Nissan's R89C — the beast from the East

It looked the part but Nissan’s thirsty, big-budget R89C, which was campaigned in the World Sportscar Championship and Le Mans in 1989 and ’90, was dogged by technical problems. Doug Nye dissects Japan’s powerful Group C contender to find out why it was no match for the Sauber-Mercedes and Porsches

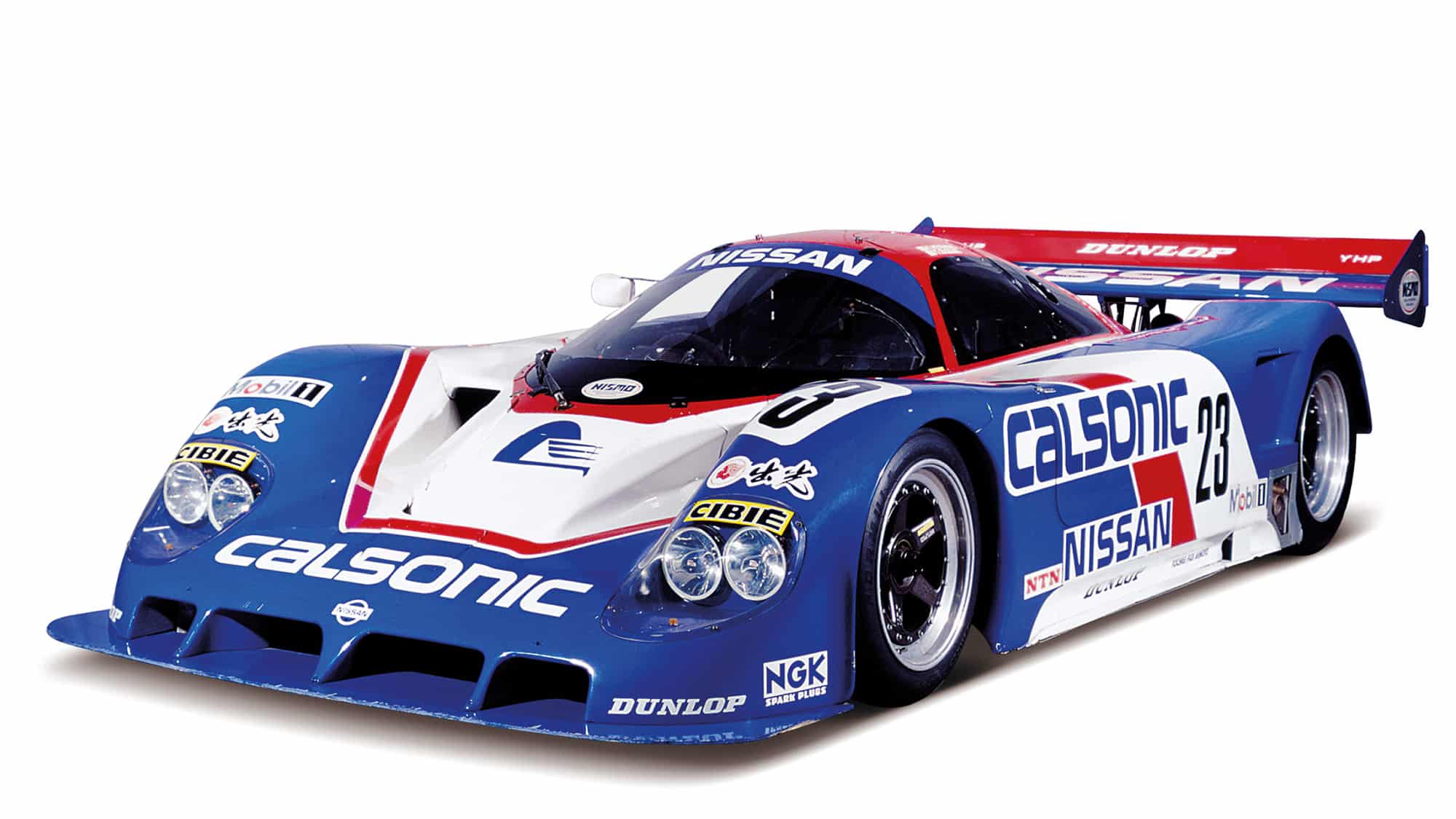

Nissan R89C No23 at the Nürburgring in 1989; Nissan often race with this number – ni in Japanese is two, san is three

Nissan archive

At the end of a year in which Honda of Japan have shone so brightly in Formula 1, let’s spool back some 30 years to the Group C World Sportscar Championship contender fielded then by rival major Japanese manufacturer, Nissan.

