Veteran to classic -- two GNs

Having re-acquainted myself with a fast Morgan three-wheeler recently, I thought it would be fun to do the same with a GN. Who better to approach than Edward Riddle, who…

It remains a statistical quirk that Italy produced two drivers who between them won three of motor racing’s first four world championships but has yet to conjure another, despite frequent strength in depth borne of the nation’s deep-rooted passion for the sport.

Take the 1980s…

It was a time when such as Michele Alboreto, Mauro Baldi, Ivan Capelli, Pier-Luigi Martini, Enrico Bertaggia and Stefano Modena showed sparkling form on the sport’s nursery slopes, yet only the first named would advance to become a grand prix winner. Alex Caffi was part of that potentially golden generation, but faded almost as quickly as he had flourished, his Formula 1 career over before he’d turned 28.

Caffi could have been forgiven for turning his back on the sport, but at 55 he’s still active, competing occasionally, running his own car and motorcycle racing teams and relishing every second.

“I’m still around,” he says, “because I absolutely love the sport.”

There was an inevitability about the direction Caffi’s life would take, because his father Angelo was a regular hillclimb competitor, as were two uncles, so he grew up amid sound and spectacle. “I began riding a motocross bike at seven and was racing from the age of 10,” he says. “I could perhaps have made that my career, but I was more interested in four wheels and transferred to karts at 16. I did that for just one year, then switched to Formula 4, an entry-level single-seater with a four-stroke Benelli engine and chain drive – almost a cross between a car and a bike.” He then graduated to Formula Fiat Abarth – featuring curious, wedge-shaped single-seaters in which most of Italy’s period hopefuls cut their teeth – and did well enough to land an Italian F3 seat for 1984.

Caffi won twice on his way to second in the championship – a result he repeated the following year – but the end of that campaign was to prove particularly significant.

The original European F3 Championship had been canned at the end of ’84 and replaced by a single, winner-takes-all event – in this instance at Paul Ricard. Caffi dominated from pole, earning himself an F1 superlicence in the process, although at the time he didn’t appreciate the full significance.

“Logically, my next step should have been F3000,” he says, “but I simply didn’t have a budget. I accepted an offer to remain in F3 [slipping to third this time], but then Osella needed a driver to replace Allen Berg in the Italian GP – and because of my Ricard victory I had the right licence.

“From the moment I started racing the only idea I had in my mind was to become a professional – my target was Formula 1, obviously, because that’s what everybody wanted to do, but I didn’t expect it to take only five years.

“I knew the Osella was uncompetitive, but that didn’t matter because it was the realisation of a dream. With hindsight, though, it was absolutely crazy. It was the turbo era – with maximum boost on ultra-soft tyres during qualifying – and even Osella’s Alfa Romeo engine was capable of producing about 1200bhp, at least for a few laps. That was less than the others had, of course, but still felt like a lot.

“Today drivers do endless simulator work and back then there was lots of actual testing, but I turned up at Monza on the Thursday, had a seat made and then went out during Friday practice with absolutely no previous experience. I did OK. I accepted that the car wasn’t quick and just tried to avoid mistakes – and to keep out of the way.”

He finished 11th, six laps down and unclassified, but was best of the Italians (the other seven all retired) and had done enough to earn a full-time Osella seat for 1987.

He would be classified as a finisher only once that year – 12th place, at Imola – because of a rule change. “The FIA reduced fuel allowance to 180 litres per race,” he says, “and right from the start we knew that the Alfa would be unable to last a full race distance. I ran dry with a couple of laps to go at Imola, but only lasted that long because I’d been driving deliberately slowly for about half the race.”

There were highlights, though, including 16th on the grid at Monaco, ahead of a Brabham, a Lotus, a Ligier and various other things that should not have been in his mirrors. On that occasion, the electrics packed up long before his fuel ran out.

Such flourishes did not go unnoticed. When wealthy Italian businessman Giuseppe Lucchini decided to set up his own F1 team – BMW Scuderia Italia – in Caffi’s home town of Brescia, Alex got the call. “There were other Italian drivers in the frame,” he says, “but Gian Paolo Dallara designed the car and put in a good word for me – he knew me from that F3 victory at Ricard, one of his company’s first international successes. It was also the first time I’d been paid to drive.”

Being a new team, and with 31 cars entered, Scuderia Italia was subject to the rigours of Friday morning’s 60-minute pre-qualifying session (the end of the weekend for those that failed to make the cut). Caffi performed well enough to be promoted above such hassles from mid-season and took a best finish of seventh in Portugal – before such accomplishments earned points.

