Back-to-back Monaco and Pau Street spectaculars

For lovers of street racing, May offers a feast, with two spectacular Gallic meetings. A superb array of many of the world's leading historic cars will be in action during…

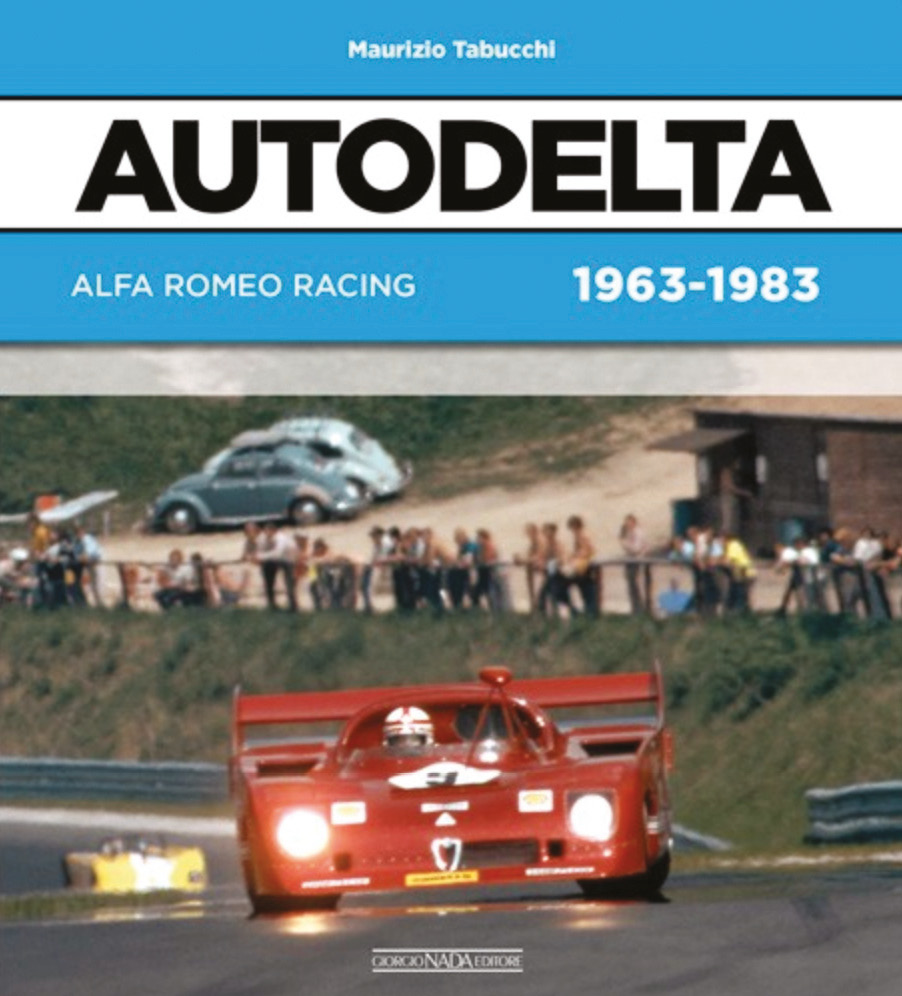

Maurizio Tabucchi, published by Giorgio Nada, £45,

ISBN 978-88-7911-713-5

Over the years Alfa Romeo has often relied on an outside outfit to run its racing programmes, from Scuderia Ferrari onwards. But in the lifetime of most reading this magazine it’s been the word Autodelta that has accompanied the (usually) scarlet cars onto the grid, through the 1960s and into the ’80s. This hefty work provides the story of this quasi-independent outfit which improved, developed and built the marque’s racing entries from disputatious beginnings to what the final chapter heading calls “a humiliating ending”.

Turning first to that humiliation, things grind to an unsatisfactory halt in 1985 on the F1 grid, with Benetton green swamping rosso corsa on Eddie Cheever and Riccardo Patrese’s B185Ts, in the same way that the name Euroracing swamped the Autodelta badge. Aggravated by what he viewed as incompetent management, the revered Carlo Chiti, designer and engineer for Alfa, Ferrari, ATS and Autodelta since 1953, walks out, helped on his way by an institutional belief that ‘the old man’ was failing his task.

