Centenary meet

ln October 1897 the Hon Evelyn Ellis ascended Worcester Beacon in the Malverns on his Daimler, specially equipped with three sets of brakes and low gear ratios. To commemorate this,…

Forget, for a moment, Charles Leclerc’s unfortunate qualifying accident in Baku just as it looked like he was about to dominate the whole weekend and thereby go some way to compensating for the late loss of victory in Bahrain two races earlier. His mishap put in place a set of circumstances that allowed Mercedes to sweep to a fourth 1-2 (Valtteri Bottas ahead of Lewis Hamilton), thereby disguising the competitive state of play between the two teams at that point. Four races in, on pure underlying performance it should have been Mercedes two/Ferrari two.

Instead, Baku just underlined the all-round excellence of Mercedes. With Leclerc sidelined, they locked out the front row through cunning – effectively denying Vettel pole by a bit of choreographed trickery as they all left the pits for the final Q3 runs.

Pulling to the side – ostensibly to practise starts – just as Vettel had followed them out, trying to get their tow, left the German having to do his lap without the powerful slipstream reward down the long straight running alongside the Caspian.

The Mercs then each picked up tows worth 0.3sec. Vettel’s untowed time fell 0.2sec short of pole… Before crashing, Leclerc appeared to have had about 0.3sec on Vettel at a track where he always flies. But he seemed just a little too determined to make his mark, to get out of the support role, to shade Vettel – with disastrous consequences. Without that, it looked likely to have been a Ferrari front row lock-out. Instead, it was all silver, Bottas and Hamilton taking care not to touch through the first two turns in a way they wouldn’t have done if they’d been in rival teams. Bottas prevailed – and thereby took the win he was denied by a late puncture last year.

Two Ferrari wins from four would, of course, have given a very different perception to the prospects for the season ahead. But even had Leclerc not suffered his electrical glitch in Bahrain, even if Sebastian Vettel had not spun there when dicing with Hamilton and even had Leclerc not crashed in Baku qualifying, there were still some worrying underlying patterns. Worrying for Ferrari, that is.

The implications of the 2019 regulations have moved Mercedes and Ferrari further away from each other in how their cars work (see column, page 23). Their performance patterns have thereby become much more distinctive and circuit-specific. Ferrari was fast in Bahrain and Baku, but not elsewhere.

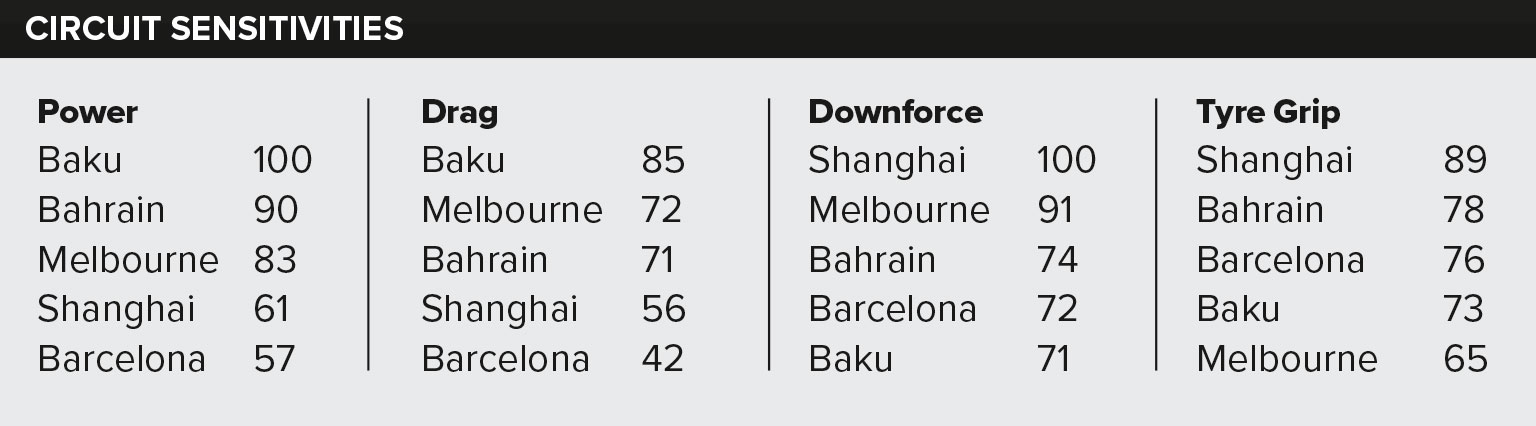

So what was it about Bahrain and Baku? F1 teams work a lot with ‘circuit sensitivities’ and there are some vital clues to be found there. They measure how sensitive each circuit is to power, downforce, drag and tyre grip. There is an enormous variation. Therefore there’s a big performance swing between two cars that are strong or weak in different areas.

