Through my 20-odd years as a Grand Prix journalist, I have been repeatedly surprised by the drivers’ lack of childhood enthusiasm for motor racing. Most, indeed, seem almost to have stumbled upon it. “I had nothing to do one weekend,” James Hunt would say, “went to Brands Hatch with some friends – and was hooked.”

Unusual, too, is any interest in the sport’s history, or, to put it another way, in anything that happened before their own involvement began. Chris Amon and John Watson are exceptions to the rule. “In some ways, it’s a disadvantage,” said Amon, who loved it from the cradle. “I started F1 when I was 19, and I was overawed by Clark, Brabham, Gurney and so on these people had been gods to me…”

Racing journalists, though, fall readily into this camp. ‘Those who can, do; those who can’t, write about it,’ may be a cliché, but it sums up the specialist press, most of whom fell in love with racing when they were kids.

I can remember exactly how it happened with me. From my earliest recollections, I had been fascinated by cars and speed, but it stirred into the beginnings of a passion one evening in April 1954, when a clip of the Pau Grand Prix was shown on Sportsview, a BBC programme of the time.

Actually, it was more than a clip, as I recall, perhaps running to five minutes. And in that time the narrator captured my imagination, describing this cat-and-mouse battle between two very disparate Frenchmen, Maurice Trintignant and Jean Behra.

It was a most unusual race for the time, in that Ferrari – represented by Trintignant – did not win. After building up a lead, the red car was gradually hauled in by Behra, number one driver for Gordini, the perennially under-financed little French team. “Trintignant strives to close the gap in the last few laps,” the commentator noted, “but it’s Behra’s race…” I can hear those words as if it were yesterday.

Behra’s victory, he assured us, was the triumph of a better driver over abetter car. The final pictures were scenes after the race, and right there I was enslaved. They might have been from different planets, Trintignant correct and phlegmatic, a dapper man whose driving mirrored his appearance, Behra also small, but stocky, apparently with charisma to throw away.

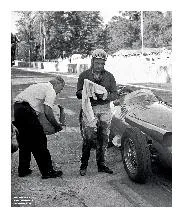

So here I was, just after my eighth birthday, and facing a sea change in my life. For the next five years Jean Behra, his chequered helmet, his victories, his innumerable accidents, became my world, and when he died, at Avus in 1959, I came to understood for the first time what was meant by grief. I never spoke to my idol although my autograph book bears the signatures of Fangio, Moss, Hawthorn, Castellotti et al, I was always too over-awed to ask Jean – but nearly 40 years on a photograph of him retains pride of place on my office wall.

Why he was of surpassing importance to me, I cannot tell you, because I don’t have the answer. It didn’t matter to me that there were greater drivers, that he was never World Champion, nor even – somehow – won a Grande Epreuve; what appealed primarily, I suppose, was his utter fearlessness. Fangio was right when he described him as “too brave”, but this can never be a fault in a childhood hero.

Those of us in thrall to Grand Prix racing support certain drivers throughout our lives, and if favourites of mine have included such as Prost, an elegant stylist who made it look easy, more usually I have been more drawn to the derring-do brigade, to Rindt, Peterson and, above all, Gilles Villeneuve.

Among the current drivers, Alesi is one I root for, and Jabby Crombac is not surprised: “But of course Alesi is the Jean Behra of today! Lovely guy, looks the part, tremendous guts, too emotional, drives with his heart…”

Denis Jenkinson was another who thought highly of Behra, and down the years we sank many a cognac as we talked of him. “More than anything else,” he said, “what I liked about him was his pure love of racing cars.

He was a good mechanic in his own right, but he never fettled cars for the fun of it: the only thing that mattered was making them faster. They loved him at Maserati, because he was happy to ‘live above the shop.’ “Then, the ultimate accolade from DSJ: “There was no bullshit about Jean. He was a racer’s racer.”

In the 1950s Jenks was frequently in Modena, where Behra was an almost permanent resident at the Albergo Reale. For ‘Jeannot’, a day without some time in a racing car was a day lost, and he savoured every opportunity to pound around the nearby autodromo, then passing the evening playing cards and drinking wine and talking racing.

It was an existence he found completely fulfilling, and the association with Maserati, whom he joined in 1955, was the happiest of his racing life. Gordini had been fun, but after four seasons the chronic lack of both pace and reliability had become wearisome to one now recognised as among the world’s top drivers.

Raymond Mays (for whose BRM team Behra later drove) once related to me an anecdote very revealing of Jean’s love affair with his job. “I don’t think he could ever quite believe his luck that people would actually pay him to drive racing cars.

“He was a magnificent little driver, and a charming man, but terribly temperamental in a French sort of way. If things weren’t going too well, he sometimes got a bit demoralised, but he was never depressed for long, and I asked him how he kept his spirits up.