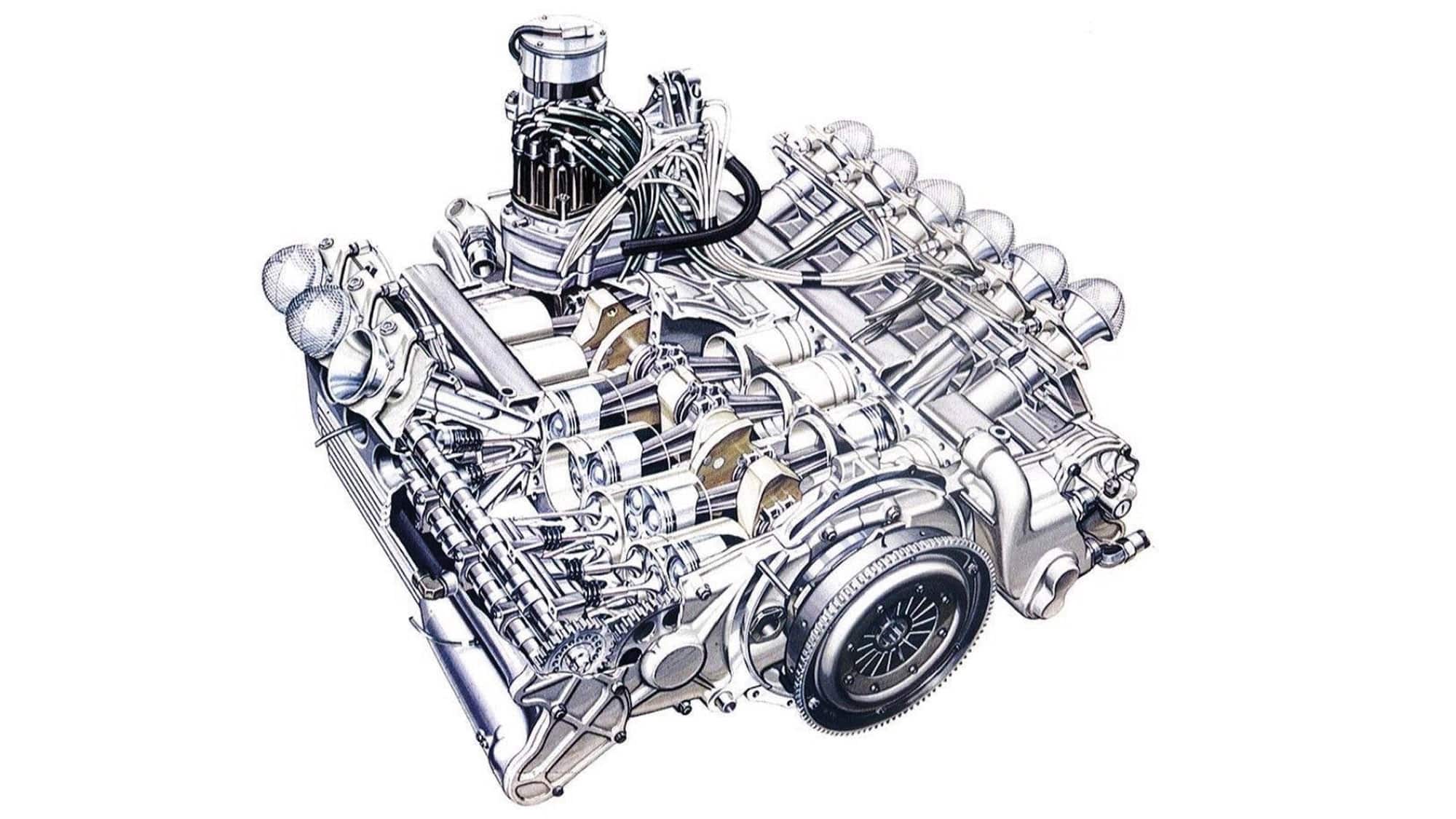

The flat 12 engine that powered Ferrari to '70s F1 triumph

In the mid to late 1970s Ferrari painted the town red, with world titles for Niki Lauda and Jody Scheckter and an incredible 1-2 in ’79. But as Mark Hughes reveals, a major part of that success was the f lat-12 engine, which powered the Scuderia’s 37 wins over 10 seasons

Hoch Zwei/Corbis via Getty Images

The best, most successful V12 in F1 history was actually a flat one, Mauro Forghieri’s 180- degree masterpiece for Ferrari, which served the team from the beginning of 1970 to the end of 1980. It was the foundation of the team’s glorious period of success in the mid to late ’70s, powering the Scuderia to Constructors’ titles in 1975, ’76, ’77 and ’79 and making world champions out of Niki Lauda and Jody Scheckter. Other legends to have won grands prix with it comprise Jacky Ickx, Clay Regazzoni, Mario Andretti, Carlos Reutemann and Gilles Villeneuve. Quite a roll call.

