Gordon Kirby

AJ Foyt racing's resurgence It's been coming for a couple of years under the leadership of AJ Foyt's youngest son Larry, and it came to fruition at Long Beach where…

The 1970s were a pivotal time in racing. cars became faster than they ever had been before as technology advanced at breakneck speeds, fuelled by the arrival of corporate sponsorship and intensifying manufacturer rivalries. Safety standards didn’t keep up resulting in a turbulent decade from which some of the best drivers the sport has ever seen simply never emerged.

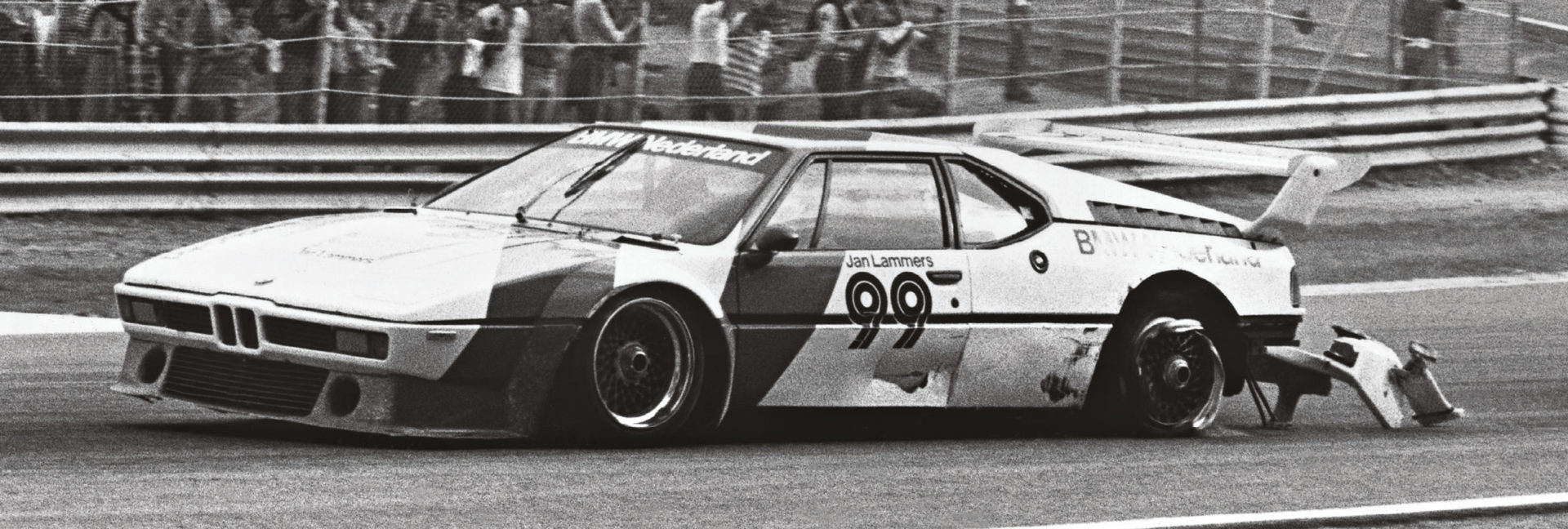

Jan Lammers, Hans-Joachim Stuck and Marc Surer all competed during this period, experiencing the highs and lows that also followed into the 1980s. Today these are still names that conjure images of ragged-edge racing and when we heard that they were reunited at the Norisring DTM round, Motor Sport went to meet them.

