How Williams improved its FW43B: Giving the underdog its day

After years of struggle Williams is again looking a competitive F1 team. Here’s how it turned a pig’s ear of a car into a silk purse

Williams scored its first podium since 2017 with the FW43B, albeit thanks to a bit of fortune in Spa

Xavi Bonilla / DPPI

Illustration by Craig Scarborough

In Sochi George Russell qualified the Williams FW43B into Q3 for the third time this season. Once there, an inspired early switch to slicks played its part in his sensational third place on the grid. Russell is clearly operating at an extremely high level and the car is in reality still only a marginal Q1/Q2 runner most of the time, but it’s good enough that a just slightly favourable set of circumstances can allow Russell to produce these occasional shock outcomes (see also Silverstone and Spa). Given that the basic architecture of the car is still that of the disastrous 2019 FW42 clearly big advances have been made within that limitation. In ’19 Williams hung off the back of the grid by a significant margin; in 2020 it was able to compete with Haas and Alfa-Romeo. This year it has left Haas well behind and can on occasion mix it with more exalted company.

The technical management of the team has steadily improved and this has continued under team boss Jost Capito’s recruitment of his former VW colleague Francois-Xavier Demaison as technical director. But given that the late-notice Covid-inspired regulations of 2021 insisted on the existing 2020 base cars being used, the continued improvement has been noteworthy.

That stipulation ensured a built-in limitation to the ’21 car – that of its wide nose. By last year this had become an unfashionable feature as Red Bull, Renault, McLaren and others all transitioned to the Mercedes-inspired needle nose. It allows the under-nose cape to turn the airflow much earlier and more effectively towards the barge boards, which then direct the airflow between the underfloor, body sides and outwash. But Williams was stuck with it, given that it had chosen to spend its development token elsewhere.

