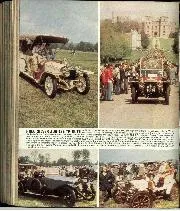

RREC Silver Jubilee Tribute

A breathtaking collection of some 500 pre-World War Rolls-Royces assembled at Windsor Castle on May 7th for inspection by Her Majesty the Queen, a tribute to her organised by the…

CARS AND THE GRADUAL INFLATION THEREOF:

THE mechanical evolution of the car has often been dealt with: in the

first year or two of this century design settled down to one basic pattern that has persisted in broad outline ever since, with ostensibly minor internal changes which have, nevertheless, profoundly affected performance. There is another hitherto neglected but equally striking evolutionary phenomenon that we may call inflation.

From 1890-1905 three trends are specially noticeable ; cars became lower, longer and plumper. The first vehicles that can legitimately be called cars were frail and spindly. They and their immediate successors have been described as resembling the Holy City, in that their length and their breadth and their height were approximately equal. (This has also been said to be still true of London taxis—unfairly, because much of their height is light superstructure.) Gradually becoming lower for the sake of stability, and acquiring larger engines for the sake of performance, a longer wheelbase and more robust wheels were called for. The lowering and lengthening process was accompanied by the fitting of smaller but fatter tyres and a general rounding of contours, which gave some of the open tourers of 30-35 years ago a good appearance judged even by modern standards. This state of outward development—comprising a very slight rear overhang, radiator (or the front edge of the bonnet if the radiator was behind the engine) roughly over the front axle, and wings that allowed easy access to the axle ends—persisted for a couple of decades.

An Aspect of Evolution

The last trace of skinniness went when balloon tyres were adopted and front brakes became universal. This was the period that, in the opinion of many, produced our finest cars, the mid-nineteentwenties vintage. From the point of view of appearance, ears had now fattened out to that pleasant-but-not-too-plumpness that is admired by students of most kinds of form. The worst blemishes were the introduction of imitation fabric bodies that killed the genuine Weymann flexible construction, and the unaccountable popularity of the dummy hood iron. Unfortunately this delectable state was short-lived. First the engine was moved forward, making possible the mounting of roomy bodies on short, unwieldy chassis, but also calling for more rear overhang to restore a balanced appearance. Mechanically, forward engine-mounting was probably a worthy move, but it led quite unnecessarily to some astonishing :esthetic misdemeanours—such as ornate radiator grills where light stone guards would have been equally effective, bulges in unexpected places, euphemised as streamlining: curiously swollen wings and connective fairings that enveloped the wheels and evoked prayers for tinopeners whenever the axle extremities

needed routine attention. Even sports cars with no unsightly bent-gaspipery to hide have not been wholly immune from this galloping elephantiasis, though the stage that a normally-staid contemporary has described as the “slug motif” of design—” a large slug in the. middle with four smaller half slugs stuck on at the corners “—is mercifully rare. The slugward development, which is neither beautiful nor useful, is the original inflationary process run riot, as if a normal car had been over-distended like a child’s indiarubber pig that has been blown up too far. The lost msthetic appeal will only be regained by deflation to natural proportions.

‘Happily, inflation cannot go on indefinitely. Beyond a certain stage either the bulges overshadow the car or else the outline becomes so smoothly balloon-like that even the drawing-office is shocked into moderation. I am inclined to agree. with W. S. Renwick: “Cutting off the rear overhang drastically, and cutting off. the ‘false nose,’ represent a much closer approximation to the shape of cars to, come than has been suggested by other prophets.”

Incidentally, I wonder (1) why an appreciably projecting semi-streamline tail looks so awful on anything but an open 2-seater, where it can look quite pleasing if unfinned, though its utility is still questionable and its vulnerability nightmarish, and (2) whether it is too much to hope that some day the mere smoothing of contours, desirable though it may be, will cease to be called streamlining ?—J. D. E.