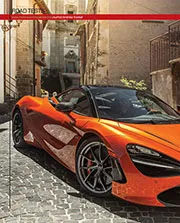

McLaren 720S

Its performance is otherworldly, which means you’ll struggle to make full use of it in the real world | BY ANDREW FRANKEL When you slam shut that extraordinary door for…

A few days ago I had a fascinating but sadly unattributable conversation about electric cars with an engineer from a company that has some sporting cars in its portfolio. And I was explaining that while I could see very easily how electric cars could make quite good replacements for petrol or diesel when used as mere transport, I could not see how to make a proper electric sports car, not least because the sound of a car (or lack thereof) is so important to the driving experience.

His take was interesting: those of us who have been around for a bit were brought up on the sound of the internal combustion engine; it has worked its way into our brains to such an extent that it is so expected when we get in a car, we feel uncomfortable when it is absent. This will not be the experience of the younger generation brought up on the near-silent whirrings of electric and watching Formula E and its offspring on telly. They won’t miss the howl of a V12 or the thunder of a V8 because they won’t have heard them in the first place, certainly not long enough for their sound to become hard-wired.

It’s an interesting point, but flawed, I feel. You may not miss what you have not heard, but that does not therefore make what you are hearing inherently easy on the ear. We’ve all grown up to the sound of washing machines, refrigerators and other electrical white goods and I’m yet to hear anyone wax lyrical about how their Zanussi sounds.

What’s the answer? It seems to me the problem is not the internal combustion engine, but the fossil fuels we use. So why can we not use a renewable source of fuel instead? In short, why not use the same hydrogen than many reckon will in time replace batteries and instead of using it in a fuel cell, burn it in an internal combustion engine? You have a clean fuel the world needs with the sound and response characteristics we enthusiasts want.

If this sounds pie-in-the-sky, it’s actually pretty old tech. About 15 years ago I drove a BMW 7-series powered by a 6-litre V12 that could swap between on-board supplies of petrol and hydrogen at the literal flick of a switch. It was called the Hydrogen 7.

As I understand it, the project failed for a number of reasons, primarily the poor energy density of hydrogen versus petrol (meaning it needed four times as much of the stuff to travel the same distance) and the fact that at the time the only financially viable way to get the hydrogen was to extract it from natural gas, thereby burning a fossil fuel. But the world in general and the renewables landscape has changed beyond recognition since then. I’m not saying it would be viable now and there may be many engineers spluttering with laughter into their coffee at the very suggestion, but I’d still be interested to see what this technology would now look like with a decade and a half of development behind it.

The older I get the gladder I am that I’m not a really good racing driver. I can jump in most things and drive them reasonably quickly, but the difference between that and being so good that people want to pay you to race for them is considerable. The racing profession is like the acting profession, with far too much talent chasing far too few jobs.

Some are rich enough to pay to race, others to race for free, but most are not, and many end up instructing for not much money, trying to help people they’ve never met drive around race tracks as fast as possible. It’s my idea of hell. Many more simply give up the dream.

So when I race I do so for fun. I’ve been lucky to have been offered a number of opportunities over the years, but I’ve turned most down. However fast the car, however prestigious the series, the only question is, ‘does it sound like fun’, and if the answer is ‘no’, I’ll leave my suit on the hangar.

You may have heard the news that the next-generation Mercedes-AMG C-class is not going to be powered by a 4-litre V8, but a four-cylinder engine of half the size which, thanks to hybrid electric drive, will still produce numbers at least as impressive as those currently generated by the V8.

Talk about missing the point. You can buy a Casio wristwatch from Argos for £7.99 that tells the time just as well as a Swiss chronograph engineered by experts with devotion, passion and skills handed down the generations (in fact the Casio will actually keep far better time). But that’s not why people buy Swiss chronographs. And they don’t buy AMG Mercedes just because they accelerate fast in a straight line.

If, as I fully expect, this is a precursor to almost all AMG V8s being replaced by hybrid fours, I expect there also to be something of a backlash, just as there was when Porsche thought it a good idea to replace a six with a four in the Boxster and Cayman. I know there are good reasons behind such a decision – chiefly the need to drive down group emissions – but this is a hell of a price to pay. If someone asked me to name one thing I associate most with the AMG brand, it’s the thunder of a V8 engine. It gives that up at its peril.

A former editor of Motor Sport, Andrew splits his time between testing the latest road cars and racing (mostly) historic machinery

Follow Andrew on Twitter @Andrew_Frankel