Lunch With... Freddie Spencer

Arguably America's greatest motorcycle racer, Spencer made plenty of history during his brief Grand Prix career and still has an unusual angle on a rider's psyche

In August 1983 Freddie Spencer became the youngest 500cc world champion, inheriting that accolade from Mike Hailwood (who had succeeded John Surtees). The 22-year-old from America’s Deep South was also Honda’s first king of the premier class, which won him an invitation to Soichiro Honda’s home in Tokyo, where everyone dined on sushi… except ‘Fast’ Freddie, who ate a cheeseburger.

Two years later Spencer made more history when he became the first rider to conquer the 250cc and 500cc world championships in the same year, a feat that has never been equalled. Honda built an NSR500 and an NSR250 specifically to suit his riding technique, while Michelin used him to develop radial tyres. Pre-season and the season itself were brutal.

“We’d be at tracks for six or seven days, doing 200 laps a day, testing 300 tyres, trying to develop two brand-new bikes and radial tyres for both,” says Spencer, who had started racing at the age of four. “And there was no data-logging – we were the telemetry, we were the feedback.”

The idea of winning both championships in 1985 was somewhat irrational. The 500s and 250s always practised and raced on the same days, with sessions and races often back to back, leaving no time to debrief between outings. Spencer had to compartmentalise his feelings for each machine, then communicate them to his engineer, Erv Kanemoto, at the end of each day.

After three of 12 rounds, Spencer narrowly led the 500 series ahead of Yamaha rival Eddie Lawson and was third in the 250 standings. Mugello next. Honda’s NSR500 was a typical 1980s 500cc two-stroke: too much power and not enough grip – “a nasty piece of work”, according to a Honda team-mate. And yet Spencer wrestled the 500 around the Tuscan hillsides in 40-degree heat to beat Lawson’s YZR500 by nine seconds. Afterwards he climbed the podium, sprayed the champagne, but didn’t drink any, then hurried away to the 250 grid. As he departed, his laconic compatriot muttered, “Rather you than me.”

“Most times that year I would at least have a little time, so I could change my undershirt and my leathers and take a little bit of a break between races,” Spencer recalls. “But on that day, I didn’t – they were already letting the 250s out for their sighting lap. The only reason I made it to the grid was because Toni Mang and Carlos Lavado [who won five 250cc world titles between them] sat in the collecting area and waited for me; they were great champions.

“It was never easy adjusting from one bike to the other, and this time when I got on the 250 I was very much exhausted. In that heat guys had been pulling out of the 500 race, so when I stopped on the 250 grid my guys gave me more water. I tried to drink as much as I could. Erv asked me if I was okay. ‘Oh yeah, I’m fine,’ I said. I felt OK, because as a racer you just focus on what you’re doing. But when the race started [push starts in those days] my legs didn’t move; well, they moved but it was like slow motion. I’m pushing and everybody else goes. The first lap I was 19th. I ran them down, picked them off and won the race. Afterwards on the podium, that was the biggest swig of champagne I’ve ever taken. It was a long, long day.”

Mugello was the first of four victory doubles that put Spencer in the history books. But it was also the beginning of the end of his career; something he never talked about until last year, when he published his excellent autobiography Feel: My Story.

“So, I’m sitting there in my motorhome with the two trophies and it was the first time in my entire 19 years of racing that I had this different sense of things,” he adds. “You would consider that Mugello double to be my highest moment, but I asked myself: ‘Is this all there is?”

Spencer secured the 250cc title at Silverstone in early August and the 500 crown the next week at Anderstorp, Sweden, where he hammered Lawson by 22sec. Incredibly, he never won another Grand Prix.

The world’s greatest rider of the era was never the same again because he was burnt out, because he was carrying several problematic injuries and because he had changed, following that spooky moment in his motorhome at Mugello.