In 1989 the team decided to add a second entry, which would be subject to pre-qualifying. “I had rather assumed that wouldn’t be me,” Caffi says, “but Andrea de Cesaris was in the other car, we were sponsored by Marlboro and he had good Marlboro connections, so…”

Caffi reverted to his pre-qualifying role, usually emerged unscathed and finished a career-best fourth in Monaco – but then came Phoenix, where he was on course for what would almost certainly have been third place until he was taken out while lapping a backmarker… who happened to be his team-mate. “Everybody could see what had happened,” he says, “but in the garage afterwards nobody said a word to him about what he’d done. I found that very strange.”

“There was no way Williams would pay my $1m release clause”

As the year wore on Caffi began to feel an increasing need to find a new home – and a stellar qualifying performance in Hungary, where he lined up third, put him firmly in the spotlight.

“That created a lot of interest,” he says. “Firstly, Marlboro summoned me to the McLaren motorhome, because Ron Dennis wanted to meet me. That was really just a chat – I think he was curious to know more about the guy who had been fighting Ayrton Senna for second on the grid. I had a formal approach from Lotus, but at that time the team was not as competitive as it had been. I came to England to talk to Flavio Briatore and Rory Byrne, at Benetton, but my really, really big chance was with Williams. I met Frank Williams and Patrick Head in their motorhome at Monza, but my contract with Scuderia Italia contained a $1 million release clause – and there was no way a team like Williams was going to pay that when it could have chosen almost any driver on the grid.

“Footwork was happy to pay it, though – and at the time it seemed like a good option. I was offered a two-year deal and they’d shown me a contract to confirm that Porsche was coming on board to supply engines. I might be Italian, but my father always liked Porsches rather than Ferraris and I had grown up around that, so for me the chance to drive with Porsche was a bit like racing with Ferrari would be for most Italians.

“Porsche hadn’t been in F1 for a few years, but its previous [TAG turbo-branded] engine had won everything with Niki Lauda and Alain Prost at McLaren, so in my mind I was going there to challenge for the world championship.”

After an interim campaign with Cosworth (when he again scored his best result in Monaco, this time fifth place), on-track development of the new Porsche engine began during the winter of 1990/91.

“I felt the team was using me to deflect from its own problems”

“It wasn’t immediately apparent that the engine wouldn’t be competitive,” Caffi says, “because in the first test at Silverstone it blew up on its third lap, so I didn’t learn very much. But we soon realised that it had lots of power at the top end but hardly any torque – and the worst thing was the weight. It was about 40kgs heavier than a Ferrari or a Honda, a bit like driving a 911 with all that mass at the rear…”

He failed to qualify for the opening four grands prix – and split his car in three when he crashed while trying to wrestle it into the race in Monaco, although he escaped without injury. A few days later, however, he was out with friends in Italy when he was involved in a serious accident that left him with a broken jaw.

“I was a rear-seat passenger,” he says, “but I got a lot of criticism because the team said I shouldn’t have put myself in that kind of situation. I had a feeling that the team was using my situation to deflect attention from some of its own problems.”

By the time he returned, Porsche had gone, Footwork had reverted to Cosworth and he endured a string of non-qualifications before achieving a couple of modest results in Japan and Australia. “I’d really had enough of all the F1 politics by then,” he says. “I’m a simple soul, really, and just wanted to get on with racing.”

For 1992 he was offered a seat by the new Andrea Moda team, but he walked away after a single test – “It wasn’t as though I’d been driving for McLaren,” he says, “but I had been with solid, well-structured teams and this was just a mess” – and little more than two years after being courted by Williams, his F1 career was over

He spent part of the summer with Mazda, racing in Group C – “I really enjoyed that, but they killed off the championship just as I was getting started” – and then took a 12-month sabbatical while wondering what to do with himself next.

