That first win at Le Mans in the Testa Rossa was shared with Olivier Gendebien, with whom he also won in 1961 and 1962. “It was something special,” says Hill, “that feeling when you know you can win, when the sun shines after the rain and there’s no tension any more. We were a good team, we had faith in each other. Some team-mates are so concerned about their own status and they lead you down the garden path. But we had faith in each other, Gendebien and I, and we’d never kid ourselves, we were always open with each other. I liked Peter Collins a lot as well. We got on real good, and Mike Hawthorn too. They both liked to party, especially Mike.”

Promotion to the grand prix team followed a run in Joachim Bonnier’s Maserati 250F at Reims. Joining the Scuderia’s F1 squad for the German GP, Hill was quick in the Ferrari 156 straightaway but it was by no means all sweetness and success. Enzo Ferrari ran the team with an enormous amount of discipline and there was a huge level of internal politics. At Monza that same year he was asked to slow down, not an order a young racing driver likes to receive. The new boy was about to be summoned by the headmaster.

“I led the first few laps, then a tyre went down and I had to make a stop. Later I got the lead back and Tavoni came out in front of the pits and signalled me to slow down. I was a new boy, I wasn’t supposed to be up at the front. He was on his knees at the side of the track and the message was clear, the board reading HAW HILL, meaning Hawthorn was to be allowed to pass me and take second behind Brooks in the Vanwall. Anyhow, I started messing with the ignition switch, popping and banging past the grandstands for a few laps, so it looked like I had a problem and Hawthorn just went by. The Brits always seem to leave that story out when they talk about the ’58 season! It was kinda silly really, and the same thing happened in Casablanca, that time Enzo Ferrari and Tavoni had planned for Hawthorn to finish ahead of me. There was less than a second between us at the finish. But he was, you know, the team leader, and he had disc brakes on the car by then, you know.”

Compare this with recent machinations to keep Schumacher ahead of Barrichello and the clumsiness of that most public debacle just yards from the line in Austria. But it was ever thus at Ferrari, and Hill went through the school of hard knocks before winning the championship for the Italians four years after joining the team.

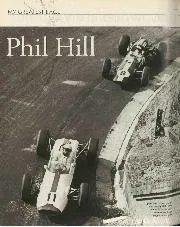

Hill at the Nürburgring ahead of the 1961 German GP

Grand Prix Photo

The title came in 1961, at Monza, Phil having already won at Spa. Both fast circuits, demanding skill and bravery from the American in the famous shark-nose Ferrari 156.

“I don’t know if I loved those tracks, or it was just that I wasn’t afraid of them,” he says. “People spoke badly about Spa and Monza: they were afraid of being hurt bad I guess.

And the Nürburgring, I liked that, the car flew so beautifully, landed so beautifully, and lap by lap we went faster and faster. We got the lap record, first time under nine minutes. Incredible, yeah.”

Hill leads Clark at Zandvoort in 1961

Getty Images

But the victory at Monza was an emotional rollercoaster, a storm inside his head, the news of Wolfgang von Trips’ death during that race thrusting a dagger through the celebrations for his world championship.

“It was blighted alright. Of course it was. We didn’t know how bad the crash had been, you know. I mean in those days there were so many like that. Then we got the news and part of me wanted to be so happy for the championship and part of me was so full of grief. I’d gotten to a point by then when I was more sensitive to things like that and then the press asked me all this crazy stuff about inheriting the championship and all of that. It was ridiculous. I was in cold turkey. It wasn’t pleasant at the time I tell you.”