Al Unser Jr: Fall from grace

Al Unser Jr was IndyCar royalty even before he won the 500, but as his newly published memoirs reveal, off track his life was spinning out of control. He tells Damien Smith how he has finally made peace with his past

Not too many motor sport autobiographies begin with the protagonist pointing a gun at his own head with the genuine intention of pulling the trigger. Nothing about A Checkered Past is normal, especially in the context of straight-up and serious racing books.

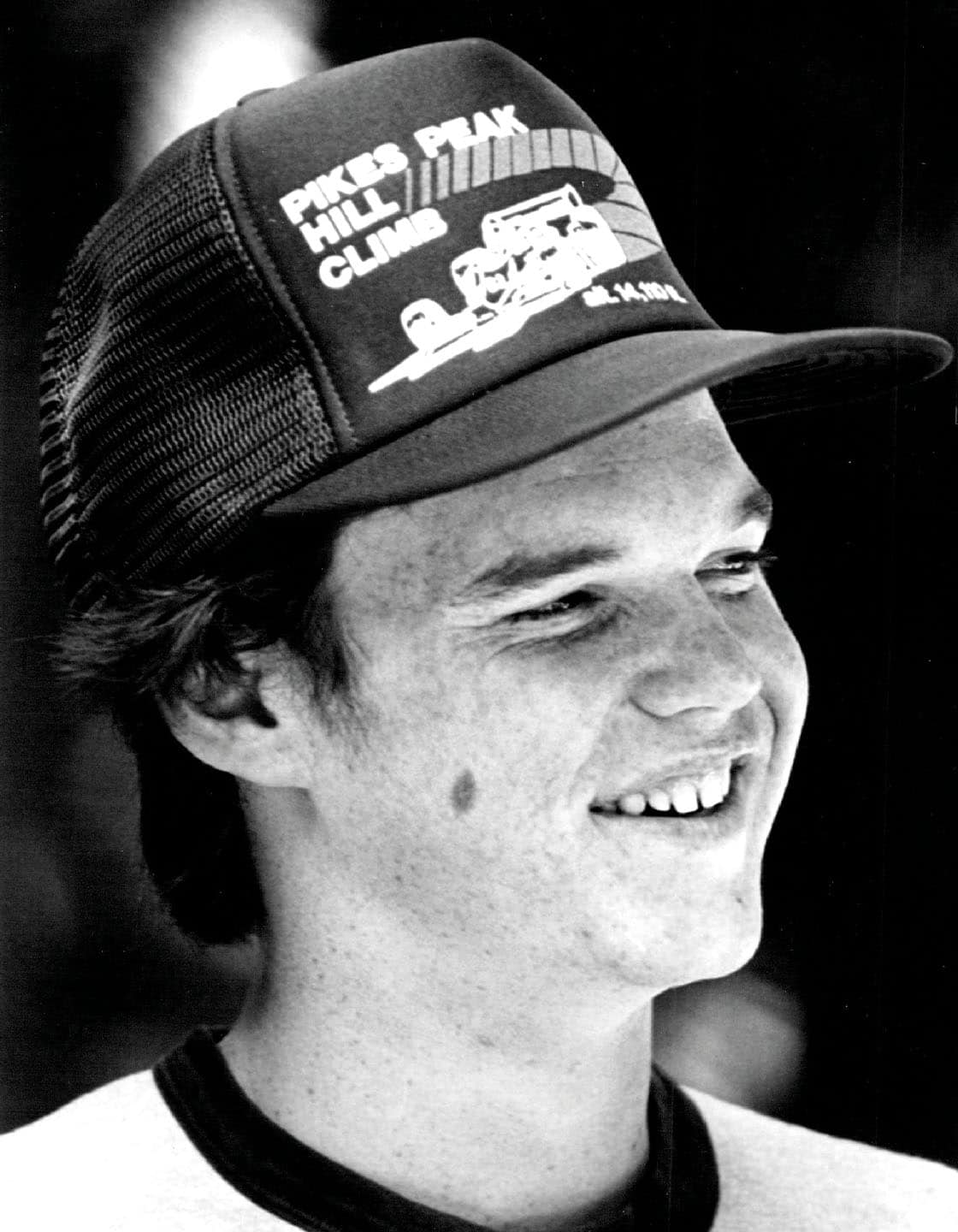

Then again, the same can be said of Al Unser Jr. Born into one of the great American motor sport families, ‘Little Al’ followed in the best traditions of his namesake father and uncle Bobby to become an IndyCar legend. But he also created a few less illustrious traditions all of his own, in a double life that was dominated and almost destroyed by drug addiction and alcoholism.