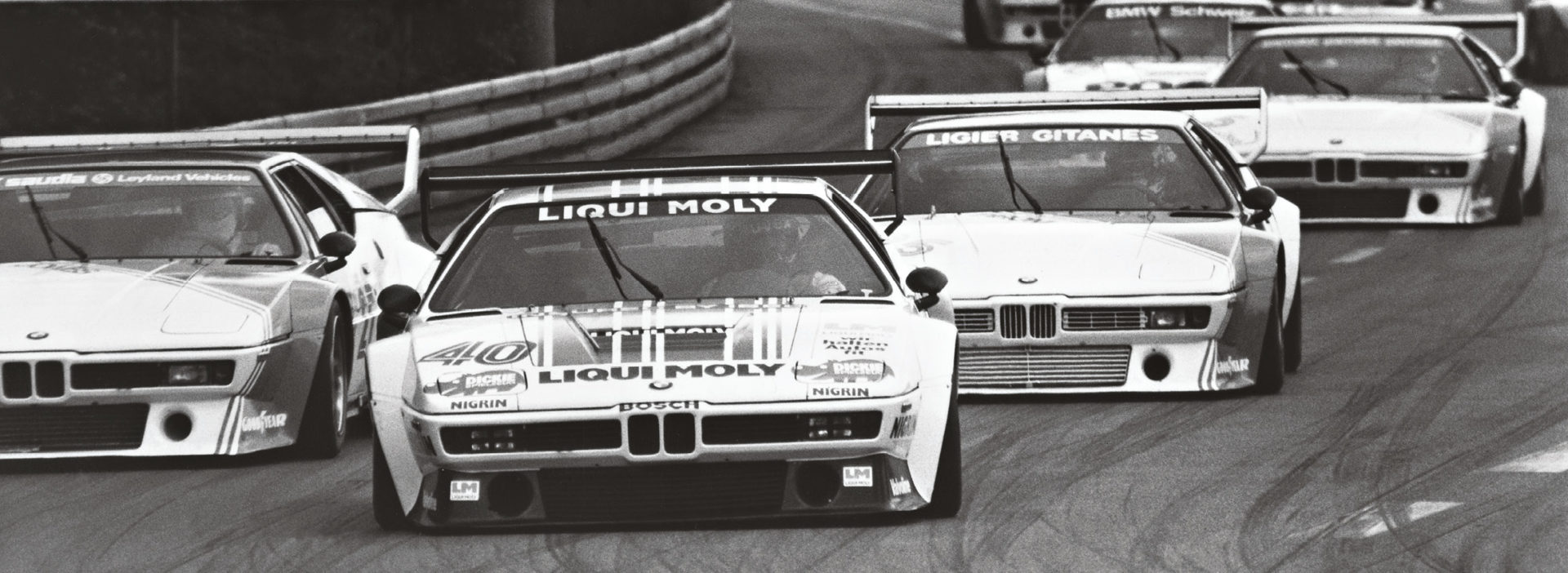

The reason for the reunion was a celebration of perhaps one of the best loved – but short lived – support series: BWM Procar. The races famously pitted F1 stars of the day against one another in BMW M1s, a concept born in a simpler time.

But to us the three drivers symbolise more than Procar. They epitomise an era that spanned sports cars and turbo-F1 – and they still bear the scars: Surer still carries a pronounced limp from his career ending accident. Between demo runs in their BMW M1s they talked cars, crashes and casualties.

“Motor racing has given me every-thing, my whole life. I’m still living a boy’s dream. When I was 12 I started working at a skid training school as a handyman, after school. And then from there, life revolved around racing.

Many of the drivers who have made it to F1 won in everything beforehand – F2, touring cars, F3… They are used to winning. Then they come to F1 and for years they don’t see a trophy anymore.

Artificially, you have to think of yourself as a winner. You always try to visualise: ‘I’m going to win today’. But when you drive an ATS or an Ensign or whatever, and you’re at the back, you need a lot of imagination!

I started in ’73. Cars were so much more physical in those days. By 1980 it was the days of the ground effect with the skirts, which brought extreme levels of downforce; it was like driving on a monorail. When it came to Saturday evening, physically you were absolutely finished. You were exhausted, completely drained. That’s why our heads started rolling around, because the muscles were drained.

And what people forget these days, in my opinion, is that it’s a fight. You know, like boxing, or soccer, which is a fight for the ball. This is a fight for the Tarmac – you’re fighting your competitors and the machine.

In our day it was a much more relaxed sport. Now there’s too much regulation; it’s over-moralised; it’s over-democratised.

Take the whole media thing, for example. In my day you would regulate it yourself and choose who you talked with. Now drivers are only allowed a few questions.

“I felt drunk, then passed out and only woke up on the straight”

Racing with Hans Stuck, I had great battles. He was always a tough guy; I was a tough guy. So we had lots of battles, but always fair and square, even if some drivers got into fights about on-track stuff. The funny thing is, it’s like in a relationship, the making up of a disagreement often is very nice. I think that’s what we had; we all did our stupid things, and whatever we did, it was mostly a mistake rather than bad intentions. You think it’s going to work and it doesn’t, and then you make up afterwards. That creates a bond. I think overtaking is an art. But blocking is an art also, and to defend in the correct way. Now even if you agree together you know the race director can interfere, so it’s a very different relationship.