The name Nissan is derived from Nihon Sangyo, meaning somewhat disappointingly just ‘Japan industry’. Before World War 2 the Nissan Group absorbed DAT, making motor cars under the Datsun brand. The wider Group’s wartime activities in support of the Japanese military left it with a tainted image, and so its cars were marketed under the Datsun brand name until a rather more forward-thinking management decreed resurrection of the Nissan title across global export markets from 1981.

That growth in Japanese industrial confidence and ambition into the 1980s helped the nation’s three major motor manufacturers, Mazda, Toyota and Nissan, follow Honda’s lead in recognising the promotional possibilities attached to top-level racing. The industry had become world leaders in producing reliable, dependable passenger cars for mass sale – but most were, in essence, pretty grey porridge.

Around the same time that competitive stirrings were afflicting the loins of high-ranking Japanese motor industry executives, the FIA had introduced its fuel consumption-conscious Group C endurance racing category, contesting the revived World Sportscar Championship (widely known as the WSC).

Nissan supplied engines to private teams contesting Japanese national championship races in 1982-84. In 1983 Hoshino Racing bought a March 83G chassis to carry Nissan’s developing four-cylinder turbocharged engine. Meanwhile, in the USA, long-time Datsun SCCA racing exponent Don Devendorf ’s Electramotive had in-house engineer John Knepp develop a 3-litre Nissan V6 ZX production engine for both IMSA and Group C racing. The IMSA unit retained an iron stock block while for Group Ca 60-degree V6 aluminium block was created. With twin turbochargers it was capable of producing around 1000bhp.

Nissan in Japan had founded Nismo (Nissan Motorsports) directed by Yasuharu Namba to race works cars between 1984 and a maiden entry in the WSC at Fuji in 1985. Three new March 85G chassis were acquired, two carrying the new alloy engine, and it was this pair of 3-litre March-Nissans which appeared in that race. Drivers Kazuyoshi Hoshino and Masahiro Hasemi set the fastest two times in first practice before the two works Rothmans Porsches took a grip. Apparently divine intervention then caused the Fuji circuit to be rocked by earthquakes and a monsoon rainstorm. The European teams deemed conditions too unsafe on their Goodyear and Dunlop tyres and withdrew pre-race, leaving the Bridgestone-shod March-Nissans to win for Nismo, Hoshino lapping the entire field.

“The turbo kicked in and I nearly wiped out a bystander – the Lola boss”

Four new March 86Gs were bought for 1986, Nismo running three of them with the V6 turbo engine. One works car and an older 85G were entered for Le Mans that year and experienced British team manager Keith Greene was hired to direct operations. Sadly this pilot Nissan Le Mans operation proved farcical, with a cultural clash between the Japanese driver/management faction and its British counterparts. The 86G broke its crankshaft after six hours, and the 85G limped home only 16th.

Nissan then built a new 3-litre 90-degree V8 engine for 1987, tailored to Group C in new March 87G chassis. Other than an entertaining proclivity towards igniting their cars during refuelling –a Jaguar mechanic remarking “Aah, they must be full now” as a Nissan mechanic flailed past with his overalls alight – the Japanese marque flopped again at Le Mans.

For 1988 the VEJ30 engine was abandoned, and specialist Yoshimasa Hayashi designed a fresh 3-litre, using the same 90-degree V8 layout and 66mm stroke to retain the same crankshaft. At Le Mans both cars’ engines failed almost simultaneously.

