Brough buff

Sir, Come on M.L. have you been really fair to George Brough in your article about his cars and bikes? You say he was not the engineer he was "usually…

Karl Ludvigsen

Published by Delius Klasing, £14

ISBN 978-3-667-11457-0

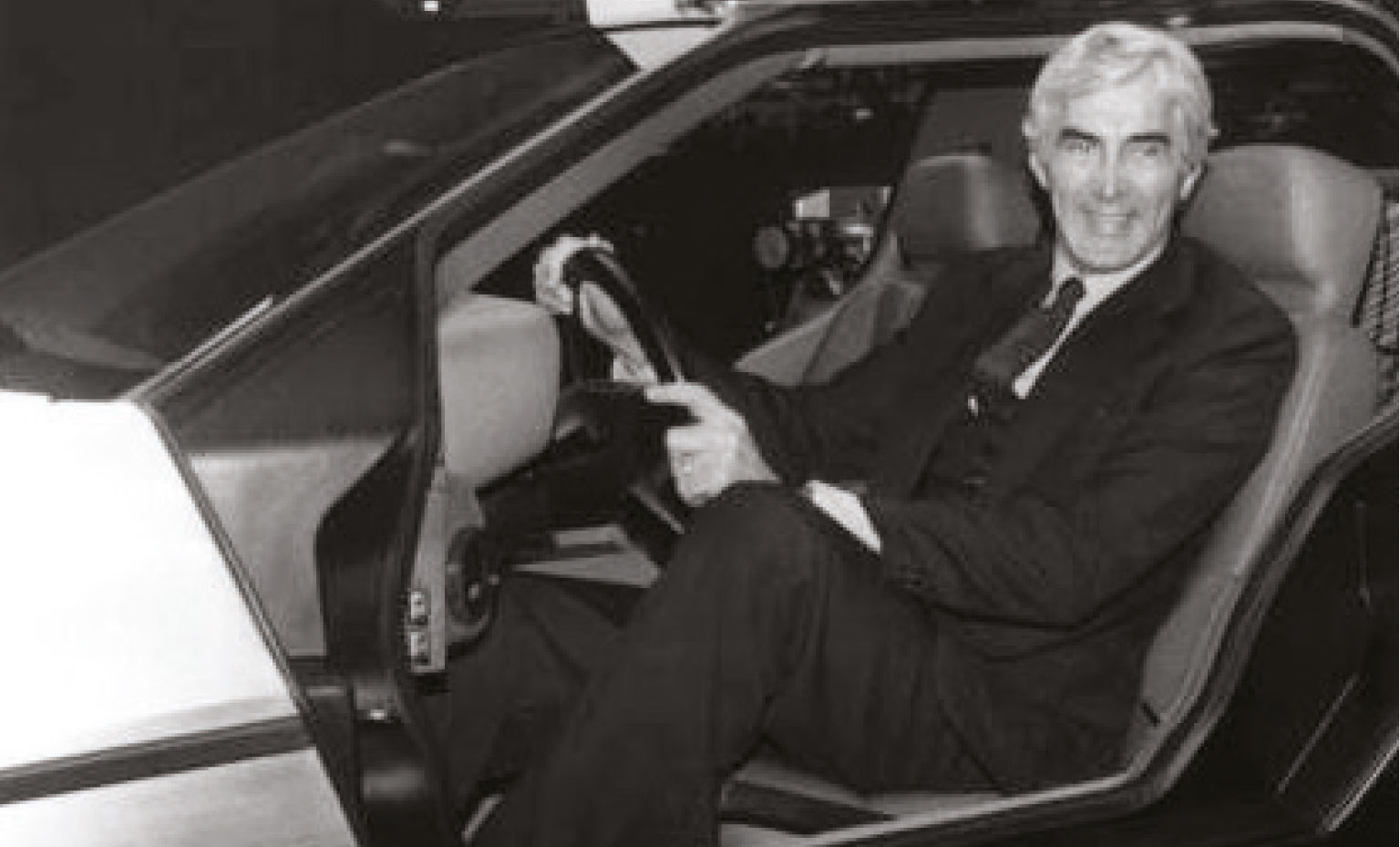

During a lifetime in the motor industry as both an executive – a vice president of Ford – and a consultant to among others GM and John DeLorean, Karl Ludvigsen became prominent through his extensive photographic and factual archive, as a journalist, and through his writings as a historian of cars and racing. With some four dozen titles behind him he has established himself as a painstaking researcher with a deep understanding of the engineering of both manufacturing and racing cars.