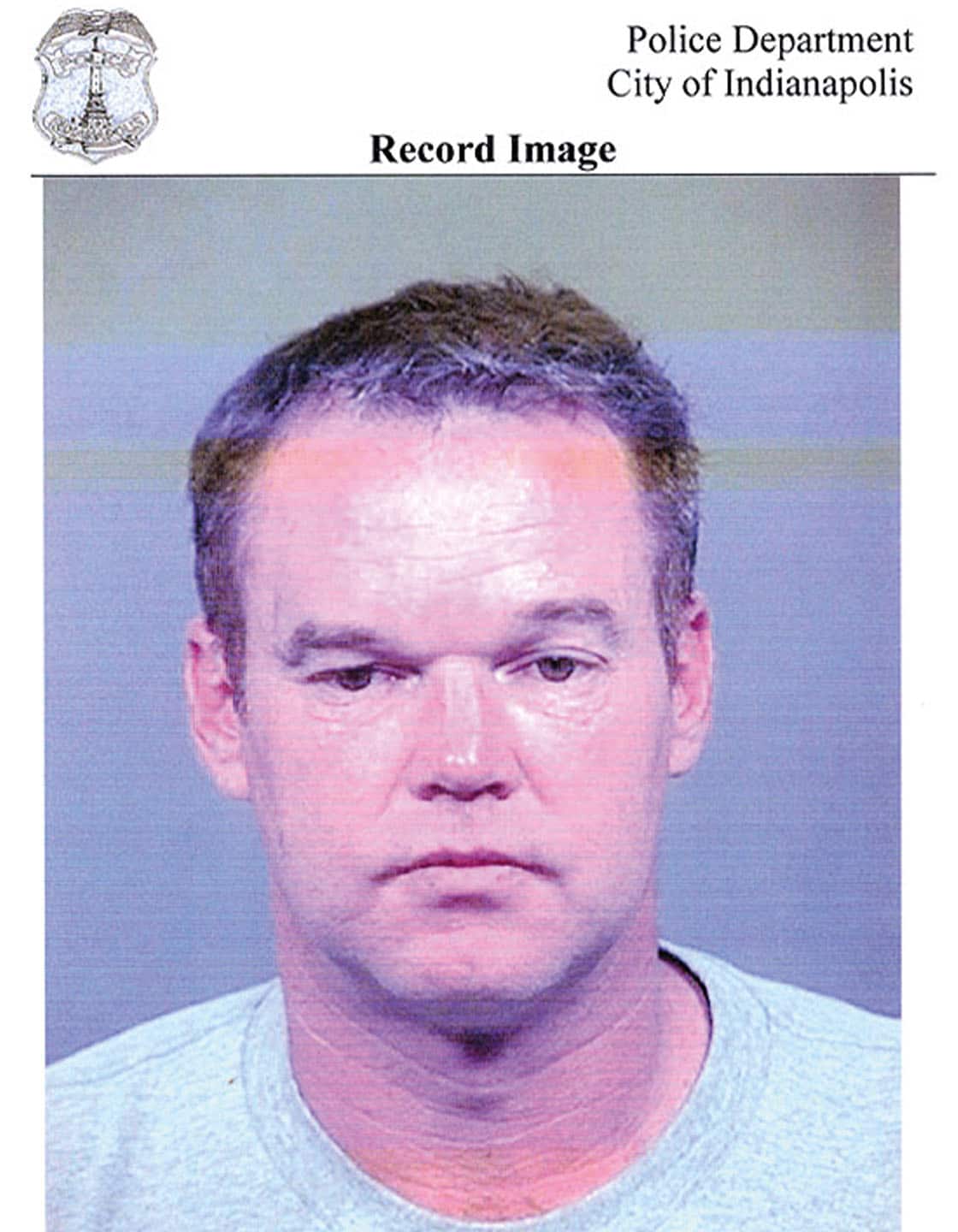

Inside the IndyCar paddock, it was an open secret from early in his stunningly successful racing career that Unser Jr liked to “party”, as the Americans so quaintly put it. But it was only in the past 20 years that the two-time Indianapolis 500 winner’s life spiralled out of control and spilled into the public glare. Arrests for drink driving and domestic violence lifted the veil and shocked an IndyCar fanbase that places its heroes on high pedestals, as the life and career of an increasingly puffy-looking Junior dwindled into sad, sponsor-less obscurity.

“His arrests lifted the veil and shocked IndyCar fans”

From drinking the milk at The Brickyard, winning a pair of IndyCar Series titles and 34 premier-class races, scoring back-to-back Daytona 24 Hours victories in Al Holbert’s Lowenbrau Porsche 962, beating NASCAR greats at their own game in IROC (twice) and even conquering Pikes Peak’s ‘Race to the Clouds’, by 2004 Little Al had been reduced to a bad joke. One that absolutely wasn’t funny.

But only now through his new book do we learn the depths he was brought to by an illness – and lest we forget that’s exactly what it is – that gripped him for four decades, even during his glory years of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Little Al lays it all out, describing in unflinching detail a tragic existence that cost him two marriages and left lasting and perhaps irreversible damage to his relationships with his four children. The book is packed full of fantastic racing stories too, offering all the insight you would hope and expect from his rich and varied career. But it’s the personal decay and destruction at the heart of this story that will linger most. It’s a brave and astonishing piece of work in its unflinching, brutal honesty.

