Tomorrow's World

With about 100,000 online viewers for the 2018 Gran Turismo Championships World Finals in Monaco last November, you’d think the 100 or so gamers were all salaried competitors. After all,…

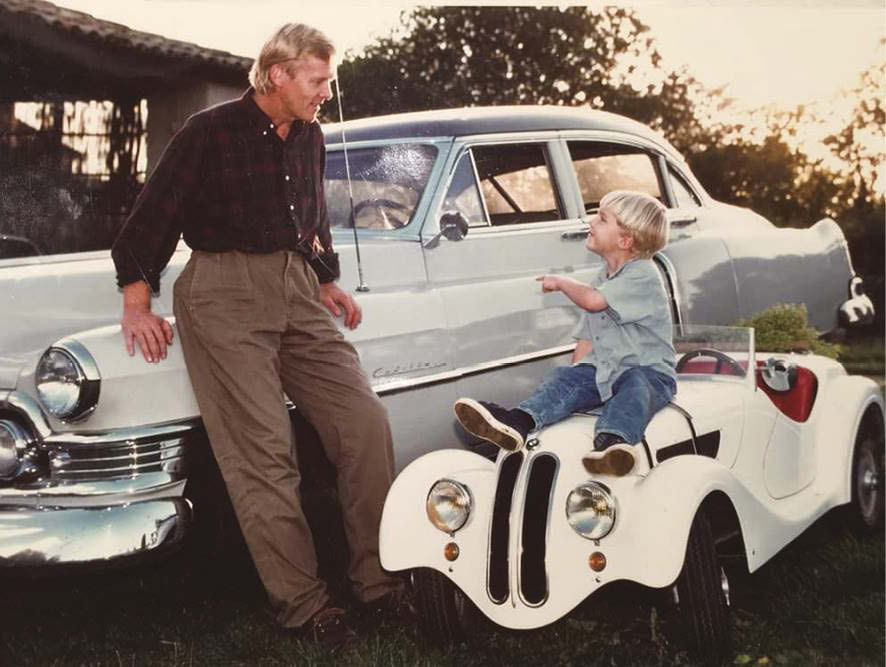

The Vatanen name has made a sizeable impact in the world of rallying, and latterly also the world of politics. While most know Ari Vatanen as the 1981 World Rally champion and four-time Dakar Rally winner, he was also a Member of the European Parliament for a decade until 2009. His son, Max, is focused on forging his own rallying career, with a handful of WRC outings across both the junior R2 and R5 categories already. He’s without a seat this year, but soon to return. Plus, politics hasn’t interested him just yet…

Ari: It’s not false modesty on my part when I say I would have liked to have been a better father than I think I have been. When Max speaks so warmly of me, I feel that I barely deserve it.

You can have all the glory, fame and money in the world, have achieved incredible things in sport, or within the European Parliament, but life is about your family. That’s what matters. If you fail there, and empty walls are waiting for you when you come home, there is no substitute for that.

There can be no doubt that there were times that the relationship between Max and I became strained. I didn’t want to go to too many of his rallies, because I didn’t want to put that pressure on him. But when I eventually did, there were problems.

One time, I was waiting at the end of the first stage, and counting the cars through by their number, and he wasn’t there. He’d crashed, but there was more to it. He was driving with a new co-driver – who wasn’t a top-level co-driver – and he had only called the notes for a fast right-hand corner, and unfortunately immediately afterwards there was a tight left-hand corner, so Max arrived far too fast and never made the corner.

I couldn’t understand it. So I kept on at him, ‘Why did you crash on the first stage? You should have been going more carefully! Why didn’t you make the corner? What were you playing at?’. On and on I went. Poor Max was shattered by the experience.

Later we watched the onboard footage of the accident, and I could appreciate what had happened – that it wasn’t Max’s fault. I tried to beg his pardon but it was too late, because I’d knocked his confidence, and to this day, I feel very bad about my reaction and I have asked him to forgive me, as I know the impact it had on him.

That’s the problem for parents. You can never say you did everything as you should have done. There’s a special relationship between a father and his son, so when your father tells you off, it hurts you a lot more than when your team manager tells you off.

I was amazed at his speed and talent, though. I used to ask myself, ‘Where has this come from?’ Because I never coached Max, and he was so late in expressing an interest in becoming a rally driver. No question about it: he had natural talent.

What I also appreciated during Max’s time in rallying is that it is the most awful feeling, waiting for your loved one to finish, safe and sound.

My poor wife, Rita, has had to endure so much. Most people know all about my near-death experience, after cartwheeling at around 120mph, during the 1985 Agentina Rally. Rita only found out by watching the news on the television, as the team didn’t have the phone number for where she was staying at the time. I can’t comprehend what she went through.