In his five decades in the industry he has met, worked with and befriended many of the key figures in both aspects of the business, and it is his recollections of 23 of these which he has assembled into this book. Some were indeed ‘fast friends’, and some colleagues and associates, but all are people Karl knew, and though not all the pen pictures are first-hand – he draws on other memoirs, too – they are all informed by personal contact.

The subtitle Stars and Heroes in the World of Cars is a valid distinction: among the famous characters – John DeLorean, Giorgetto Giugiaro, Phil Hill – there are also people who influenced the industry but whose names are scarcely remembered, such as Stefan Habsburg, who shaped GM’s design in the 1950s and beyond. (Karl adds that Habsburg was technically an Archduke and a descendant of Queen Victoria!)

Divided into Executives, Designers, Engineers, Racers and just plain Car Guys, his list starts with his own father, who fed his interests in engineering and design, before jumping in with Ferry Porsche, whom he knew from the 1950s. “It was fascinating,” he notes, “to discuss Porsche’s affairs with a man who had driven the Auto Unions and shaken hands with Hitler”. Ludvigsen is known for his research into the German motor industry and discussions with Ferry Porsche were a major part of that. Some of it appears here, such as that during WWII Porsche schemed a small V10 sports car “so we would have something to do after the war”, and that they quietly kept improving the Volkswagen design during WWII by describing upgrades as ‘for military use’. When Ferry muses on the company’s history, Ludvigsen remarks “that was typical Ferry, second-guessing past decisions” – the sort of shading you don’t get from a simple marque history.

He continues with a portrait of Ferry’s sister, the powerful Louise Piëch, who ran Volkswagen distribution in Austria and was the mother of Audi/VW Group leader Ferdinand Piëch. It’s a complex history but the remarkable Louise had an immensely profound effect on keeping the family businesses together. She memorably claimed “I have only ever driven my family’s cars: first those of my father, then those of my brother, and now those of my son”.

Although the book is concerned chiefly with people, there’s plenty to learn about machines too, about the various incarnations of Mercedes C111 and a stillborn early ’50s project from the aforementioned Habsburg for a GM front-drive machine with CVT and a rear wing/airbrake.

Elsewhere in this issue we describe the pretty little BMW 1602 (see page 142); that car thrived because of another man pictured in the book, Alex von Falkenhausen, whom Ludvigsen calls “BMW’s engine Pope”. Racer, engineer and later head of BMW motor sport, von Falkenhausen conceived the tough little four that powered the Neue Klasse cars which founded a new chapter for the firm, and that same basic engine went on to produce the mad 1200bhp of the turbo F1 years, garnering a driver’s title in a Brabham. Alex von F also expanded it into the famous six that brought so many race successes, so this is a prime example of what this volume does well – a brief portrait of someone whose significance might be overlooked.

“When The Telegraph headed DeLorean’s obituary ‘Dodgy car manufacturer’ I knew it was cut-down time”

In contrast, we’ve all heard of John Z DeLorean. Ludvigsen classes him as engineer rather than an executive, citing how he revitalised Pontiac and Chevrolet in the 1970s. Ludvigsen was an advisor to John Z after he left GM, so it’s no surprise that he is sympathetic to a man whose media legacy is not kind. “When The Daily Telegraph headed its obituary ‘Dodgy car manufacturer who relieved successive British governments of £78m of taxpayers’ money’ I knew it was cut-down time,” he laments. I can’t say I know enough about the affair to either fire or deflect bullets, but even if it does rather gloss over the cocaine sting this chapter is a rare balance to the popular view of a man who was undoubtedly a marketing visionary.

Drivers included are Fangio, Emerson Fittipaldi, Mario Andretti and Phil Hill, with all of whom Ludvigsen had at least some connection, Hill especially. Reporting his racing as a journalist from 1957 on, Karl was there in 1966 as the laid-back Chaparral team got the 2D coupé ready at the Nordschleife “with a lethargic casualness that frustrated the tightly wound Hill. ‘Don’t you guys realise this is the goddamn Nürburgring?’ he exclaimed”. From his own book on Fittipaldi comes the Brazilian’s memory of his maiden win at Watkins Glen in 1970: “I had seen photographs of Chapman throwing his hat in the air for Jimmy Clark, then Graham Hill and Jochen Rindt. And now it was for me. When I stopped at the pit I couldn’t remember a word of English!”

While none of the sections pretend to offer complete biographies, they shine a worthwhile light on his choices, with many nuggets to be found – including that Rudi Uhlenhaut was born in Muswell Hill!

For the latest motoring books, visit Hortons Books