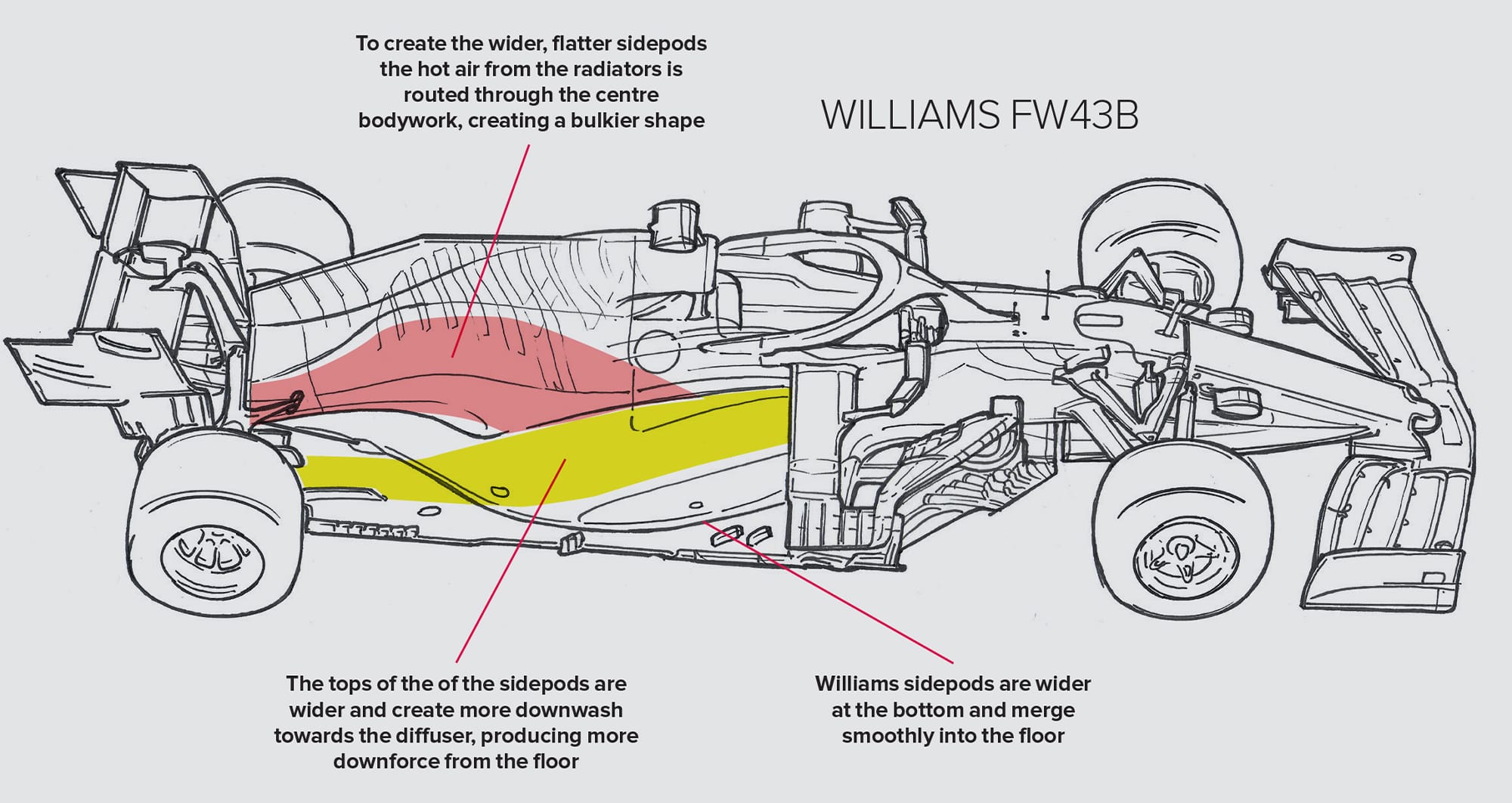

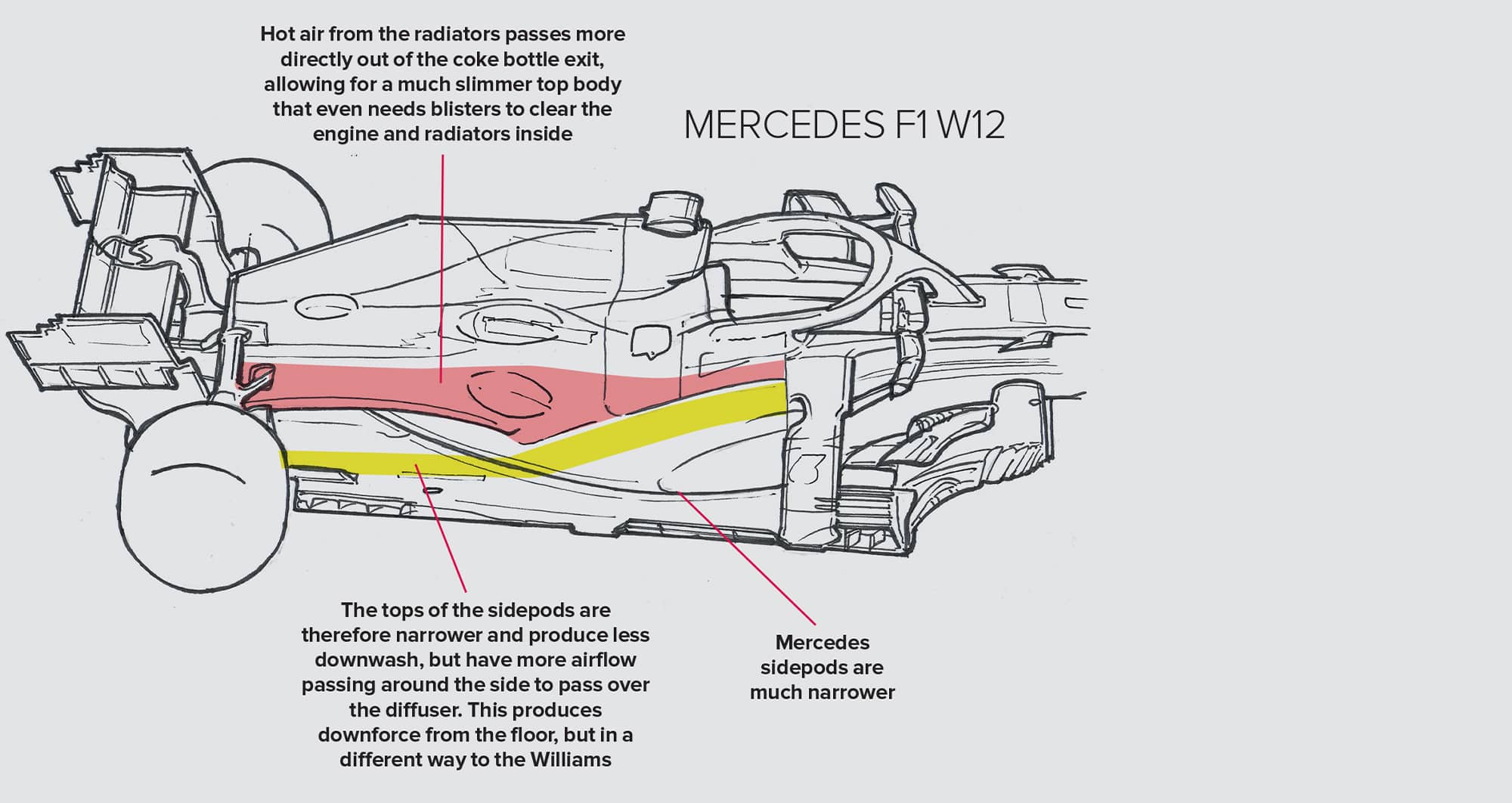

Williams vs Mercedes

When compared side by side the design differences between the front-of-the-grid Mercedes and the Williams become clear. While the Silver Arrows design has pioneered a ‘size-zero’ concept, the Williams is much bulkier in comparison. However, thanks to concentrated development on the airflow around and through the rear coke bottle section, Williams has managed to find significant gains this year.

It was probably partly in compensation for this limitation that Williams opted for a very different radiator air cooling route which, in comparison to the identically-engined Mercedes and Aston Martin, made for a much bulkier lower engine cover but an enhanced coke-bottle section of the lower bodywork (so named because of the similarity in shape to the top of the classic coke bottle).

As can be seen from the drawings, Williams has taken the air cooling passage up high and over the camshafts and exhausts in contrast to the straighter, lower route chosen by Mercedes. This has significant aerodynamic implications for the design.

“The coke bottle creates a pressure change in the airflow”

The coke bottle section, first employed on the McLaren MP4/1 of 1981 and now a universal feature of any F1 car, creates a pressure change as the airflow makes its way along the lower body, effectively sucking it along faster. The faster it can be made to flow over and around the diffuser, the greater the contrast between its pressure and that of the underfloor airflow – thereby inducing the underfloor to suck down harder.

In opting for this cooling route for the 2021 car, Williams created the opportunity for an enhanced in-sweep of the coke bottle. This potentially could offset the limitation of how much airflow the wide nose allowed to be directed there.