His racing career continued for another 10 seasons, in Grands Prix and finally in the US Superbike Championship. Occasionally the old magic shone through, but mostly he struggled with injuries and with a psyche that had somehow been rewired.

In retirement Spencer opened a high-performance riding school at Las Vegas Motor Speedway. But nothing quite worked out. By 2010 he had lost everything: the school went bust and he split with his second wife. He ended up living in a Courtyard Marriott, where he became friends with the hotel staff and helped them with the laundry, while an old friend kept food in his mouth by selling his memorabilia, including his beloved title-winning NSRs.

Quite a downfall, although Spencer doesn’t see it that way. “The thing is it wasn’t a low ebb. That’s the point. Even the day I showed up at that hotel with a backpack and a few hundred dollars I was all good. My mindset was completely different, because there had been a process of getting there, the same process that had got me to Mr Honda’s house, which was always trusting the situation and going with it. People probably thought it was sad, but there was a part of me deep inside that knew this wasn’t the case and that it would lead to more understanding and contentment. Folding towels was exactly where I should have been at that point.”

His full-time Grand Prix career began when Honda unleashed its seminal NS500 triple. Dad sometimes came along for the ride

Spencer family

If this sounds a bit spiritual, it’s because it probably is. When Spencer joined the Continental Circus in 1982 he didn’t fit in. The three previous world champions, who were all still racing, were loud, brash, larger-than-life characters: Barry Sheene, Kenny Roberts and Marco Lucchinelli, who was later convicted of involvement with a Peruvian cocaine-smuggling cartel.

“People thought it was sad, but folding towels is exactly where I should have been at that point”

The boy from the Bible Belt was quiet, humble and polite. While the others guzzled the winner’s champagne, he mostly drank Dr Pepper. And he slept in his motorhome while his beauty-queen girlfriend stayed in hotels. “A lot was made of that… Oh, it’s because of his faith. The main reason was I liked to be in my own thoughts, I was so focused.”

Spencer got the full stereotype treatment from the European press, who christened him ‘Mr Clean’ and wondered about his God-fearing ways. Eventually, even some of his rivals believed the stories.

When Spencer muscled his way to the 1983 world title with an aggressive move on Roberts during the penultimate race, the Californian was apoplectic. And still is. “It was a bit alarming,” says ‘King’ Kenny. “Because here was someone who seemed to think they had divine intervention on their side.”

Roberts’s words echo those of Formula 1 drivers who were suspicious of Ayrton Senna’s alleged relationship with a higher being. Indeed, there are several parallels between Spencer and Senna: the otherworldly talent, the god-like sense of purpose, the shyness mistaken for arrogance and perhaps a faith mistaken for religious belief.

The fact that Spencer was so different from most bike racers certainly got him into some funny situations. There was the Honda team-mate who couldn’t wait to drive him from Circuit Paul Ricard to the Côte d’Azur, hoping to see the youngster blush at the sight of semi-naked sunbathers. And then there was the chauffeur who misunderstood his instructions while driving him from the Dutch Grand Prix to Amsterdam. The chauffeur assumed that the youngster in the back of the car was a normal, red-blooded motorcycle racer, so he delivered him to the city’s red-light district, not the airport. “That was priceless!” laughs Spencer.