Its distinctive blare trailed the triumphant Ickx-Regazzoni 1-2 on its first win in Austria 1970 just as it did its last one, Villeneuve’s wet weather demonstration at Watkins Glen ’79. They bookended 35 other victories. Good power, beautiful torque delivery, eventual rocksolid reliability – and a layout that conferred both a lower centre of gravity and a better airflow to the rear wing than the rival Cosworth DFV V8 cars. This and a weight penalty of just 15kg over the DFV despite four more cylinders, pistons, conrods, greater length, etc, made it a minor miracle of engineering for its time.

“Good power, beautiful torque delivery, eventual reliability”

It was the first Fiat-funded F1 Ferrari engine and there is a significance to that. The late ’60s had been a financial struggle for an independent Ferrari. It was putting a sheen upon a tired old structure with long-in-the-tooth V12 engines which dated back to the 1950s. Well down on power to the DFVs, way too heavy and requiring ridiculous quantities of cooling, it was only Forghieri’s great chassis and Chris Amon’s driving genius that had kept them in play at all.

Forghieri had been badgering his boss and tormentor Enzo Ferrari to give him an R&D department to create a modern Ferrari engine ever since he first set eyes on the Cosworth DFV in 1967 and understood its implications. “But Mr Ferrari faced certain financial restrictions at the time,” recounted Forghieri in 2013. “So I had said before the 1968 season, ‘OK, well if we can’t do a new engine can we at least just concentrate on F1? Rather than F1, sports cars, Can-Am, F2, even hillclimbs. If we do this, I am sure we can win at least three grands prix.’ Unfortunately, for a number of reasons we won only once and so at the end of the season I offered my resignation.”

But the shrewd Old Man wasn’t ready to receive it. “He said, ‘No, you are not resigning from anything. You will go to Modena and do what you ask about making a modern engine.’ The Fiat money was coming and the whole company was now able to race in a much more serious way.” Forghieri spent 1969 not at the race track, but secreted away with five other engineers at the base in Modena, remote from the politics of the main factory. There they created the beautiful 1970 Ferrari 312B, at the heart of which was Forghieri’s flat-12. “I was so very, very, very lucky with the draughtsmen and technicians I had around me – people like Franco Rocchi, of a high calibre that I could sit and discuss my ideas with. We were more than the sum of our totals.”

Ferrari’s Mauro Forghieri, left, checks Niki Lauda’s 3-litre engine before the 1977 Austrian Grand Prix. A majority of teams were using the Cosworth DFV V8 at this time

Grand Prix Photo

What the DFV had made plain to Forghieri was that there were enormous gains to be made from minimising oil pumping losses and maximising the strength of combustion even if it meant compromise on total flow capacity. This informed his combustion chamber shape and valve angles and much time was spent on baffling the internals in a way which kept the oil flowing and not simply being churned. The engine even incorporated the DFV’s ‘tumble swirl’ trick whereby the inlet port pointed the mixture at the opposite cylinder wall at an angle which induced a swirling motion, making the mixture more volatile.

Internally, it represented the new school of DFV thinking and made Matra’s V12 – conceptually a Ferrari V12 copy, though very different in detail – outmoded in its philosophies of combustion and internal pumping efficiencies. Not to mention size and weight – the Matra weighed in at 26kg more than the flat-12. The BRM V12 of the time was even lighter than the Ferrari, but only because it had been under-specced on bearing sizes, which made it unreliable and unable to reach the sort of revs or power of the Ferrari.

So even though the Ferrari flat-12 and DFV V8 were entirely different in layout and shape, internally Forghieri’s motor shared much of the same thinking. By Forghieri’s admission, the DFV was by far the most influential factor in his engine’s design. The Cosworth needed less of everything – fuel, water, air, space – than existing designs despite delivering more grunt. But that was only partly because of its V8 layout. There was surely a way of combining that new thinking with more cylinders to make something even more potent.

Forghieri didn’t want to throw out the 12-cylinder baby with the efficiency bathwater. He believed he could surpass the engine of his inspiration by a greater number of smaller cylinders which would be laid out to lower the centre of gravity height. There was more than just F1 thinking behind the 180-degree layout, as Forghieri revealed: “It was conceived also to be an aircraft engine. Ferrari had an agreement with the Franklin aircraft company to make an engine which could be incorporated into the wing. Franklin went into receivership and it never happened but that’s where the idea of the flat layout came from. But it did bring the centre of gravity height down to around 3.5cm lower than a DFV.” It also made for a bigger space beneath the rear wing’s underside, potentially allowing it to work more powerfully.

The Ferrari pit at a damp Zandvoort in 1971 with Clay Regazzoni in the car in discussion with Mauro Forghieri. Jacky Ickx, seated, was picking up tips – he went on to win the race

Grand Prix Photo

“It is not a ‘boxer’ engine by the way,” Forghieri stresses. “A boxer engine has each opposing piston moving away and towards the other on the same throw. My engine retained the same sequence as a traditional V12 but the vee was laid out horizontally.”

The advantages of a 12-cylinder over an eight are very real, but so are its disadvantages, and the technology of the time limited the full exploitation of the former. The 3-litre capacity limit of the formula meant each cylinder was only 250cc (compared to 375cc for an eight). This drastically reduces the peak loadings on the rev-limiting components (pistons, rods, bearings and crank), as the inertia loads increase in square to the engine speeds.

