In time the Porsche was developed into one of the most dramatic and efficient racing cars of all time. Sadly for him, Donohue missed most of the 1972 Can-Am season after suffering serious injuries in a testing accident at Road Atlanta, caused by the loss of the rear bodywork. Ever the team man, he went to the races, hobbling on crutches, helping replacement driver George Follmer to the championship.

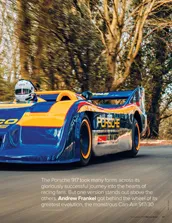

The following year he walked the Can-Am Championship, winning six of the eight races, now in the 917/30. More than 30 years on the figures still astound: 1100bhp at 7800rpm (on normal ‘race’ boost) and 810lb-ft of torque at 6400rpm. Donohue adored what he called “the era of knife-fight rules”. In pre-season testing at Paul Ricard he exceeded 240mph on the Mistral straight.

In the car’s final race, at Riverside, Mark established himself in the lead, as usual, and then started to play with the cockpit-adjustable roll-bar. “I turned it up to oversteer and I had a great time, sliding all over the place, knowing I could rebalance the car at any time — and that this was my last race.” He made the announcement afterwards.

For all his successes, Donohue never quite appreciated how good he was, and his friend Posey was at a loss to understand why. “Mark always attributed it more to his engineering skill and hard work than pure driving ability, but he was certainly as fast a driver as I ever competed against.”

Whatever, Donohue prepared for a new life as president of Penske Racing, and his decision had nothing to do with the risks then so prevalent in the sport. “I can’t say I was ever personally concerned about my own safety in the car,” he wrote in his autobiography, “perhaps because I’m something of a fatalist — I figure no two accidents are ever quite the same and, even if you’re prepared for every contingency, something else is going to get you some day.”

After a year out Mark found he missed driving, and when Penske embarked, for the first time, on a full F1 programme, he decided this was a challenge he couldn’t resist.

“Problem was, Mark had retired too early,” said Mario Andretti. “He was only 36 and it wasn’t out of his system. At the time I said he’d never be happy with himself. On the other hand, he then broke what to me is a golden rule: never come back.”

The odds against success were high, it must be said, for in 1975 Penske was running its own car, in Europe, on unfamiliar circuits, and Donohue was the only driver. By mid-season the recalcitrant PC1 had been ditched, and the team moved on to a March.

“He felt a little out of it in Europe, I think,” said Andretti. “On race morning in Austria — the day it happened — we were chatting and he said, ‘You’re doing F1 and Indycars, so you’re going home tonight. I have to stay here…”

During the warm-up at the Osterreichring, Donohue had a front-tyre failure as he pointed the March into the Hella-Licht Kurve, a flat-out right-hander at the top of the hill beyond the pit straight. He went over the guardrail and struck lead-pipe advertising hoardings.

Initially it seemed like a miraculous escape. Although Mark was complaining of head pains, I saw him on a stretcher in the Penske pit and he was speaking to members of the team. Donohue was then flown by helicopter to a hospital in Graz, and perhaps this — three years before Professor Sid Watkins arrived to transform medical practice in motor racing — was crucial, for subjecting someone with a head injury to altitude is not the best thing.

Later in the day we learned that Mark had a fractured skull and was deeply unconscious. On the Tuesday he died.

Andretti remembered him well. “Mark was a very technical driver, a guy ahead of his time, the first really to understand the depths of aerodynamics. He wasn’t necessarily the fastest guy, but I guarantee you he usually had the best set-up car. A thoroughly polished individual, a very correct driver, the ultimate professional. But when you got to know him, you saw there was also a ‘go to hell’ side of him — he liked whisky, liked to let his hair down sometimes. Good guy, good guy.”