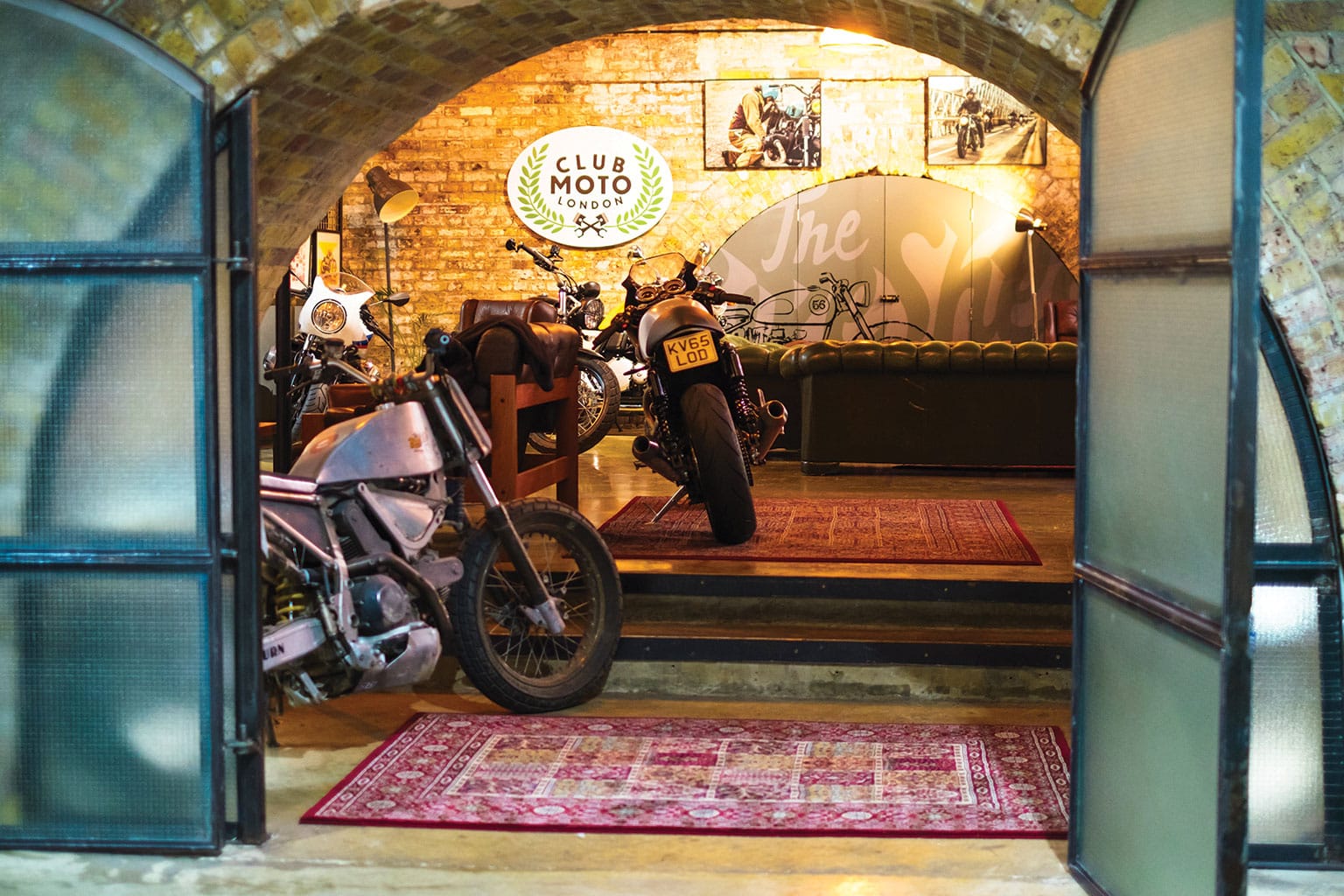

WHILE WE’RE EATING lunch at London’s Bike Shed (a one-stop shop for the brand-new retro biker lifestyle: bar, restaurant, barber, gear shop and lots of cool bikes), we wonder what Senna might have written in his autobiography.