Also, because the smaller pistons are not absorbing as much heat, the bore size can be increased and the stroke shortened, further reducing those stresses. At its 1970 introduction the flat-12’s bore to stroke ratio was 61/39%. That of the DFV was a less favourable 57/43%.

But the greater engine speeds will demand more fuel, it will be bigger and heavier and its long, slim shape will be less conducive to being used as part of the structural strength of the car. The frictional losses will be greater because of the greater number of moving parts, although Forghieri minimised this penalty by ambitiously running just four main bearings (in bronze) – rather than the traditional 7 of a V12 – in which to carry the crankshaft. One of the keys to the motor’s small weight penalty over the more compact DFV was the use of titanium conrods rather than the forged steel of the Cosworth. This was cutting-edge stuff at the time and the cause of many of the reliability problems suffered in testing which persuaded Chris Amon to leave at exactly the wrong moment.

“We stabilised the titanium by shot-peening – firing pellets of silicone at it, which caused it to harden,” explained Forghieri, who was gutted to lose Amon’s renowned testing skills.

Lauda’s Ferrari flat-12, 1975

Grand Prix Photo

Experimentation through the inaugural season with valve angles and sizes helped the engine really start to show its potential, and by the season’s second half it had a clear and decisive advantage even over the special development DFVs used by Jackie Stewart and Lotus, when it was revving up to 12,600rpm at which rate it was delivering 480bhp compared to 450 at 10,500rpm for the special DFVs.

By the end of its life in 1980, the engine was delivering 515bhp at 12,300rpm at a time when a top DFV was good for around 500bhp at 11,200rpm. The relatively gentle power creep in a decade of competition gives one of the clues to the two key limitations of the time: valve springs and ignition. Before the advent of pneumatic valves (introduced by Renault in 1986) engine designers were generally stuck at these sorts of engine speeds by the ability of the valve springs and the ignition pulses to keep up. Pneumatic valves and software-controlled electronic ignition would have allowed more of the 12 cylinder’s potential to have been exploited. But that was some way off in the ’70s.

The Ferrari typically needed around 20kg more fuel in the tank than a DFV car at the start of a race. Its power advantage over the best DFVs varied from year to year but was around 15-30bhp. At the upper end, that advantage was enough to cancel out the initial fuel weight disadvantage (which would lessen anyway through the course of the race). Factor then the aero and centre of gravity advantages and it can be appreciated that Forghieri got about as close as technology of the time allowed in clawing a small advantage for a 12-cylinder over the best V8. It was a remarkable piece of work and was only made obsolete by the innovation of ground effect, as its widely-splayed cylinder banks were in exactly the wrong place for maximum airflow through the sidepod venturis. Those of the DFV were perfectly placed, extending its life for a few years.

By the time of the next normally aspirated formula of 1989, the technologies were there to exploit more of the V12’s potential over the V8. But there came the complicating advent of a perfect compromise between the two: the V10 as introduced by both Renault and Honda for this formula. Forghieri was long gone from Ferrari but the team favoured a V12 for the new formula and it retained this layout for seven seasons – winning races with Nigel Mansell, Gerhard Berger and Jean Alesi and bringing Alain Prost close to the 1990 world title – before bowing to the inevitable and making a V10 in time for Michael Schumacher’s arrival.

Alain Prost at practice at Suzuka in 1990; in the race he’d be cynically taken out by Ayrton Senna

Grand Prix Photo

The V10, using the same cylinder head design as the V12, required 10% less cooling for the same power delivered at lower revs, immediately lapped faster in the mule chassis and was 3.7mph faster down the straight, suggesting the V12 had a fundamental surfeit of moving parts, at least compared to a V10. As John Barnard, who drew up Ferrari’s last V12 and its first V10, summarises in The Perfect Car, Nick Skeens’ 2018 biography of the designer, “Advancing technology had led to ever lighter engines made of exotic alloys, ceramics and titanium, such that a contemporary 10-cylinder engine could now generate as much power as a V12 for less internal friction and weight.”

But Schumacher, upon trying the by-then obsolete Ferrari V12 in testing, felt it was better than the Ford Cosworth HB V8 with which he’d just won the championship at Benetton. “He commented that he could have won the ’95 title easier with the ’95 Ferrari than with the Benetton,” recalled Barnard. “Gerhard Berger and Jean Alesi hadn’t liked the way the internal friction of the V12 meant the revs dropped like a stone when you lifted your foot off the gas, making the back of the car feel loose on corner entry… but Schumacher loved the way it did that. In fast corners he was uniquely able to finesse the rear end drift with rapid microtouches on the accelerator, using the engine braking to create the perfect grip for the bend.”

Even so, the V10 was better – but there was a title-winning V12 in that era: Ayrton Senna won the ’91 championship with a McLaren powered by Honda’s V12 replacement for its V10 before pulling out at the end of that year. Hindsight says it was a retrograde step, but still better than the opposition. It won despite being a V12, not because of.