The all-black test car

In the pits at the Le Mans 24 Hours in 1989

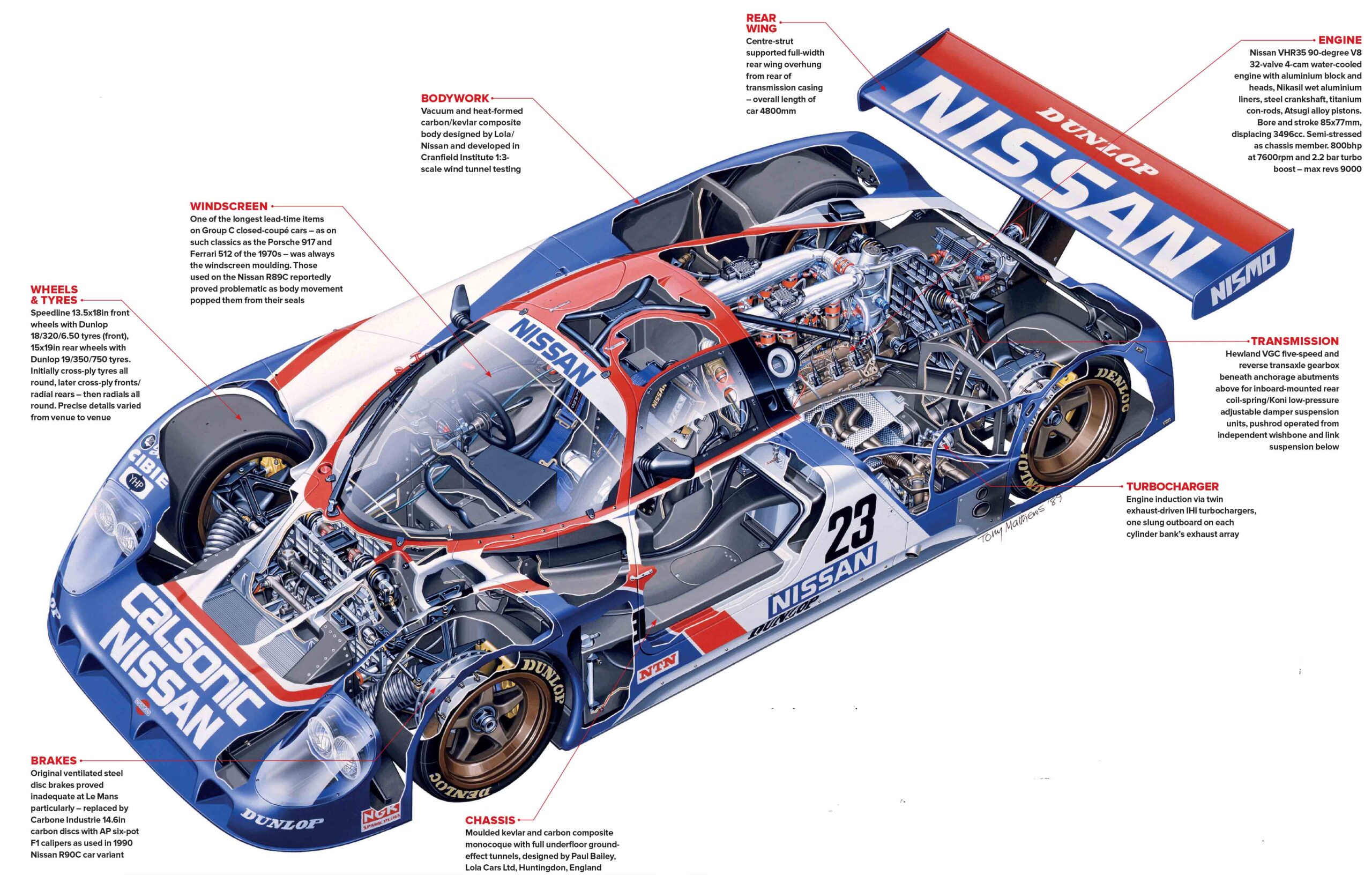

Nissan’s management still coveted Le Mans success. Group C regulations for 1989-90 initially decreed that any manufacturer wishing to compete at Le Mans also had to contest the WSC. Nissan approached Lola for all-new composite-chassised cars, the first becoming the Nissan R89C. Two completely separate racing operations were launched – both to use a new 3.5-litre VHR35 V8 engine with 77mm stroke crank. Nissan Motorsports Europe (NME) was based in Milton Keynes, run by Howard Marsden and Keith Greene, to concentrate upon the European FIA events. Nismo Japan contested the Japanese Championship and ran alongside NME in the Japanese WSC round re-homed at Suzuka.