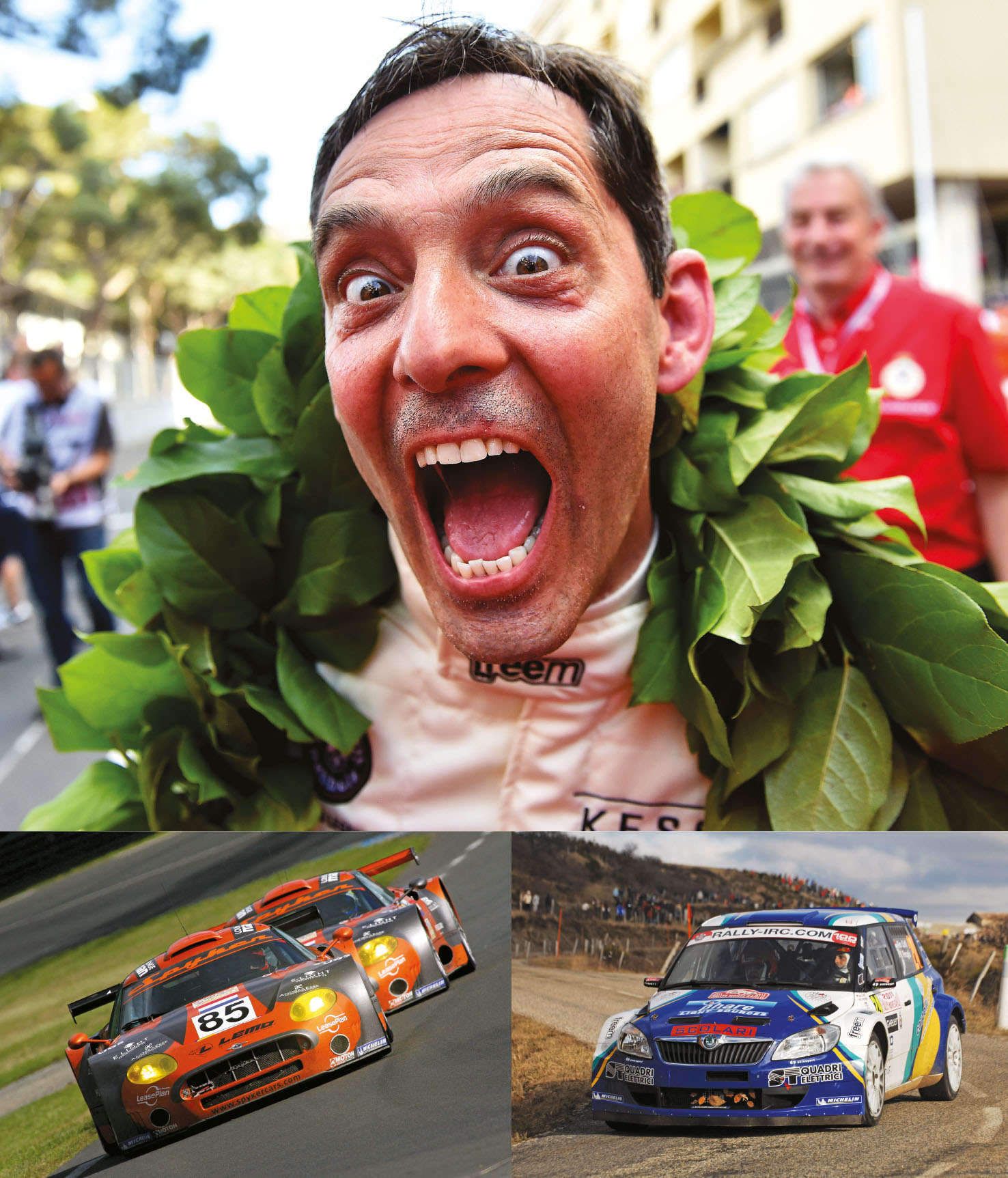

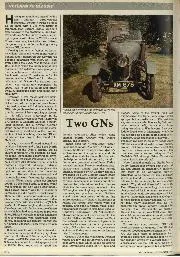

“I realised that I didn’t know anything else,” he says, “and just decided to race whatever and whenever I could.” Thus began phase two of his career, an enduring cycle of sports and touring car races with occasional diversions into alien territory. He has contested the Daytona 24 Hours, Sebring 12 Hours, Le Mans (three times, sharing the sixth-placed Courage in 1999), taken class victory in the Spa 24 Hours, won GT titles in France and Italy, guided a Škoda Fabia to 11th overall on the 2011 Monte Carlo Rally and contested successive Dakar Rallies in a Fiat Panda 4×4… then a Unimog-Mercedes truck. In 2016 he took Ronnie Kessel’s Ensign N176 to victory in the GP de Monaco Historique and in recent seasons he has developed his own team, Alex Caffi Motorsports, the main arm of which runs in EuroNASCAR.

“You know,” he says, “I really believe that if Porsche had produced a good engine at the right time then my career could have been very different, but I have no complaints. My proudest achievement has nothing to do with F1, though. In 2011 I entered the Trofeo Vallecamonica hillclimb, an event my father had won in 1965, at the wheel of an Osella FA30. F1 is incredibly safe nowadays, but events like that… trees on one side, ravines on the other. Drivers are risking their lives for no reward. Nobody knows who they are, they do it for the challenge – it’s a bit like the Isle of Man TT for cars, the essence and soul of our sport.”

He completed the course in 7min 26.6sec, a record that remains unbroken.