We discuss the famous out-of-body experience during qualifying for the 1988 Monaco Grand Prix. “What happened to Ayrton there was very interesting,” says the 56-year-old, who now lives in London. “Maybe something like a heightened awareness, like there was a stronger connection to something,”

I ask Spencer if he ever experienced anything like that. “I did once, but I never said anything at the time because I didn’t understand. It was at Misano, August 30, 1987; that year’s San Marino Grand Prix. I get taken out by another rider and I’m out cold. It sounds clichéd, but there’s this brightness, this white light and I feel this incredible sense of peace and comfort. Then I can hear my name being called, then all of a sudden there’s Dr Claudio Costa [bike racing’s famously scruffy chief medic] and he’s right in my face. The first thing I notice is the garlic, because he’s just had lunch. He goes, ‘Freddie, where are we?’ And I say, ‘Yugoslavia’…”

Spencer’s petrolhead father gave him his first bike – a Briggs & Stratton minibike, which he rode when he was four

Spencer family

Spencer did meet Senna once, during the 1984 Monaco Grand Prix, where he got to hang out with some of America’s car racing greats. “That couldn’t have been a better weekend: I’m sitting on a balcony over the track, with Carroll Shelby, Phil Hill and Dan Gurney.”

Spencer dabbled in car racing during the late 1980s and became friends with Niki Lauda, Mario Andretti, John Surtees and others. There was talk of a test with the Williams-Honda Formula 1 team and he was fast enough in an Indy Lights car to get an offer from IndyCar team owner Chip Ganassi.

“But I went back to bikes. The margin of error is so much narrower, so your precision is honed to a higher level. Plus, you really can use your body and your technique to change your lines and so on.”

Spencer was sublime on a motorcycle. His three world titles and 27 Grand Prix victories don’t do justice to the quality of his talent, because he was one of that rare breed of racer that can magic extra performance from a motorcycle, by moulding his technique around the machine. Others on that list include Surtees, Roberts, Spencer, Australian Casey Stoner, current MotoGP king Marc Márquez and maybe one or two others.

In the late 1970s Roberts was the first GP rider to slide the rear tyre to gain an advantage over his rivals. Spencer was the first to slide the front, a much riskier trick.

Another Honda engineer who worked with Spencer remembers being amazed by this ability to do something that most other riders wouldn’t even contemplate. “Freddie really knew how to use the front tyre,” says Stuart Shenton. “Normally in those days, a set of front brake pads would go a race distance, but with Freddie they would do four or five races. He was running so hard into turns to the point where he was drifting and sliding the front.”

Spencer introduced this technique while riding Honda’s beautifully user-friendly NS500, the bike that carried him to the 1983 championship. “I liked the NS because I always knew what it was going to do. I could get ahead of it and catch it. If the front went real fast, I’d get on the throttle to get some weight off the front, then the rear would slide, so I’d just modulate between the two.”

This was man and machine in perfect harmony – an awe-inspiring sight that had some paddock people wondering if this unusual racer really did have some kind of supernatural assistance. While the press called him Mr Clean, fans nicknamed him ET: the Extra-Terrestrial.

The truth, of course, was slightly different. “People said I was a natural, but by the time I was 13-years old I was racing 40 weekends a year in all categories.” And he had been riding bikes since he was three. His father was also a petrolhead – mostly karts and drag racing – who hid young Freddie in the seat well of his Pontiac GTO drag car, so he could enjoy the thrill of the strip.

“I’d be out in the rain, using the wet leaves and the slick Louisiana clay, trying to learn to change direction at any lean angle”

In those days Spencer spent most of his time in the backyard, riding a succession of minibikes, honing his skills, day after day. “I’d be out in the rain, using the wet leaves and the slick Louisiana clay, trying to learn to change direction at any lean angle. When it was dry I’d carry more speed, throw it in on its side, snap it around and pop it up. I’d use the front brake too because the front brake controls the gyroscopic effect of the front wheel.

“I could judge when the bike would stop sliding. Right at the apex I’d pick it up, so the bike is pivoting around the front tyre and the front’s not pushing any more, then I could just drift turn. Think how important that is in a 130mph sweeper – when you’ve got the bike on its side and you know exactly where it’s going to end up. When I was on top of my game I could go through that 130mph corner on a four-inch-wide line, lap after lap.”

