Etancelin's Maserati on Show.

Philippe Etancelin's first big victory of the season, when he vanquished the Ferrari Alfa-Romeos at Dieppe, has been the cause of his Maserati being displayed in the showrooms of the…

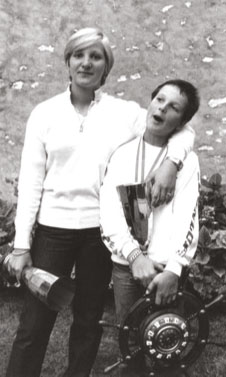

The Muller siblings have been there and seen it all in motor sport. Yvan’s storied career will more than likely ensure that he’ll go down in history as a tin-top legend, having racked up four World Touring Car Championship titles alongside a British success, and topped the Andros Trophy ice racing series. He’s even dabbled in rallying. Cathy has been alongside him most of the way, and her own racing career spans International F3000, Indy Lights and a Le Mans 24 Hours start.

Interviews by James Mills

Yvan: “I despair of some of today’s new generation of race drivers. They talk about giving racing their ‘maximum’ but they don’t know what that means. They spend more time on social media than they do looking at their data. Sometimes, when running my own team, I was putting in more motivation and energy than them, which was frustrating.

To be successful, and win races and championships, I gave up friendships, parties, generally enjoying life. I didn’t do any of that. From the age of 20 to 40 I was looking only ahead and never to the side; it was all about racing. But that’s what it took for me to arrive at this level.

Unless you are super-talented and can arrive quickly at the top level, you have to make sacrifices. You can’t make excuses, and have to learn from your mistakes.

Fortunately, Yann [Ehrlacher], Cathy’s son, understands that. He is talented and hard-working. Some other young drivers are not ready to put themselves in that position.

I like to think that Yann benefits from the experience of both his mother and I. And Cathy is slightly less stressed by knowing that I am there to help guide him. It’s only right that I do, because early in my career she helped me.

People often say she was my manager, but that’s not true. A manager takes your money but doesn’t do a lot! She didn’t take my money and she did such a lot for me, because she is my sister. She was more like a mentor, because she had previous experience and could tell me what to expect and how to handle situations.

She was almost ahead of her time. Back then, sponsors weren’t interested in women in motor sport. I think that today, in times of equality, sponsors would take more interest in a driver of Cathy’s ability.

Cathy was always a very fast driver – as fast as anybody, when the set-up and conditions were there. Look at karting: she won the European Championship [the Individual European 100cc Championship] in 1979, and was the only girl there. She was almost ahead of her time. Back then, sponsors weren’t interested in women in motor sport. I think that today, in times of equality, sponsors would take more interest in a driver of Cathy’s ability.

I never thought I could be a professional driver. Karting was just a hobby, a pleasure, but step by step, as we moved up the series, won some races and championships, we took it more seriously.

After moving into Formula cars, I won the British Formula 2 Championship and had my sights set on F1. But I needed European experience as well, before F1, so I moved up to F3000 and had a lot of problems with limited budget. The F1 teams wouldn’t listen to me.

I thought that would be the end for me – no more racing, time to get proper work – we did a lot of things but life has to move on. But then I had a phone call from Hugues de Chaunac at ORECA, which had two BMWs in the French Touring Car Championship, and he was looking for an extra driver. There were 10 or 12 guys on the list and, sure enough, he took me.

I never looked back. Of all the national championships, I really enjoyed the BTCC. It was the most exciting because of the circuits, the cars, drivers and the contact, which is why I asked Audi Sport whether I could switch from Germany to the UK.

Guys like Thompson, Plato, Tarquini, Menu, Priaulx… all those guys were at a high level and to beat them and become a champion meant I had to push myself, and it’s probably why at the age of 50 I am still a paid and competitive racing driver, because of the experience of racing those guys. I can’t have any regrets.

However, my life was racing. I was spending at least six months on the road, at races and tests. Even when I was at home, I was thinking about racing all the time; I don’t need to be away to be consumed by it.