On a Zoom from his home in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Unser looks well, that familiar open smile beaming across the Atlantic beneath a plain flat cap. The voice is rich, slow, higher than you expect and warm like pancake syrup, and infused with those traditional southern manners. His ghost writer Jade Gurss described the book as like The Wolf of Wall Street on wheels. How does he see it?

“I’ve actually been a little bit scared about the whole thing because I’ve been so honest,” says Unser. “I haven’t had anybody read it so far outside of my family. You’re one of the first. I was having dinner with my mom last night and she was asking me, ‘Are you excited about the book?’ I looked at her and I shrugged. I don’t know because I haven’t had any feedback yet from the outside world.

“The goal is to really help people. I hope that whoever is afraid of asking for help is not afraid of doing so after they read the book. As far as the racing fraternity is concerned I feel there are going to be people who after they read it go, ‘Wow, I didn’t know that was going on in his life.’ It will be a bit of a shock. Others will go, ‘Oh yeah, that makes sense now.’” He chuckles, as he does throughout the conversation. “It’s in God’s hands.”

Unser pays full credit to Gurss, author of the late John Andretti’s fine book Racer and also Beast, the excellent re-telling of Penske’s 1994 Indy campaign with the pushrod Mercedes-badged Ilmor engine that tore through a rules loophole and powered Little Al to his second emphatic victory at the 500. Their first Zoom call stretched to six hours, Junior reveals, during a process he admits was “therapeutic” and that took him through “a rollercoaster of emotions”.

