In the wild world of stock car racing in those days many small, regional sanctioning bodies promoted their own races, often in direct competition with each other. Most of these little groups, NASCAR included, were considered outlaws by the AAA (American Automobile Association), which had ruled all American motor racing since the first decade of the century with the Indy 500 as its unrivalled centrepiece.

In May 1955, France – the ‘outlaw’ stock car promoter – was thrown out of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway’s Gasoline Alley by AAA officials. France was wearing a borrowed garage area credential and some AAA people spotted the ‘outlaw’ promoter with his illegal credential and asked the chief steward to escort him out of Gasoline Alley.

France always maintained that it was the AAA, and not track owner Tony Hulman, who had thrown him out of the IMS’s garage area. Hulman and he were always on good terms, France insisted, but it was an interesting day in the life of the man whose organisation would ultimately, after his death, stage the biggest annual race at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway – NASCAR’s Brickyard 400 in August each year – and whose own Daytona 500 would far outstrip the Indy 500 in TV ratings, prestige and commercial value.

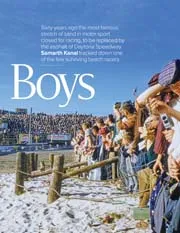

Building work in ’58

ISC Archives via Getty Images

Less than four years after his embarrassing moment at Indianapolis, France was fully occupied launching his new superspeedway. Fireball Roberts and his peers immediately showed that the high-banked track would produce speeds for NASCAR stock cars that were equal or better to those turned by Indy cars at the comparatively flat, four-cornered Indianapolis oval. And as practice, qualifying and the preliminary races took place for the Daytona International Speedway’s first ‘Speedweeks’ it also became clear that the track would produce a new and exciting kind of spectacle. It would earn the nickname ‘drafting’.

Legend has it that Junior Johnson discovered the ‘draft’ at Daytona a few years later but the truth is all the top drivers experienced the ‘draft’ during practice for the first Daytona 500. They discovered their cars would pick up speed while running in the slipstream of a car or pack of cars ahead and with the right timing you could pull out and ‘slingshot’ ahead of your competitor. Running at sustained speeds they had never previously experienced the drivers tried to understand the phenomenon better and take advantage of it in the race.

The first race at Daytona was run on February 20 1959, two days before the inaugural 500. The track’s maiden race was a 100-mile event for open-roofed ‘convertibles’, followed directly by another 100-mile race for ‘hardtop’ Grand National cars. The convertible race was won by ‘Shorty’ Rollins, who drafted past Marvin Panch and Richard Petty’s cars on the run off Turn 4 down to the chequered flag. The Grand National qualifier was won by Bob Welborn’s Chevrolet from Fritz Wilson’s Ford Thunderbird.