When I decided to give up in 2016 I was very pleased to stop. It was my decision. When a new offer to drive was made, it had to be on my terms, with my team, so I secured the money for my team on the condition that I would be one of the drivers.

The way I see it, the year I stopped was a good move because it all worked out for the best. Now, if I intend to retire, there will be no official announcements. I’ll go quietly – but only once I’m not enjoying myself any more.”

Cathy: “Sometimes I wonder whether I was ahead of my time and I think I would like to be a woman racing today, because the environment is quite different. But I have no regrets because I am who I am today because of the hard time I had when so many in motor racing did not want a girl or woman to be driving.

Dad would go hillclimb racing at weekends, in a Group 2 BMW 2002. I was around the scene, I liked it, and then one year we were on holiday, visiting our grandparents near Valencia, and I had my first drive of a kart. I loved it.

So my father bought me one, and the guy who sold it to us said I should get a competition licence and race after watching me drive. So that’s what we did. It wasn’t easy; both our parents worked and were busy people but they impressed on us the values of dedication and hard work. I can remember that we had to strip down, clean and rebuild our karts in a small, bare garage, with no heating, and sometimes it would be -10degC and we would have to use petrol to clean it as water would freeze.

Once competing in karts, I was good. So good, in fact, that for the regional races Dad asked whether I could race against the adults, as I wasn’t learning much from children of my age.

The organisers agreed, but said I would have to start last. Toward the end of the first race I had overtaken everyone bar the leader and was closing, but they waved the chequered flag two or three laps early.

In karts and cars, boys and men would rather crash into me and take both of us out of the race than be passed by a girl. Yet when Yvan and I ran an F3 team together in the French championship, the cars were the same colour and so were our helmets, so they wouldn’t try and crash into us because they weren’t sure if it was Yvan or me!

Jean Alesi joked with the other drivers that he had seen me peeing against a tree, standing up; I had to be a man, he said.

I came up against that sort of attitude a lot. Another time, when I was 18 years old, I entered the Volant Elf-Winfield competition [in 1981]. There were 300 drivers, and I made it to the last six, then I proved to be the fastest of all. The judges’ attitude was ‘No, not possible’ and they decided that I and the second-fastest driver had to go again. I went faster still. So they insisted we change cars. Still I went faster.

My best ever memory, however, is of the European Formula 3 Championship when I won the race at Albi. My mechanic with the Mario Crugnola team wrote ‘Grazie’ on the pitboard. It pleased me greatly. I was the only driver not to lift off in the triple right-hand corner [Armand Brouzes]. Jean Alesi joked with the other drivers that he had seen me peeing against a tree, standing up; I had to be a man, he said.

They put the car in parc fermé and examined everything in detail, but that’s just how it was. It made me more determined.

Probably my other highlight was driving a Porsche 962 to seventh place in the 1000km race at the Nürburgring. I wasn’t able to test the car before the race but was as fast as my team mates and loved the power and exact feeling of the car. I would have liked to do more sports car racing, but the trouble was sponsorship. Nobody wanted to sponsor a woman, and I never knew whether I would be able to race from one season to the next.

When Yvan was very young, I would sit him on my lap and take him out in my kart. He’d steer while I did the pedals, and once he was old enough he got a kart and I taught him how to maintain it and showed him racecraft by driving in formation.

I am incredibly proud of him. He is so professional and committed and it shows, to be nearly 50 years old and still at the top. Yet he will sweep the garage, clean the glass on the cars, spend hours with the engineers on data and set-up. The young drivers look at him as though he’s strange, but that’s what it takes to be a champion.

Now it feels as though the family adventure has gone full circle – almost. Yvan has been there for my son, Yann, and they are now team-mates. He has taught him the same values our parents taught us.

What would be nice is to see Yvan’s [six-year-old] daughter complete the circle and join the adventure.

Follow James on Twitter @squarejames