But, as ever, there are complications. If the in-sweep of that coke bottle section is too extreme and the airflow feeding it not strong enough, the flow can stall, thereby reducing the pressure difference between the upper and underfloor airflow and therefore downforce. An aggressive in-sweep in combination with a wide nose is indeed quite ambitious, but Williams felt it would rather have an over-sensitive car which could sometimes be quick than a less sensitive one which never would be.

As such it has tended to be highly sensitive to crosswinds. It is also at its best on longduration corners rather than through short, sharp ones. As a consequence, much of the development applied to the car through the season has been trying to enhance the feed to that coke bottle section – and that starts right at the front of the car. Reduced-diameter front brake ducts from round two in Imola allowed more of the front wing’s wake to be out-washed aside. Aerodynamicists are always seeking to push the disturbed air from the front wing and wheel as far out as possible so that it does not interfere with the flow down the body sides and underfloor. This will be extra important to a car needing a more robust airflow to feed the coke bottle.

Extra barge board flaps beneath the ‘boomerang’ vane appeared at Baku, trying to energise the flow downwards and along to the lower body and coke bottle, together with a revised arrangement of vanes ahead of the rear wheels.

Although none of these development directions will have a direct relevance to the all-new regulation cars of 2022, the progress Williams has made with this car despite its built-in limitations bodes well for the team’s future going forward.