Tabucchi seems clear that the mistake was involving previously successful F3 team Euroracing, stating: “The indomitable Chiti had his revenge in witnessing the demise of Alfa-Euroracing”. He goes on to berate the company president: “who was conditioned by a thousand jealousies, a thousand pieces of poor advice”, and then quotes Chiti’s bitter words about individuals wanting to destroy Autodelta in the run up to Fiat ownership. Impartial this is not. Which may not be good history, but it lends pep to the rather flat text, though that could be due to either the author or translator.

Despite a brief spark of the Alfa Corse name in 1992, Tabucchi sees all this as the end of Alfa Romeo racing at the top level. Events have slightly overtaken this wrap-up with the logo currently re-applied to Sauber, but then Autodelta was never really about grand prix racing. Its great days involved making production cars victorious in GT events and building some of the most glorious sports-prototypes ever.

That’s where it began, in 1963 when the Alfa chairman decided the firm needed an outside organisation to build and prepare 100 prototype TZ coupés – and swallow the blame if they didn’t win. The hugely knowledgeable Tabucchi gets here after a rapid run-through of Alfa’s competition origins and the Scuderia Ferrari years, and then being pushed off the top table by Ferrari and Lancia. But if grand prix racing was beyond it in its 1950s period of radical restructuring, Alfa was well set with its new lightweight twin-cam Giulietta motor to make its mark in saloon and GT racing. Remarkably, that engine – in multiple guises – would carry it through to the 1990s.

But it deserved a lightweight home, hence the TZ with its tubular chassis and Zagato body – and a GT homologation requirement for 100 of them, too much for the firm to handle. That’s where the new outfit came in. It built and raced the TZ, the stunning TZ2, the lightweight GTA and the Cortina-rivalling Ti saloon. (Tabucchi has sarcastic things to say about Lotus’s “inappropriate” Cortina mods.) Through the Sixties these small Alfas brought glory to the marque and led on to the 33 sports-prototypes which would eventually bring Alfa two World Sportscar Championships.

I learn a couple of things here: the 33 was initially created by the Portello works, not Autodelta, and it was handed over to AD with no engine. It was Chiti’s inspiration to utilise a smaller variant of the ATS V8 that he had almost ready to go.

It’s lucky that the book is laid out with sidebars – on designers and regular Alfa pilots such as Lucien Bianchi and Bruno Giacomelli and a first-hand account of driving a TZ2 – as this and many excellent photographs leaven the somewhat relentless march of the text. But the author’s catty asides liven it up: in the 1969 Targa Florio when Nanni Galli’s 33 goes off avoiding Vic Elford’s Porsche 908 Tabucchi claims: “Alfa suffered directly from the Stuttgart firm’s arrogance”. Things seen in the rear-view mirror are often distorted… In any case, Elford would later race Alfa’s 33TT3.

“Ecclestone accused Alfa of ‘wasting time and money on a car that was five seconds slower’ ”

Woven round the arrival of the 3-litre and flat-12 33s which would finally earn their crowns is more infighting: Franco Scaglione, the coachbuilder who shaped the gorgeous 33 Stradale, fell out with Chiti over it. This time Tabucchi gives both men their say.

A return to F1 with Brabham was another roller-coaster: as well as Alfetta GT rally cars and the Alfasud Trophy, Chiti was also developing his own Alfa-Alfa for the marque’s return as a constructor, while trying to comply with Gordon Murray’s demands to ditch the flat-12 engine for a V. It led to more scathing words, this time from Bernie Ecclestone about “wasting time and money constructing his car which proved 5sec slower than ours”.

Bernie was right. Thereafter, despite early promise with the V12 and two podiums with the 1983 turbo V8, the Quadrifoglio drifted down the F1 grid to that humiliating end. It’s a rich history, full of drama, triumph and disaster, and the book is generously illustrated with many unseen pictures – I loved the shot of a Disco Volante being threaded through the narrow doors of a DC3, and one of seven blue-overall testers watching a GTA on the Balocco test track, and I’ve not before seen the open-topped TZ prototype. So there’s much to enjoy here, often first-hand; it’s just a shame I have to say it’s more ‘worthy’ than thrilling.