-all combat doesn’t happen on the racetrack alone, but also in the boardroom.

No one wants the suits and bean-counters to take over. After all, we love racing because we love the sport. But equally, you can’t turn up to a contract negotiation armed with a passion for racing and a sense of fair play. It looks like Silverstone grasped this and has reaped the reward.

The big question now is what other grand prix circuits will demand from Liberty. Under the old contract, signed when Bernie Ecclestone was running things, Silverstone was set to pay £26 million to stage the race. The new hosting fee is thought to be in the region of £20 million a year or £100 million over the five-year term. If it transpires that as well as a reduced hosting fee, Silverstone has wrung other significant concessions, such as a share of merchandising revenue, for example, you can expect other venues around the world to demand something similar.

Pringle’s gamble might turn out to be the start rather than the end of Liberty’s circuit negotiations.

Joe Dunn, editor

Follow Joe on Twitter @joedunn90