Spencer’s genius made him a very rich man, very quickly. He made money and he spent it too. At the time of his first world championship success he was dating Miss Louisiana. In 1985, when he was going for the 250/500 double, she was getting herself ready for the Miss USA beauty pageant. He remembers them returning from races in Europe, taking Concorde from London to New York, then a Learjet to his hometown of Shreveport, where the mayor announced a Freddie Spencer Day.

He knew what he liked and was happy to spend his hard-won gains to obtain it. When he couldn’t find a Mercedes car that suited his tastes at the US importer, he had a German-only model shipped over. And he bought the local Honda dealership.

By rights, he should now be comfortably retired on a thousand-acre ranch, playing golf and mucking about on dirt bikes. But he insists he doesn’t miss any of those things.

“Flying in a Learjet was great, and it was convenient. I’m happy I had those experiences, but all that stuff is fleeting. I’m now more thankful than I ever was for having had those experiences and I really, truly mean that. My appreciation for standing on the podium at Mugello and all those other places is much greater today because of everything that’s happened since then.”

His purchase of JW Gorman’s Power Cycle Honda dealership in Texas Avenue, Shreveport, had an important significance for Spencer. When he was six years old he had visited the shop with his father. On the wall he spotted a faded black-and-white photo of Mr Gorman shaking hands with a Japanese gentleman, Honda-san himself. This is what set him on the path to signing for Honda in 1980, even after he had witnessed the company’s disastrous return to Grand Prix racing with its oval-piston NR500 four-stroke in the 1979 British Grand Prix at Silverstone.

His first asphalt races were on 125s and 250s, but by the time he was 14 he was racing a 180mph Yamaha TZ750, the fastest bike in the world

Spencer family

“I was sat on my sofa at home, watching the broadcast. I can still see the Honda garage, with [NR engine-designer Soichiro] Irimajiri standing there. It was a disaster. When I signed for Honda, the downsides were much greater than the upsides. Yamaha was the big racing factory at the time and they were offering me a deal. Kawasaki too, and they’d just won the 250 and 350 world championships. At that time Honda was the non-racing factory and all they had for me was a contract to be their fourth rider on their US Superbike programme. That was all, but I just knew that’s where I should be.”

Spencer and Honda became synonymous. When he fronted the company’s first foray into Grand Prix racing with two-stroke machinery in 1982, Honda established its new racing arm, the Honda Racing Corporation, which still looks after its MotoGP operation, with Márquez, Cal Crutchlow and others.

Everything that HRC has achieved since then is built on the foundations laid in those early years when blue-sky thinking and experimentation were still very much the thing. The year after Spencer won Honda’s first 500 world title, HRC sent him racing with an ‘upside-down’ NSR500, with the fuel tank beneath the engine and the expansion-chamber exhausts curving over the top. The idea was to lower the centre of gravity, as is the way in cars.

It didn’t take long for Spencer and HRC to realise that this was a big mistake. A motorcycle needs a higher centre of gravity to help it pitch into and out of corners, to transfer load and grip between the front and rear tyres. Also, mechanics quickly got fed up barbecuing their fingers on the exhausts while changing spark plugs. As Honda-san famously said, “Success represents one per cent of your work, which results only from the 99 per cent that is called failure. Success can be achieved only through repeated failure and introspection.”

More than four decades later Spencer still works for Honda, now and again. He’s a busy man, earning a living doing TV commentary, riding at classic meetings, like the Goodwood Revival, and attending all kinds of promo events.

The day we lunch together he has just returned from Canada, where he was the star turn at the Toronto Spring Motorcycle Show. Before that he was at Daytona, launching a 40th anniversary edition of his Arai helmet design and inducting an old racing friend into the American Motorcyclist Association’s Hall of Fame. The day after we meet he’s off to MotorLand Aragon to commentate for Eurosport on the Spanish round of the World Superbike Championship. There are plenty of ex-racers on TV duty these days, but few with such an unusual take on the racer’s condition as ‘Fast’ Freddie.