Nobody gave a thought to penalties in our day. With the wings, the biggest fear we had was to touch another car. So we did our best not to touch because it damages your car, not because you get a penalty.

Procar was phenomenal. The idea was to bring the best touring car drivers in the world together with the best single-seater drivers. And it actually worked. Jumping back into the M1, immediately after the first lap, the feeling is there. It’s like muscle memory. And, you know, at some point, you feel you’re just as quick as you used to be.

I remember my first drive of the M1. We’d been testing with ATS and we had quite a lot of trouble. The car was handling badly and we had a rough day. The next morning, I jumped into the Procar for the first time at Donington. I drove a few laps, came in and said: ‘I thought the ATS was bad yesterday, but this is absolutely awful!’.

Then the team tell me, ‘You’re doing 12-one laps’ or something, so I said ‘So?’ and they explained ‘The fastest is 11-nine and you’re the one with old tyres!’

Physically, the M1 was not too bad. It’s just hot. The engine is very close to you. I once taped over the air vents, to try and gain a fraction more speed, and it set the fire extinguisher off. It wasn’t a powder system, it was one that sucks the oxygen away. So immediately, I felt like I was completely drunk, then passed out. I woke up on the straight and I’d dropped from first to fifth. I almost fought back to take the win, but I was about half-a-car length away.

I don’t think the future will be big tyres and big engines with loud sounds. It’s not of this time. Hopefully classic racing will always be there. But I don’t think the way sound appeals to us – to hear a 12-cylinder Ferrari or Jaguar engine – appeals to the newer generation. They can’t relate to it.”

“Racing gave me the best life but I paid for it; I had my accidents. And my moments of soul-searching. But I’m still here.

On a race weekend, you have ups and downs like people have in a whole year. So it’s an intense life. And in my era, before the rise of computers, it was often your word against the team’s, and that was tough. It was less electronic; no telemetry and all these things. So it was free racing because we were not made of glass. When you make a mistake now, you can see data; we came back from a lap and said these things happen and they couldn’t prove the opposite.

The F1 cars we raced had a tremendous amount of downforce, the same as today’s cars. Frank Dernie, from Williams, once told me we were pulling 4.5g. I remember taking Eau Rouge, in the Arrows; the chassis bent under the pressure and you could not steer anymore. The steering locked. So you had to turn before the dip. Teams started moving to carbon chassis, because the aluminium chassis was not working with the skirts.

At the same time, we had the madness of turbocharged engines. I hated them at the beginning. You cannot believe how bad the turbo-lag was! You’d brake, change down, turn in and go flat with the throttle, just to build up the turbo’s pressure again. And at the moment, the car starts to push wide, so you have to ease off, because otherwise you get understeer. It was a strange technique.

The only pleasure comes after you get out of the fourth gear. Finally, you could accelerate flat out, fifth and sixth, and you wanted to have a seventh and an eighth gear, because it started to go like hell. But up to fourth gear, with qualifying motors with 1400 horsepower, you were fighting wheelspin. It was like driving a dragster.

During my time in F1 there were a lot of lows, most due to reliability. At the Australian Grand Prix, [in 1985, driving a Brabham-BMW] I out-qualified Nelson Piquet, which was not easy, and in the race I was fighting for third with Niki Lauda and Alain Prost.

Then one tiny part failed, an injection pump. The team didn’t believe me. They said they fired up the car and it was running fine after they picked it up. They blamed it on driver error, because it stopped at the hairpin, saying that I went too low with the revs and stalled it. Then they went testing at Paul Ricard with the same engine and the drivers had to pull back into the pits twice with problems. They changed the engine. Only then did the team believe me. It hurt. Things like that hurt. I was not lucky in F1.

I remember a really frustrating day with the ATS, at Brands Hatch [in 1980], and the team was not happy with me and I was not happy with the car. Then I went to do qualifying in the Procar, and I got pole. When you sit in a neutral car and you beat all these F1 guys who are far away in front of you in F1, it is a moment of redemption.

That occasion was after my accident I had in F1 [where he broke his legs in the 1979 South African GP]. I hadn’t driven for four months, I did the pole lap straight out of the hospital. But in the race these guys overtook me because my legs were hurting.