Little Al from Albuquerque: born into one of America’s great racing families, fresh-faced Unser Jr paid his dues in karting and sprint cars, then won titles in Super Vee and Can-Am

It seems he felt compelled to tell his story, probably against the wishes of his father and Uncle Bobby, who died earlier this year aged 87. Al has also lost his cousin Bobby Jr in recent months, compounding what has been a tough year for the Unsers. Now this…

“I sent my dad a copy of the book and um… I haven’t heard back”

“Uncle Bobby and Dad wanted to maintain a certain image so I had to keep a lot through my life away from the public,” says Unser of a family that share nine Indy 500 wins between them. “With my arrests and so on it got out there. If anyone was to look down on me, it was my dad and Uncle Bobby!” He says this with a big smile and another chuckle. “It was actually during the Covid thing the world was going through when I decided to write the book, to be as truthful as possible and put it out there.”

Has Al Sr, now 82, read it? “I sent my dad a manuscript when it was first done and um… I haven’t had any feedback from him. I don’t know what his thoughts are on it.”

Sr and Jr went head-to-head in 85. Dad won the title, by a point

His portrait of Unser Sr is a long way from flawless. Junior’s parents divorced when he was young, Al citing his father’s infidelity, and he describes how he was “raised by Dad’s belt”. But there’s also a lot of love and affection directed towards the four-time Indy winner too. “I look at my childhood and it was really good,” Al tells us. “I had great parents, and even though they divorced they were always there for me throughout my life. Yes, I was raised with a belt” – there’s that chuckle again – “but everything my dad did was for the betterment of me. He didn’t know any different because he was raised by a belt. He did the best he could and quite honestly he did a great job. Dad definitely has a heart because although he was hard on me, by the end of it he was there for me. He is today.”

Unser describes “two Al Jrs” existing through his life: the professional racing driver who was fully focused at the tracks and got the job done; and the car wreck behind closed doors, who lacked self-esteem and turned to marijuana, cocaine and alcohol to get through the slow days. Somehow he and first wife Shelley, whom Al married in 1982 aged just 19, kept their shared hedonism mostly between four walls.

There’s some fascinating insight into his troubled state of mind from the racing stories. After an apprenticeship served in karting, Super Vee, an ill-starred spell in sprint cars and a much more positive experience in Can- Am, Little Al made his IndyCar debut at Riverside in 1982, driving for Rick Galles on a grid that included AJ Foyt, Mario Andretti, Gordon Johncock and his dad. In other words, his idols. Through attrition, he finished fifth that day in California, and beyond the initial euphoria a strange reaction set in. “I was truly depressed,” he writes. “The immortals had become mortal. They were racing legends carved in stone. But now? Only men. Flesh and blood. To me, it was profoundly sad.”

“I was surprised that I was depressed because I did have a great debut at Riverside,” Junior tells us. “I was racing against Dad and all these legends I had on a pedestal and just to be able to race with them was itself a great thing. But I was let down: it just proved they are men, just like myself and yourself. And that folds into my dad telling me ‘the Indy 500 is just another race!’” Big laugh at this. “What? Are you kidding? It’s not just another race. But when you get to reality, that’s what it is. I’ve been witness to Juan Montoya doing interviews when he says, ‘Hey, there ain’t nothin’ special about this place. You just go out there and treat it like it is.’ He’s right. However, it is the Indy 500.”

The Brickyard is a lifeline through Al’s story. “Jade’s impression of the book is that it’s my love story for the Indy 500,” he says. “It just shows the love I have for the place. When you are in the groove and everything is going good for you, it’s heaven. Because it didn’t happen that often. I ran the race 20 times and there was only three or four that were actually fun and enjoyable. The rest of them… shit, I’ve gotta wait a whole year to come back.”

His telling of the first 500 win, for Galles/ Kraco in 1992 and at the 10th time of asking, is spine-tingling, especially how he held off Scott Goodyear in a dash for the line where just 0.043sec separated them. But as is so often the case, it’s the losses that stick out more. His defeat in 1989 to Emerson Fittipaldi, who stuck him in the fence on lap 198 of 200, is one of the most heartfelt and dramatic accounts of a race climax ever written.