Using index figures, the table below shows how the tracks up to Spain compared in those sensitivities. The index figures of 100 for Baku in power sensitivity and Shanghai for downforce reflect the fact that they are the most sensitive of all the tracks on the calendar in those measures. It means that extra power will find you more lap time at Baku than anywhere else – and that the same increase in power would find you only 57 per cent as much lap time in Barcelona as it would in Baku. Conversely, for a given increase in downforce you’d get maximum lap time benefit in Shanghai and only 71 per cent as much in Baku.

Which is a roundabout way of explaining that the potential pre-Barcelona score of two apiece (if results had followed the actual performance of the two cars) was heavily skewed in Ferrari’s favour by the fact that we had just visited two tracks that give a big lap time reward for extra horsepower, one of which (Baku) also heavily favours low drag. The Ferrari has a power advantage over Mercedes and lower drag. The Mercedes has a significant downforce advantage over Ferrari, hence its superiority at Shanghai was no surprise – and it goes some way to explaining its great pace in Melbourne.

But it’s significant that Baku and Bahrain are outliers in the general global demands of all tracks. Which others might suit Ferrari? Montréal, Spa, Monza – that’s it.

So with battle renewed around Barcelona, a circuit with a much more ‘normal’ set of demands, we were set to see a more accurate picture of how the competitive order really stacked up – and therefore a more likely indicator of future performance. Add into that mix a massively powerful upgrade from Mercedes around its barge boards and front wing – reckoned to be worth more than 0.3sec. Ferrari had fewer updates and a small further increase in engine power.

Bottas took his third straight pole – 0.8sec faster than Vettel’s third-placed Ferrari. Through the slow turns of the short final sector, the Mercedes was more than 0.6sec quicker than the Ferrari. The latter was taking about 0.1sec out of the Merc in the straight-dominated first sector, where its drag and power were rewarded (but not by anything like as much as in Baku or Bahrain). The Merc’s downforce advantage over the Ferrari is at its most extreme in slower corners, but it was more than that: there is something in the W10’s rear suspension (and perhaps also in the software for the brake-by-wire) that allows it to maximise the tolerances allowed in regulations that ostensibly ban four-wheel steer. The wheels are not actively steered, but there is a simulation of that – and a breakthrough in how to set this up came from Hamilton’s feedback in Baku. It worked devastatingly well through Barcelona’s slow turns.

All of which was pretty devastating for Ferrari after the outward hope (albeit frustrated) given by Bahrain and Baku. “Our car’s limitations have become clearer this weekend,” said team chief Mattia Binotto. “There is an understeer balance and not enough downforce. They have been there at the other races. But how long it takes to address is difficult to answer. It may even be the car concept.” It’s rather beginning to look as if the momentum built up by the great Ferrari chassis of 2017 and ’18 – which were arguably faster than Mercedes more often than not, as an average – has been brought up short by the change in regulations for this year. That and continued Mercedes excellence in every department.

So all that was really left to be decided was which Mercedes driver would win. Bottas had arrived here one point ahead of Hamilton and very much maintaining the momentum his season-opening victory had given him. After also winning Baku, his pole in Barcelona really laid down the gauntlet.

It all came down to a clutch vibration for Bottas at the start – which allowed Hamilton alongside on the run to Turn One. Bottas was planning to try for Hamilton’s outside through there, but had to abort that plan when Vettel’s Ferrari appeared on his left, squeezing him somewhat. Vettel flat-spotted a front tyre in that moment, allowing Mercedes its Hamilton-Bottas 1-2, and also paving the way for Max Verstappen’s Red Bull to take third. Vettel’s lock-up also left Ferrari with yet another awkward set of decisions to make regarding moving Vettel aside so that Leclerc could chase Verstappen. It took a while to do so – and later lost Vettel time by delaying moving Leclerc aside when they were on different strategies. The tentative calls were really not the Scuderia’s biggest problem, though. Nor F1’s…