After that first accident all I wanted was to prove to everybody I’m still there, I still can do it, so I did. After the second accident, I started to think differently [this was the serious accident at the 1986 ADAC Rallye Hessen in his Ford RS200, which severely injured him and killed his co-driver and friend Michel Wyder]. It had an influence.

“I handed the Porsche 956 over to Stefan Bellof at that Spa race”

I also did endurance racing. Those were scary times. The cars were so fast, with a lot of downforce and with aluminium chassis the protection was nothing.

I handed over the Porsche 956 to Stefan Bellof [before his fatal accident at the 1985 Spa 1000km]. And before that, there was Le Mans [1981]. I was just behind [Jean-Louis] Lafosse when he had his accident, and I nearly drove over his body, because he was hanging out of the remains of the car.

Le Mans for me was horrible because all the accidents that happened were due to technical problems. There were no driver errors. It was always a tyre letting go or bodywork falling off or something. You were just sitting there, waiting and hoping…”

“The three of us are very lucky that we are still here. I mean, in our days of F1, we had an average of a fatality every year. We had the track, maybe two metres of grass and then boom! So you had to have a lot of respect.

The driver was more the deciding factor in a race than now. I also drive modern race cars and it’s hard to say what is the better way. With a new car you can concentrate more on the sheer driving as the team monitors everything else. That’s why the distances are closer. With old cars, it’s more the driver that decides how to manage the car. I actually prefer the new race cars.

Jochen [Neerpasch, of BMW] is the best boss I ever had. I was educated by him; he got me under control. And the things he did in motor sport are just unique – fantastic.

When he revealed Procar, it was like the ultimate poker series. And I’d add, it still is the best one-make series ever. So I was excited, and there was no question I’d sign up. When you had these six top F1 guys, and you’d been driving in an ATS, which wasn’t a winning car, in Procar you could beat them.

In those days, there were weekends when you did sometimes two or three races. I remember I did Brands Hatch F1 on a Saturday, and then went racing at Diepholz in Germany on Sunday… the more the better.

I had the chance to drive for Project Four Racing, which was the Ron Dennis team, and you know how immaculate he was, or is. When the mechanics were driving the car from the truck to somewhere they had to put on shoe covers to keep it clean!

But in fact, between the Cassani car and the Ron Dennis car there was no difference. Maybe Ron’s was a bit cleaner, but the performance was the same.

The racing was close, especially at tracks like Monaco, where it’s hard to overtake. Because we drove this car more often than the others, we were better connected to it. And when you out-braked somebody going down from Casino, it was like heaven.

It was encouraging you to push harder, you know, because you beat guys like Clay Regazzoni or Carlos Reutemann. But it was fair racing. There weren’t any tricks; we didn’t hit each other on purpose. It was fun.

The good thing was at the end of the year when had to talk about next year’s contract, you’d say, ‘Hey, I won Procar, I beat these guys, a bit more money for next year would be nice’ and it’s the best argument.

There is a good story about us drivers during the development of the M1. To get the road certification, BMW needed to do 100,000km of road driving in a short time. So, under pressure of deadlines for the project, there was Marc Surer, Ronnie Peterson, me and a few others. We had four weeks and we did four tours each morning, where our convoy would cover 250 kilometres through to Bavaria, then we’d come back, refuel the car then hand it over for the next drivers and their stints.

After every weekend we had to change the route because we were running over the farmers’ hens and not obeying any speed limits. It was such a fun time! We knew the car like our baby and we all agreed it would make a cool race car. The moment Jochen [Neerpasch] said BMW take it racing we were on fire because the car was so nice to drive.

I’m lucky. I don’t need to motivate myself. I get so much joy out of driving. Is that the same for today’s F1 drivers? I was at the last three GPs and an employee who runs the paddock told me a story. I won’t name names: two drivers came by in the morning complaining that they have to walk 30 metres through the public to the paddock entrance. The drivers asked, ‘Can we make a special deal? Can they drop us off somewhere else so we can enter by the back door? We hate going through the public.’

“I’m an ambassador for VW, but I still say whatever I think”

Can you believe this? This sport can’t be in their hearts. They do it because of money.

Now you have huge companies like Mercedes, Ferrari, Renault in F1 and they expect drivers to be ambassadors, which is right on one hand, but it doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t say what do you think.

I work for the VW Group as a motor sport representative but I always say I say what I think. Even if sometimes they don’t like it.”