Junior scored back to back wins in the Daytona 24 Hours in Al Holbert’s Porsche

“1989 was a heck of a year. I still consider that race truly my best drive, in all the years that I competed at the Indy 500,” he says. “And the team [Galles/Kraco]– nobody made any mistakes. It was calculated all the way. As a matter of fact if that last yellow flag hadn’t have happened, we were cruising to a 30sec victory over Emerson and I would never have had to race him at all. That’s how well-planned out that whole race was, with the soft compound tyres. It was all what my father was saying: just get to the end, there’s only one lap you want to lead and that’s the last one. It was my seventh year at Indy, it was going perfect and we didn’t show our hand until the end. When I was going down the back stretch and [slower] cars had wrecked my momentum, Emerson was able to get up alongside me. But once we got halfway down that straightaway I started pulling away from him. Well alright!”

It was your corner, we say… “Oh yeah. And then Dad came into the hospital saying, ‘You can win this race.’ I’m like, ‘What are you talking about? He’s drinking the milk!’” Al Sr was pushing his son to protest but Junior didn’t bite. “I had never been to Victory Lane with my dad’s four wins. I was supposed to be there in 1978 with my sisters, and I got in trouble for dipping school so I was grounded!”

Unser Jr hits the wall as Fittipaldi heads for Victory Lane

Perhaps the defining image of his career is Al Jr standing next to the track giving Fittipaldi a handclap and double thumbs up as the Brazilian celebrated his first Indy win. Junior won plaudits around the world for his sportsmanship, although as he tells it in the book, his intention as he walked out there was to “flip him out” (the handclaps do look sarcastic). That crash hurt him a lot more emotionally than it did physically, and yet his strong friendship with Fittipaldi survived. “Well, it was Emerson,” he says. “He has a certain aura around him, like Mario Andretti. Emerson is a man of kindness and true care for his fellow drivers. If it was somebody else in 1989 maybe there would have been a different reaction. We’d already been close friends. For example, he’s godfather to Shannon, my second daughter, and that happened prior to 1989. We are still very close to this day.”

The pair shared a great deal more as teammates when Little Al finally achieved his life’s ambition of signing for The Captain, Roger Penske, in 1994. After the landmark victory for ‘The Beast’ that season, the pair experienced what remains an unbelievable low in 1995 when the Penske drivers sensationally failed to qualify for the 500. The rules loophole had been closed, but even with standard Ilmor power the Marlboro cars should have been in the mix for the win. Instead, their month of May unravelled, the team even switching from its own chassis to a Reynard, before Al made a desperate lastditch attempt to make the cut in one of Bobby Rahal’s Lolas. The growing sense of anxiety in those weeks is a key chapter, Junior describing it as the moment when the two Als began to converge.

‘Al Unser Jr’s Turbo Racing’ for the Nintendo Entertainment System was launched in 1990

“It was the first time I really felt true loss [in my racing], true depression,” he says, although as he does in the book Unser emphasises he has never been diagnosed with clinical depression, even in the worst year of his life in 2012 when he held that Colt handgun to his head. “Shelley had depression and would tell me about her head spinning, how she would get dizzy,” he says. “I didn’t get it. Well, in 1995 when we missed the show at Indy, flew back home and I went outside the next day I had that spinning where I was dizzy and almost fainted. I wasn’t supposed to be in Albuquerque. I was supposed to be at Indianapolis in the race, and it all came rushing back. Had it been with another race team it probably wouldn’t have hurt as much. There are responsibilities you take on when you work for The Captain. There’s automatic responsibilities and I felt I had let him down. I couldn’t escape that.”

“The crash hurt him more emotionally than it did physically”

In the chapter titled Dead Man Walking, Junior ruminates on the team never trying a softer rollbar all month as indicative of what went wrong. It’s hard to believe the tailspin Penske was pulled into. “It truly is,” says Al. “It was a God thing that had Penske missing the show. Roger himself waving off Emerson’s qualifying run because it wasn’t quick enough, but which would have made the cut. Then me jumping in the Lola from Rahal. The first time I drove it I was convinced I would run flat through Turn 1 and as soon as I turned the car almost spun right out, it was so loose. Woah, what the hell! Anything and everything went wrong. God’s in control of everything and He wasn’t done with me yet.”

