By this time Hailwood had acquired his first personal road car. “It was a red Ford Consul and I got it all fitted out with the really hot stuff. The only trouble was that, while I was driving it home from the place where the conversion was carried out, the crankshaft fell through the bottom of the sump.” Disillusioned with cars of this nature, Mike turned his attention to Jaguars and acquired one of the very first 3.8-litre Mk. 2 saloons—”terrific value for money. I had about three of them and did about 80,000 miles in one of them. I had one of them fitted with a 35-gallon tank which I used to top up for free at race meetings and this allowed me to drive right across Europe without refuelling. When I got to the next race I’d just fill up again and come back! They were absolutely no trouble at all, which is more than I can say for the first E-type owned. I bought one of the first 60 pre-production roadsters . . . it was absolutely appalling. In the rain it was just like driving a swimming pool. I didn’t touch Jaguars for a while after that.”

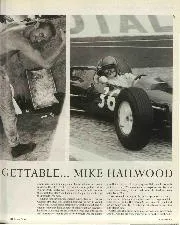

The fact that Hailwood has always been able to indulge his taste when it comes to road machinery was initially a reflection on his family’s wealth, although it didn’t take long for the earnings from a fast-mushrooming racing career to finance any of his requirements. Mike was born into wealth and made a lot more of it by his own honest endeavours— and that probably explains why success has left him pleasant and uncomplicated. On the other hand he becomes very firm if one suggests that his early success was the result of his father being able to afford the best machinery for him to ride, correctly pointing out that money can’t buy ability. In any case, by the start of the 1959 season he was offered works 125 and 250 c.c. Ducatis on which he was never beaten in British Championship events and finished fourth in the 250 World Championship despite missing a couple of rounds. What is more, at the age of 19, Mike became the youngest ever World Championship race winner for the first time when he triumphed in the 125 c.c. Ulster Grand Prix at Dundrod. He was also to become the youngest ever World Champion and TT winner.

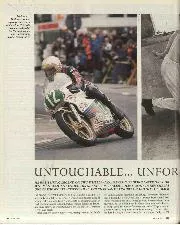

Hailwood winning the 1967 Senior TT – his first win on the island was in 1961, his last in 1979

Honda

Hailwood’s success story is so comprehensive that a record of his two-wheel victories on their own would simply read like a scorecard. In 1961 he became the first man to win three TTs in a week and won the 500 c.c. TT on a single-cylinder Norton after Gary Hocking on the Italian multi-cylinder MV Agusta broke down. Then, in 1962, he joined the team which was to take him to stardom and the reputation as the finest motorcycle racer of all time.

Mike Hailwood signed for the Italian MV team, run by the autocratic Count Dominico Agusta and in many ways the two-wheeled equivalent of Ferrari. It was a successful, if slightly uneasy alliance, for Mike wasn’t particularly sympathetic to the Italian way of life—”I really couldn’t stand living in Italy, so I never did, even when I rode for MV”—and Count Agusta tended to rub him up the wrong way on a great number of occasions.

“I tore the contract up, threw it over this guy’s desk and went back to my hotel”

“I remember once he kept me waiting for hours on end, to sort out money or something. It was all a bit silly really, he did it all for effect. The little accountant guy kept telling me ‘yes, well the Count is very busy at the moment, he’ll see you soon’ but I wasn’t messing around with him and told them that if he didn’t appear and agree my money then I’d tear up my contract there and then. He didn’t appear, so I tore the contract up, threw it over this guy’s desk and went back to my hotel. I suppose it was all a bit silly really, but it wasn’t anything that lasted for long. They came chasing after me, picking bits of the contract up off the floor and sticking it all together again.” From most racing drivers one might be tempted to consider that a tall story, somewhat embellished with the passing of time. But with Mike you could be certain it was true. “There you are,” he smiled as he fumbled his way through a pile of papers and triumphantly pulled out a dog-eared piece of paper criss-crossed with Sellotape, “that’s the one”.