Laughing as he recalls the image, Damon is refreshingly candid about his attitude to the sport that surrounded him throughout his childhood until his father’s untimely death in 1975. “That sort of grand prix put me off motor racing for a long time,” he admits, and when you look closely at Graham Hill’s distinguished career, and talk at length to those who knew him best, clues begin to emerge as to the reasons for the young Damon’s disinterest. His mother, Bette, casts first light on the influences on her young family in the 1960s.

“Don’t forget that when Graham was racing they did so much more competing than a modern F1 driver,” she reasons. “Every weekend they were racing some single-seater, sports car or saloon. With the stakes so large and time precious, you had to try and remain a human being. When Graham got back with his family he found it very easy to relax.” And, understandably, forget about racing for a few days. So his children saw motor racing much as any other young child views his or her parent’s profession – a job to be done and little more.

If racing was to be Hill jr’s future, it needed a spark and that came, his mother recalls, when aged 11 he had a taste of two-wheeled motoring. “Graham and I always thought Damon was too intelligent to be an F1 driver,” smiles Bette, “But when Graham put him on a Honda trial bike the penny dropped. From that minute it was all motorbikes.”

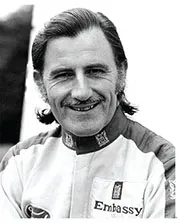

Graham led Lotus in similar tragic circumstances to Damon at Williams

Grand Prix Photo

Damon’s accomplishments as a rider are well documented, as are his mother’s concerns about her son’s safety. Not wanting him to continue to the point where his motorcycle career would lead to yet faster machines, she arranged for him to try four wheels. “As soon as he did it,” she recalls, “he told me he wished he’d started five years earlier.”

A couple of seasons of Formula Ford gave Damon a grounding in racing and while some point to early failures as an indication of a scarcely overwhelming talent, it is an opinion that holds less weight with those against whom he raced. As a Formula Three racer he was fast enough to clinch a prize drive alongside Martin Donnelly the prize being backing from Cellnet, a sponsor of Damon’s to this day, and an early source of much needed income. Contracts like that were barely heard of in Britain in the mid-1980s and Damon’s securing of that seat reveals traits that helped his father 30 years earlier and would help him again ten years further on in his own career. “Cellnet wanted to know they had the best two drivers possible,” recalls Donnelly today, “and they sent us off to have our fitness assessed by Jonathan Palmer. It was interesting to see how Damon acted during those tests. We ran on treadmills until we literally fell off and then we were sent training with commandos. We were really put through it. At the end the report said while I was marginally fitter, Damon was more determined. If I did 51 bench presses, he had to do 52. And that’s Damon through his career: determination allied to refusing to lie down and play dead. In that way he’s a bit like Nigel Mansell.”

And rather more than a bit like Graham Hill. Ask Bette what one word she thinks best describes her late husband and son in respect to their careers and the answer comes instantly: “Tough”.