club news, October 1930

aid/lewd SOUTH-WEST LONDON M.C. Mr. R.. E. Percival is now hon. secretary and all communications and enquiries should be addressed to him at 83, Bramfield Road, S.W.11.. This club, Which…

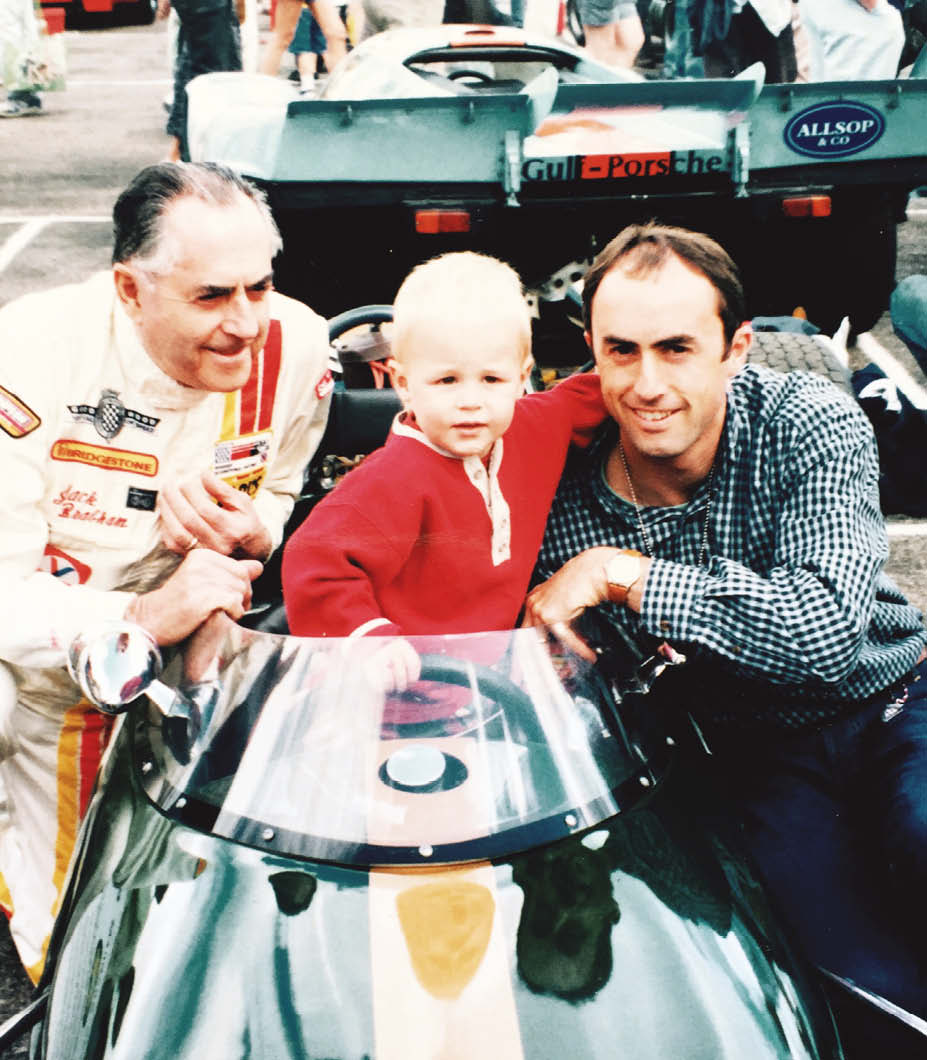

Their name is rich in racing pedigree. David, 53, is the youngest racing son of triple world champion Jack Brabham; his own single-seater hopes stalled after winning the 1989 British F3 title, but a long, successful sports car career included one outright victory and two further class wins at Le Mans. His 24-year-old son Sam’s ambitions have been on hold for a couple of years, following early signs of promise in Formula Ford, but he hopes to be back on track soon. Here, father and son talk about what it was like growing up with the Brabham name and the changing racing scene.

David: My upbringing was different from Sam’s. I was born in Wimbledon but when Dad retired, in late 1970, I was four and a half and we shipped out to Sydney. At 13, I was sent to an agricultural boarding school, as the family groomed me to run our farm in Wagga Wagga. It was 4500 acres, just outside Wagga. You could do anything you wanted and I loved being outdoors. But it wasn’t easy. We had droughts and floods.

Whatever I was driving around the farm, I’d be flat out and sideways. I didn’t realise it at the time, but this was race training, giving me car control, feel and quick reactions as I balanced a car or truck.

I didn’t buy a kart until I was 17, going halves on a second-hand chassis with a pal and paying for everything through the money I made on the farm. Once I started in Formula Ford, Dad paid for a car and after that I was lucky enough to get free drives.

It was the opposite for Sam. He was at boarding school and about 14 when he first expressed interest in getting a kart. I wasn’t sure how serious he was; did he really want to follow in the family footsteps, or did he just want to mess about?

At the same time, I was in the middle of an expensive court case [to protect the rights to the Brabham name], and I didn’t have funds to pay for his racing. And even in karting you need a lot of money today.

That was painful. People would assume that a Brabham would have money behind them, but no. I could see he wanted to get out there, but I had to focus on the long-term legacy – the next chapter of Brabham.

