1975 Austrian Grand Prix race report

— A washout Osterreichring, Knittelfeld, August 17th The entry list for the Austrian Grand Prix was very full, almost to the point of overflowing as regards drivers, but after the…

Roger Penske arrives at the Royal Automobile Club in London straight from the airport. He is here for a dinner to celebrate his remarkable career. At 5am tomorrow he flies to Germany for a business meeting, then back to America. A couple of days earlier he turned 82 but, as our interview reveals, he shows no sign of slowing down.

Penske’s legend is undoubtedly strongest at Indianapolis, especially at the Indy 500. Team Penske is the most successful team ever to compete at the event, having scored 17 victories since first entering in 1969. His name has become synonymous with America’s greatest racing event.

“It was pretty special when my dad first took me to the Indy 500 as a 14-year-old,” says Penske. “I’d listen to the race on the radio before that and was already bitten by the car bug. I remember we didn’t have very good seats that first time: we could hardly see the cars on track, they were the big, old wooden grandstands back then.

“I remember Lee Wallard won that race [1951] and I was just infected by the race. I went to every single Indy 500 since, [aside from the four-year sabbatical Penske took from 1996-2000 due to the split between Champ Car and Indy Racing League]. For 46 years we’ve competed at Indy and we’ve had 17 wins and it’s just a very special, magical place.

“It’s the greatest automobile event in the world, they had over 300,000 people there last year and it’s an amazing oval, 2.5-miles long, and it brings the greatest drivers. I don’t think there’s a Formula 1 or racing driver anywhere in the world who wouldn’t want their face on that Borg-Warner Trophy alongside the likes of Graham Hill, Jackie Stewart, Jack Brabham and so many others who have been successful there.

“There are three pillars to being successful in motor racing, one is building your brand and the Indy 500 has certainly built our brand. We operate in five countries and it’s amazing. Indy also pushed technology. I remember when we had to look at stopwatches to work out which cars were fast, and now you can go online and see every driver make every move in real-time. The last aspect is the people, and you can see the team we’ve built around Indy. Originally we went to Indy with seven people and when we go back for 2019 we will have almost 700 years of experience collectively in our garage.”

Penske’s only real lapse at Indy was when he pulled his cars for the four years when Champ Car and the Indy Racing League split. But does he regret that politically enforced sabbatical?

“We had our differences with the USAC [United States Auto Club] at the time and didn’t agree with how they wanted to run IndyCar,” Penske adds. “They had other interests such as stock cars and midgets and championship cars and Indy wasn’t the focus and we just couldn’t get together with them as a group. Probably it [the sabbatical] wasn’t a good idea as I reflect back, but we left the series and then came back in 2001 and had victories – three in a row. But I do look back and think it was perhaps not a good idea to have that hiatus.”

Mark Donohue was a pivotal driver during Team Penske’s formative stages. The likeable New Jerseyman competed for the team through a plethora of different formulae – from IndyCar to Formula 1, via Can-Am – throughout the 1960s and early ’70s.

Donohue lost his life after suffering a brain hemorrhage following a heavy accident during practice for the 1975 Austrian Grand Prix, when his Penske-run March 751 suffered a tyre failure and pitched him into the catch fencing.

“Mark was an engineer from Brown University in the north-east and I saw him racing sports cars at Lime Rock Park a few times,” says Penske. “A friend of mine at the time said ‘You gotta watch this guy’, so we got together and formed a race team and he was like a brother to me.

“Mark’s engineering background was a huge advantage for us, perhaps the unfair advantage if you like. We were competing in road racing, NASCAR, the International Race of Champions and Formula 1, so there were a lot of things involved. But Mark was the guy who swept the workshop floor at night, drove the truck if he had to and worked on the cars and I think that common thread of having a flat organisation and a personal commitment is really the foundation to our company today and the 66,000 people we employ.

“We were many nights working all night long when we had to get the cars ready and Mark would work late, sleep a few hours and then be up early to drive the truck. He was all-in, passionate about motor racing and he wanted to be a winner and set a standard, perhaps a different standard to what we’d seen in the past.”

One of Donohue’s standout achievements was setting a new closed-course speed record when he achieved 221mph at Talladega Speedway aboard the Penske-developed 1500bhp Porsche 917-30 Can-Am car (see page 104). That record came just days before his ultimately fatal crash at the Österreichring.

“I wasn’t actually there [in Austria] that day,” says Penske, “but it had a big impact on me personally. As I said, Mark was like a brother and he was the heart and soul of the team for so long. It was a big decision afterwards like ‘what do we do?’, but we knew Mark would have said ‘keep going’ so that’s what we did with the support of his family, but it was a tragic loss. Mark was really the catalyst and cornerstone of our success for so long.”