At last Nissan had a sensible race programme, well engineered and well run, and although the R89/90Cs struggled with reliability through their first season, in 1990 Nissan would finish third in the FIA Teams’ Championship – but without a race win.

Cabin-liveried R89C in the 1990 Suzuka WSC round

For 1991 Nissan closed the NME arm and concentrated its support on Devendorf ’s Nissan Performance Technology Inc (NPTI) team in America – running both in-house-built NPT90/91 chassis and the R90C composite cars in the US IMSA Championship series. Nissan sorely wanted to return to Le Mans, but in response to rival-team protests against it doing so on a one-off guest-entry basis – ignoring other WSC rounds – the FIA refused. So the 1991 Le Mans 24 Hours was run without Nissan entries – and Mazdaspeed scored the Japanese industry’s first win there. The fact that the ear-splitting little Wankel-engined Mazda pulled off that coup on a budget of barely £400,000 against the millions invested by Nissan simply added to the humiliation.

Julian Bailey was one of Nissan’s 1989-90 team drivers, but recalls how “It could have begun really badly, because the first time I drove it in bare unbodied form in the car park at Lola’s, the turbo kicked in, took me by surprise, and I nearly wiped out a bystander – Eric Broadley, the Lola boss.

“They were a nice team to drive for, a great atmosphere, though we had a few issues with the car – especially that first year, ’89. The engine was fantastic, vast power, too much in fact for our cross-ply Dunlop tyres. One big change was to fit radials at the rear, cross-plies on the front, and that at last allowed us to cut wheelspin and put the power down. Compared to those Group C cars, F1 was easy.”

Through 1989 the new Lola-chassised R89Cs – four of which were built – proved very fast in a straight line but difficult to set up, and dogged by initially poor brakes until a change was made to carbon discs. The cars also had a habit of popping out their windscreens.

Nissan team manager Keith Greene – who died earlier this year – in conversation with Julian Bailey at Dijon-Prenois in 1989

The 1989 opening championship round at Suzuka featured Toshio Suzuki/Kazuyoshi Hoshino finishing fourth in Nismo’s March- Nissan R88C. Round 2 at Dijon-Prenois then had Julian Bailey/Mark Blundell finding their feet in endurance racing with their R89C, qualifying sixth – and at Le Mans, as Julian Bailey recalls: “The car’s aero worked really well; we had telemetry and I was the only one to take the Mulsanne kink absolutely flat, at 248mph… Scary! But the car gave some confidence apart from the brakes, a soft pedal at the end of the straight, and I punted Nielsen’s Jaguar up the back when the pedal just hit the stops, and then I locked up the rears. We had to pump the brakes with the left foot, and on that lap I just hadn’t. The team weren’t very happy.”

A first finish came at Jarama, Spain, Bailey/ Blundell eighth, and at the Nürburgring teammate Andrew Gilbert-Scott wrested the race lead from the normally dominant Saubers and ended his stint 30 seconds in the lead. Unfortunately the Nissan was running well over its fuel allowance and was forced to slow and fall back, finally running dry with three laps remaining. Then came the Donington Park round. Julian Bailey: “The Saubers had a bigger low-revving engine, more torque, and they just pulled away – but Mark Blundell and I led for a while before a tyre problem and we finished third there and I set fastest lap.”

Mark Blundell and Julian Bailey (in the car) were co-drivers in five of eight rounds in 1989’s WSC, with two podium finishes

At fast and fuel-thirsty Spa, NME opted for an economy chip in the R89C’s engine but Bailey/Blundell again placed third while they finished 12th in the final round in Mexico City.

Into 1990, Keith Greene was ousted from NME, being replaced by Dave Price and Bob Bell from Sauber. The team ran two cars with much the same V8 engine in an updated R90C version of the Lola chassis. Kenny Acheson and Gianfranco Brancatelli took the second car with Martin Donnelly and Raul Boesel as occasional team-mates, while Bailey/Blundell retained the lead car.