So the early phase of his career was sacrificed, in a sense. And to be brutally honest, karts didn’t suit his style – and I told him as much. The way he’d enter a corner and rotate the kart wasn’t the best technique; it was better suited to a car.

When he did get his drive in Formula Ford, he qualified seventh for his first race at Donington Park yet was still learning the track, as he’d not had a test day. His sector times at Craner Curves, McLeans and Coppice were the fastest in the race. Afterwards, Nick Tandy, who owned the JTR race team running Sam, said, “Are you sure he’s not driven a racing car before? That’s not what we expected!”

As an active racer, Lisa [David’s wife] and I had to make some tough calls about Sam coming to my races. I remember when we made him stay at school for a cross-country running race and he desperately wanted to come and watch me at Le Mans, with Aston Martin. Lisa and I put our foot down, saying, “You’ve made a commitment; you have to keep it.” He was pretty cross…

I didn’t plan to enter F1 the way I did. I got a call from Middlebridge Racing, the F3000 team for whom I’d signed in 1990 after winning the previous year’s British F3 championship, and they told me they were concentrating on F1. They’d acquired control of Brabham and basically said, “You either race with us in F1 or find a new home” – not something I fancied at that stage.

So I took the drive, not knowing that the show was imploding. My F1 dream was quickly shattered. There was no money for engines; no money for anything. It was a disaster. All my momentum after winning F3 just stopped.

For Sam and drivers of his generation, you have to work a lot harder to secure sponsorship. That’s another reason why I set about rebuilding the Brabham brand, to develop opportunities.

Brabham will return to racing: we aim to take the BT62, the first car from my own company Brabham Automotive, to Le Mans in 2021. The first deliveries of the BT62 track car will be in July, and I’m proud of what our team has achieved in such a short space of time. Sam can be a part of that.

If there was one car from my career that I could fix for Sam to drive, it would probably be the Jaguar XJ-R14. It was a magic thing.

Dad was a private man, but when he gave you advice, it went right through you. Once, he tapped his fingers on his head, and said, “David, it’s all in the head.” It’s advice I passed on to Sam: you have to set your goals, make things happen. No one can do it but you.

Sam: When I was growing up, Jack was just my granddad, no different to anyone else’s granddad. That’s why Ayrton Senna was someone I looked up to.

I first became aware of the significance of my family name after I went to boarding school. My art teacher – obviously a racing fan – wrote ‘Jack’ on my exercise book and was terribly apologetic once he realised his mistake. Then it dawned on me and I started to look into it and ask questions at home.

Since Jack passed away I haven’t been out to Australia much. Then, last October, Dad and I did a road trip to Oz.

We had a BT62 test arranged at Phillip Island and Dad was racing at Bathurst, as a guest of Toyota, and there was a gap of about a week and a half between – and we had a car on loan.

Dad hadn’t been back to the farm for about 25 years –and I’d never visited. Seeing it put all the stories into perspective. According to Dad, some of the wallpaper was still the same as when he grew up there!

In 2009 the whole family went to watch Dad compete at Le Mans. He’d told me that it’s rare a driver has a good chance to win Le Mans outright, so seeing the race unfold, appreciating the elements that it takes to win and feeling the emotion at the end was overwhelming.

At the time of the court case around the Brabham name I didn’t really understand what was going on. As I got older, Dad told me it would give me a platform to do more. Now I understand what he was getting at.Seeing a professional athlete at home is probably what steered me to study sports science at university. Dad would be working out in the gym and that stuck with me. As did the mental side of things, which I came to appreciate is so important in the car. So during my studies I related a lot of the learning to motor sport, even though none of my tutors touched on it.

Dad taught me about visualisation. When I was young, I might have been able to picture a clear lap but my clarity wasn’t great. He helped me to speed everything up on the laps, visualise clipping each apex and even work on start strategy.

“The BT62 is insane – by far the quickest thing I’ve driven. I want to race it”

To be honest, finding sponsorship was much more of a challenge than the physical and mental side of things. In sponsorship pitches, sometimes those who were familiar with our name assumed we’d have money and wonder why we were knocking at their door. But that only makes you fight harder and appreciate everything you achieve.

The hand-to-mouth way of racing eventually caught up with me in Formula Ford, when I crashed at Oulton Park [in 2014]. A rear suspension arm collapsed, sending the car onto the grass, and then it rolled. It all happened so quickly. After that, unfortunately, the money was exhausted.

Since then, I’ve been making a living doing customer demonstration drives, with car manufacturers, and private coaching.

There was also a spell working with Wirth Research, helping Honda develop its IndyCar. Justin Wilson was one of the drivers and I worked with him on the project to develop the car for road courses. It was tragic to see him lose his life in a freak accident.

I haven’t given up on my F1 dream, but the most realistic goal is to be a professional, paid driver within five years. I had a run in the Porsche Carrera Cup series and went well. I reckon we’ve got three-quarters of the budget to race in whichever series we choose, with time to raise the final chunk.

Brabham Automotive is exciting. I’ve seen how Dad’s fought to keep the heritage going, and to have the family involved in that would be fantastic. His car, the BT62, is insane, by far the quickest thing I’ve ever driven. It made an LMP3 car feel slow. My ambition is not just to have my family name on the badge – I want to race it.

Sometimes I’m asked whether drivers could be replaced by a computer, but I don’t believe we’ll ever be redundant. People want to cheer on heroes and hopefully I can give them another Brabham to support.

Interview by James Mills