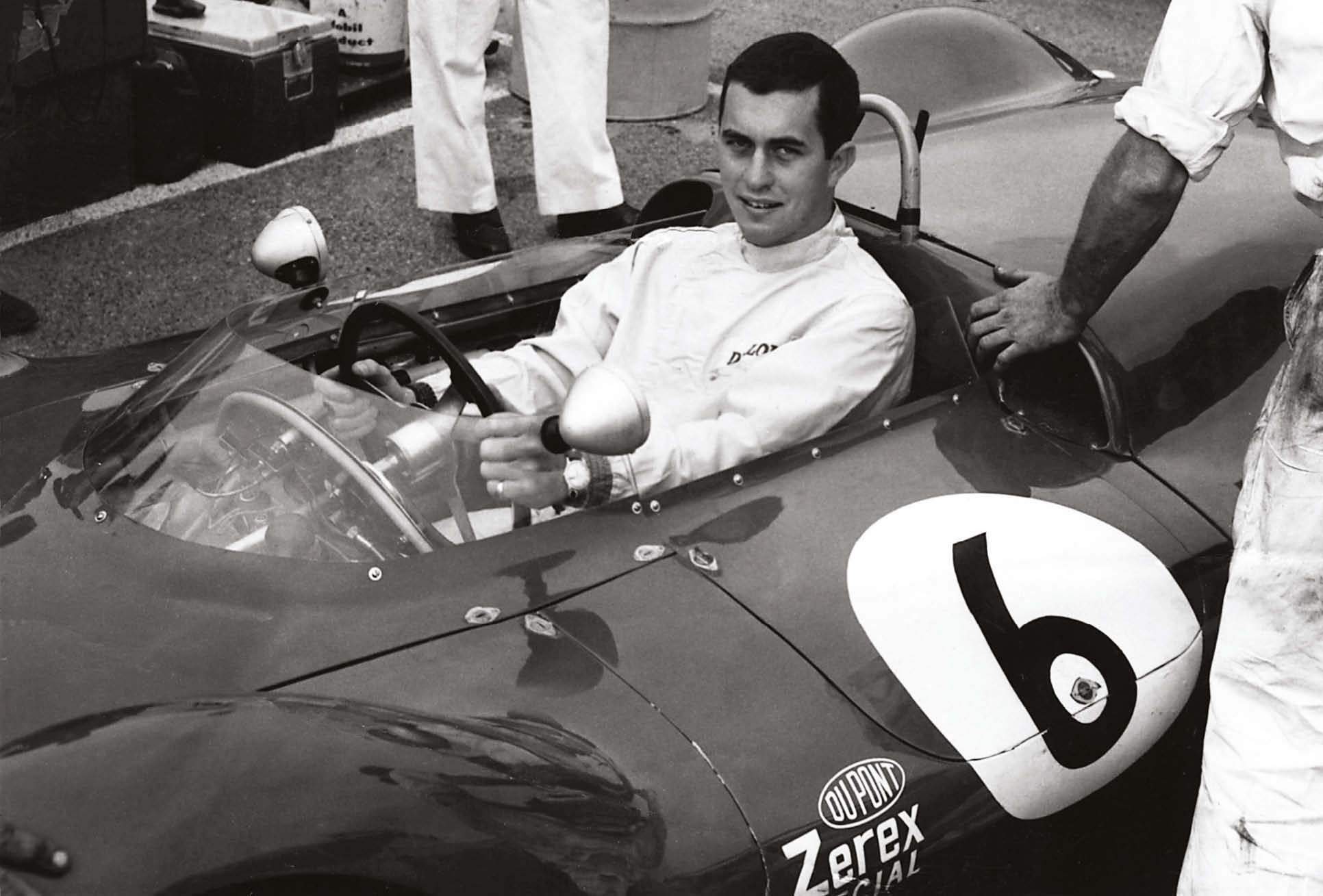

Helio Castroneves, left, scored an Indy 500 hat-trick for Penske, winning in 2001, ’02 and ’09. Above, Penske at the wheel of the Zerex Special

Aside from Donohue’s technical nous, Penske always chased what he terms as “the unfair advantage”, small often innovative engineering solutions designed to find those extra tenths of a second.

One of his early innovations was acid-dipping the chassis of his Trans-Am cars, which would remove the additional layers of paint, adhesives and sound-deadening from a stock chassis in order to make it lighter than the competition.

“We had a body in white, which was your standard unibody-type construction and we found an acid tank in California where we could dip the chassis in and it would take off about 50-60-70lbs by the time it came out. The first few times we tried it the chassis came out more like a sock, but eventually we got the right ingredients in there and we regularly shaved off 50-60lbs.

“Then of course the car roof would have a lot of oil can in it [a term when thin metal visibly flexes, like squeezing an oil can], so we’d put a leather cover over it – which wasn’t unusual then – so you couldn’t see the oil can and we told everybody the cover was to make the car faster, like a golf ball. We had some fun with that one.