Nismo Japan entered an R89C in the year’s opening round at Suzuka, Anders Olofsson/ Masahiro Hasemi finishing third while thereafter NME flew Nissan’s banner. Fortunes had improved but like Jaguar they could only pick up crumbs from the Mercedes-Benz banquet. Wheel nuts fell off at Monza and Silverstone, but the now reliable V8 engine retained its fuel-thirstiness – having to finish most races with the boost wound right back.

For Le Mans 1990, Nissan’s effort was huge – running five cars, two R90Cs from NME, two prepared by US-based NPTI and one from Japan. Two semi-works R89Cs also appeared, one from Team Le Mans, the other from Yves Courage. Nissan logos appeared everywhere at La Sarthe, 21 drivers employed. Blundell qualified on pole using a ‘super-bomb’ engine which he thought “had its turbo waste-gate jam open”. Bailey/Blundell/Brancatelli led on Saturday evening until the latter smashed into Suzuki’s Toyota entering the Dunlop Curve. Brabham/Robinson/Daly in the lead NPTI car challenged for the lead before a fuel leak ruined their race.

In other championship rounds, Bailey/ Acheson finished seventh at Monza, third at Spa; Bailey/Blundell third at Dijon. At the Nürburgring Blundell drove solo to finish fifth, Brancatelli/Acheson ninth. Brancatelli/ Acheson and Bailey/Blundell finished 4-6 at Donington, but at Montreal, Bailey led while Acheson hit a manhole cover which had became airborne, three following cars hitting it and leading to the race being red flagged. The Bailey/Blundell Nissan was placed second.

“I was the only one to take the Mulsanne kink absolutely flat, at 248mph”

Mexico City brought the end of fuel-regulating Group C competition, and ironically Nissan Motorsport Europe’s most successful and last WSC race. When Schlesser/Baldi’s Mercedes was disqualified for having taken on 0.1 litre too much fuel, the sister car of Jochen Mass/Michael Schumacher was declared winner. The Germans had caught the Bailey/Blundell Nissan when it had been leading, before in the words of one report it “had proved absolutely lethal on its Dunlop wets” once the heavens opened in the last 15 laps, losing up to 15 seconds per lap. The sister R90C of Acheson/Brancatelli finished fourth.

Nissan’s board had decided to abandon European and WSC aspirations and concentrate upon Devendorf ’s successful NPTI operation in IMSA. With Geoff Brabham, NPTI would win four consecutive IMSA GTP titles for the Japanese marque, 1988-91. Geoff recalls: “In 1989 our Nissan IMSA team went to Le Mans basically as a reconnaissance mission to learn. I drove for the European Nissan Team with my US team-mates. We were not their number one priority, but we did OK until the engine failed. The main thing in my mind was the brakes being terrible. At the end of the straight I was hard on them hoping to stop and the Mercedes, which won, came straight past on full noise before braking. I was not happy!

“In 1990 the US team prepared and ran the car. Nissan had three teams, European, Japanese and US, all run separately. We were unlucky as halfway through the race we were swapping the lead back and forth with the Jaguar – the US-run Jag funnily. It was like an IMSA race. Anyway, at that point we were OK on fuel and the Jag wasn’t, so we knew they had to slow down. But the fuel-tank bladder split and put us out. It was really disappointing as we could have been the first Japanese car to win, which would have been really big.

French team Courage ran an R89C at Le Mans 1990 with Hervé Regout, Costas Los and Alain Cudini driving, finishing down the field in 22nd

“The Lola was not a good car. It did OK in the long-distance races but when I first started driving for Nissan it was a struggle as the chassis and aero were not good in the higher-downforce shorter races. It wasn’t until Nissan USA built its own chassis and aerodynamics that we started to win. Kas Kastner was the general manager and the link between the team and Nissan USA. Trevor Harris designed the chassis and was my race engineer, and John Caldwell built the engines. The US team operated on its own funded by Nissan USA.

“Actually the US GTP car had way more downforce than the Lola, but nowhere near the downforce of the Dan Gurney Toyotas in 1992/93 or the Peugeot I won Le Mans with in ’93. The dominant Nissan IMSA cars had great engines, good chassis and an awesome team. But aero-wise they were not as good as the designers tried to make out. The Toyota seriously kicked our butt in the end.”