The Beast: Unser Jr won his second Indy 500 driving for Penske with Ilmor’s special pushrod engine

Junior raced on for Penske, sadly with diminishing returns, until 1999 as his demons began to drag him down. As he says in the book, The Captain was always straight with him and he has no complaints that in the end a new deal was kept off the table. Today, Unser is full of praise for his old boss and the job he is doing running IndyCar and the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

“Roger is such a special person,” he says. “He’s going to make everything better. I actually can’t put into words what makes him special because he’s that unique. I used to think of him as a machine and machines don’t sleep. When I drove for Roger and actually had a relationship with him, I realised he’s a man. He works so hard at everything he does, but he is a man, he needs his sleep. Once I realised that it made him ever more special and unique. He’s blessed with the thoughts that God puts in his mind.”

In the early years of this century, Unser turned to the Indy Racing League to further his career, but by 2004 found himself driving a car without sponsor stickers. Arrests had occurred by now and the public was all too aware that this was one icon who had fallen far and hard. Attempts to stay on the straight and narrow, including a spell working for the IRL as a driver coach in 2008, tended to be shortlived. “The hits just kept on coming,” is how he puts it.

Roger Penske, left, and Al at the Detroit Grand Prix in 1999 – but Junior’s days at the team were numbered

The volatile marriage to Shelley ended in divorce in 1999, while his second wife Gina – who he once left stranded by the side of an interstate after a row at 3.30am – stuck it out for 12 years. How he behaved in his relationships with women makes for uncomfortable reading, as do his accounts of Shelley’s behaviour during their life together – especially as she is not here to have a right of reply. She died of cancer in 2018.

Unser says he made his peace with the mother of his four children, but you can’t help wondering how she would have felt about a book that lays bare so much that is personal. He pauses for a moment. “I would hope that she would say that she loves it,” – the chuckle is a little awkward this time – “I would hope that she would say that it’s truthful and that she approved.”

A reunion with Rick Galles took Al Jr back to Indy in 2000 for his first 500 since the Penske 1994 win. An overheating engine meant there was no fairy-tale

Today it seems Little Al is finally on the right track. As you’ll have probably gathered by now, his faith has become the central light of his life, he has a new partner Norma who “accepts me for who I am” – and he’s been sober since May 20, 2019. Unser has also worked his way back to motor sport, helping young racing drivers take their first steps with a Formula 4 team called Future Star Racing.

“Michael Andretti is such a success – and I’m such a failure!”

“Most of the kids that have real talent, the parents pay for their racing and it’s so expensive that they can’t make that next step,” he says. “I was born into the racing world and I was so blessed, to truly love it and enjoy it and have my dad and Uncle Bobby with the experience that they passed to me. Today, all I’m trying to do is pass that on, like Rick Mears, who helped me so much during the Penske days.”

Running on empty: no sponsor would touch Al Jr in 2004 when he ran a plain Dallara at Indy for Patrick Racing

It’s heartening to speak to Little Al from Albuquerque. But it’s heart-breaking too. He compares himself to his fellow second-generation racer Michael Andretti. “I look at him as a direct contemporary to me and he’s such a success – and I’m such a failure!” He says it with a big smile, but still… Michael never did win Indy as a driver. But Unser is full of praise for Mario’s boy. “He’s gone on to be an IndyCar owner, he’s looking at an F1 team now and I am so happy for him. He’s put in the work and he deserves the rewards.”

The final chapter of his book is titled Redemption. After all he’s been through, Unser surely has so much now he can give back. “I hope so,” he says. “That’s in God’s hands. I pray to Him all the time to help me with the words and wisdom to pass on. The glory goes to him, no matter what.” But it’s down to Little Al to keep on the straight and narrow. Keep your fingers crossed for him.

Al Unser Jr: A Checkered Past, is published by Octane Press.