“Probably the most interesting unfair advantage was when we built a 30-foot fuelling rig and put the 30-gallon drum on top and we could fuel in about three seconds, and everybody else was taking 8-10sec. That lasted for about two races before we got told to tear it down and take it home.”

“Mark Donohue was the catalyst and cornerstone of our success for so long”

A footnote of Penske’s career is the fact that he, almost unknowingly, inspired Bruce McLaren to begin his eponymous business by having a hand in the first car McLaren ever built – through his Zerex Special.

Penske: “That car has an interesting history. It was originally an F1 Cooper [T53] that was damaged at Watkins Glen with Walt Hansgen driving and I bought the chassis. Then Jack Brabham came to Indy with a 2.7-litre Cosworth engine, so we took the Cosworth and put it into the F1 chassis and we had a guy in Philadelphia who built us a sportscar body and I sat in the middle of it. I won the Riverside [Formula Libre] race and the Laguna Seca race and then of course people started saying I couldn’t sit in the centre. I questioned that there were two-litre Coopers that were running, but we changed it [into a two-seater].

“Bruce McLaren eventually bought it from me and fitted a Buick Oldsmobile 3.5-litre V8 and changed the chassis and that became the first car McLaren ever made. Bruce and I were great friends because of the Cooper relationship [Bruce raced for Cooper in F1 from 1958-’65 before founding McLaren] and that was a great car, very fast. I remember running it in one bank holiday meet in August and I could run the [softer] wet Dunlop tyres in the dry and won. The scrutineers were all over us that day and I remember Graham Hill came over and helped us pass the inspection after the race.”

During the early 1970s Penske began to seriously investigate a Formula 1 entry, entering two rounds in 1971 with a hired McLaren-Ford before committing to build its own grand prix racer – the PC1 for 1974. It did two rounds with Donohue that year before signing Briton John Watson to race a second car for the full 1975 season. That was the start of a three-year F1 campaign, which would bring a single win – Watson in Austria 1976. Penske remains the only American team to ever win a world championship grand prix.

“We bought Graham McRae’s workshop down in Poole, Dorset in 1973/74 and our first F1 car, the PC1, was designed by Geoff Ferris and it was a start for us,” recalls Penske. “F1 was a cottage industry in Britain, with people from New Zealand, Australia and all over the world coming here to work and the technology was here, which we didn’t have in the US. Moving here to run the F1 programme made sense. F1 was something that was important for our brand, but when we got to Indianapolis and saw the success we could have with Penske-built cars, even though they came from the UK, it was amazing. With the NASCAR and stuff we were doing we ultimately opted to stay in the US, but in 1976 we finished fifth in the F1 World Championship.

“We’ve looked at F1 since, and I know Gene Haas [Haas F1 owner] well because of the racing relationship we have in NASCAR. As I see it, the commitment is scaled-up with F1 with the staff and equipment required and I was not going to be able to run my business and operate in the US while trying to take on the factory teams here [UK]. The cost levels are significant and we wouldn’t benefit from the notoriety and brand building F1 gives you.

“There was a business thought that F1 would be overload. But when the rules change [in 2021] it will attract new people, but I’m not sure on the state of the sport right now. I’d love to come in with an American team and American drivers, but I don’t think that’s the next chapter of my career at my age. You have to run the whole season and we just wouldn’t be competitive. The technology and team you need. I don’t think F1 is on the shelf for us.”

“I even said ‘Let’s pull an old Audi LMP1 out and run that at Le Mans’, but it was a big step”

It wasn’t just single-seaters and stock cars that Penske prospered in either, the team has also been successful at endurance racing showpieces such as the Daytona 24 Hours and Le Mans. Penske still harbours ambitions to win in France.

Penske first won at Daytona with a Lola T70 in 1969 and more recently operates the factory Acura Dpi prototype programme. Around that, Penske’s work on Porsches in Can-Am sparked a relationship with the Stuttgart brand, which would lead to Penske running the firm’s RS Spyder LMP2 machines in the American Le Mans Series in 2006 and giving Porsche its first victory in the Sebring 12 Hours since 1988 when it won with Timo Bernhard, Romain Dumas and Emmanuel Collard in 2008 – beating the all-conquering Audi LMP1 crews.

However, Penske still harbours the ambition to win at Le Mans. He says: “I raced at Le Mans myself with Pedro Rodríguez [in 1963] and we’d love to go to Le Mans as a team. It’s the one trophy we’re missing really. We’d probably go with a GT car the year before to understand the nuances of racing there. You can see it and feel it and experience it because you can only do that by being there competing for a week.

“We beat the Audis in America, but Audi had great team like Joest doing a good job. I even once said ‘let’s pull one of the old Audis out and run that’ but with the diesel technology and things like the hybrid systems there was a lot to do. It’s a big step and we had to be sure it wouldn’t impact our core business. Hopefully there will be a point in the future where we can do it with the rules looking at supercars and such as the future, and we can find a budget to go there. Getting a win at Le Mans is certainly on my want to do list.”