“I was close to being paralysed by a crash in Corsica”

Even after my experiences, some mothers might have said to their son, ‘No, my dear son, you shouldn’t go rallying’ but Rita is too wise for that. She knows that life is greater than we are.

What few know is that in 2011, driving the course car at the Corsica Rally, I had another bad crash that came close to leaving me paralysed.

I was driving a Peugeot 207 RC, with Max alongside me, and there was a fault with the brakes that meant the pedal went solid, as the piston in the brake cylinder had jammed, and so there was no braking power. We left the road and dropped with a nose-first, hard landing. I immediately felt pain in my neck; at the hospital in Bastia, doctors discovered a vertebra had slipped and nearly hit my spinal chords. I had to be stabilised then flown to Marseille hospital for an operation to put things right. The surgeon said I was lucky not to be paralysed from the neck down. I have four screws and a plate in my spine.

After that, Rita and I decided that there would be no more competitive events for me!

However, I still hold a pilot’s licence. To this day, it’s as exciting for me as it is for someone climbing into a helicopter for the first time, and I probably average 50 hours a year. Flying around Provence, over the mountains, is magical, and whenever I go to the 1000 Lakes Rally I’ll hire a helicopter in Sweden and enjoy two or three weeks of buzzing over the fjords around Finland.

The human side to rallying used to be so much fun. During the recce times, it was more relaxed and very social, with all the families travelling with drivers, lots of practical jokes being played on one another and a feeling that life was good. All of that has gone away now.

With Max’s driving career on hold, we need a plan. Who knows, perhaps the Vatanen name could be used to create a world-class driving school, and give something back to the sport and aspiring rally drivers? It’s too early to say for sure, but what I do know is we’ll never be far from the sport we love.

Max: We were in the sauna when I told Dad that I wanted to get into rally driving. It was a total surprise for him. He’d never pushed me in that direction, and I’d never shown an interest in my young age.

So when I asked him whether he thought I was too old to start rallying, he was quite emotional; I don’t think he’d expected me to ever ask.

I genuinely didn’t know what he’d say, but of course he said: “Max, it’s never too late in life to do what you want to do.”

Mum, on the other hand, was anxious. Not against it, because like Dad she encouraged all her children to live their lives to the full, but she’d been through so much with Dad and knew the risks very well.

In a way, I’d been a little cunning. I had been studying at a business school, in France, and we had to do an exchange as part of the course. So I spoke with my professor, ruled out Miami and Sydney, and told him I wanted to go to this tiny place called Mikkeli, in Finland.

Why? Because it was three hours from my Dad’s home village, Tuupovaara, where my Uncle still lived. We had a Ford Escort MkII stored there, so on a Friday afternoon I’d drive three hours to Tuupovaara, so I could spend all my weekend learning how to drive properly – without my parents knowing what I was up to.

My first rally car was a Renault Clio, in the [SC6] V1600 class, which is basically a Clio with a roll cage and race seats, and few modifications allowed. By the time that I made it to my first rally, I’d finished my exchange for my bachelor of business administration the day before, so my head was clear for rallying!

Dad came to that first rally. In general terms, you’d imagine that having a world rally champion on your team, so to speak, would be an advantage. But if anything, it’s more of a disadvantage. In my experience, it made it more difficult to find sponsors, because there was always the underlying feeling that people would say to themselves, ‘He doesn’t need any sponsorship money. He’s the son of a world rally champion.’

There were other issues, too. If I crashed, he’d be disappointed because he knows you can do better. But it’s not like a team manager being disappointed, it’s your father, which is a more complicated relationship, and the tension it created meant it took me many more rallies before I found my pace again, because I was so worried about upsetting him. Ironically, it was coming from a good heart, but we soon agreed that he would take a back seat, so there was no danger of him crossing the line between a professional and emotional response. And I should add, I couldn’t have got to where I am without his support.

The sad thing for today’s rally drivers is that there are so few competitors who can make a living out of it. Take tennis; the top 100 players can make a living out of it. If you counted the number of drivers that can make their living out of rally driving, it’s not a lot compared to the scale of the sport.

It’s become so much more expensive since Dad’s day, too. Which means that teams are much more risk-averse now. Dad would never have got away with all the accidents he had back then, now.

I have no drive for this year, and am working away on new projects, including driver coaching, and perhaps Dad and I will be able to share some news about this soon. Coaching is satisfying, but a lot of drivers need, well, a lot of help when it comes to driving on snow and ice. And where better to take them to learn than Finland?

Am I proud of Dad? Of course I am. He started his life in a small village in Finland, without a father, went after his dreams and achieved so much.

Yet it’s not so much these achievements, in motor sport or as a politician, that make me proud. It’s who he is as a person, and the kind of father he has been for me. Whether you are successful, have a lot of contacts, or are rich, you’re no better than somebody who lives a simple life, out of the spotlight. It’s about your qualities as a human being. James Mills

Follow James on Twitter @squarejames