Their test figures for it included an average maximum of 176.47mph and acceleration from 0-60mph in 6.8sec and 0-100mph in 13.6sec. Doesn’t sound too stellar today, does it? But this was more than a half century ago… More significantly, it punched itself from 50-70mph in 2.5secs, 60-80mph in 3.1, and 80-100mph in 4.8. It really was an absolute rocket ship, and in period absolutely the world’s fastest road car.

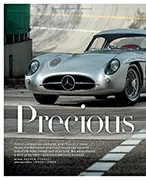

So digest that stature – backed by the unbeatable racing provenance of the 1955-season 300 SLR roadsters (winning the Mille Miglia, the EifelRennen, the Swedish Sports Car Grand Prix, RAC TT and Targa Florio, and being withdrawn post-accident at Le Mans when running first and second) and what do you have? As one leading classic car dealer gasped – “God Almighty! If it ever became available, I’d be confident of serious interest from several players at 50-60 million dollars…”. In other words, ‘The Uhlenhaut Coupe’ is a candidate for being the world’s most valuable motor car.

And I found myself let loose in it. But I’m happy to report that ‘Red’ and I both survived, unscathed. I suspect my companion in the car, Gert Straub, was not so confident. He has cared for the Museum cars for years. He’s a fourth-generation Daimler employee; his father Horst rode with ‘Taffy’ von Trips in a works 3005L during the 1956 Mille Miglia. It was horribly wet, and Trips drove like a man on a mission before crashing heavily. He and Horst Straub escaped serious injury, but the car was destroyed. Did his father express an opinion on Trips’s driving? “Ja. He told me Trips woss total nuts!”.

Gert Straub and Doug Nye at the helm

Now Gert fussed around ‘Red’ like a mother hen, telling me he had been concerned by “a noise in the back axle”. I got the message. “It’s OK, Gert – I’ll treat her like cut glass”. He nodded, clearly unconvinced. He removed the hatch in the driver’s door sill, connected the battery within, then released the steering wheel lock and slid the four-spoked wood-rim from its splines. Sliding down into the driver’s seat he reached across to the magneto switches, click-click, further across for the ignition key – on – push in for the electric fuel pump. An insistent whine from the tank-filled boot primed the Bosch fuel injection – then Gert pressed the starter button on the left of the dash panel. Down below that long, shapely bonnet the 3-litre straight-eight engine began to clash over, chassis shuddering. I pictured those eight pistons shuttling virtually from side-to-side in their cylinders since they are canted at just 33 degrees from the horizontal to minimise centre-of-gravity height.

Cough — ker-BLAAAAAMMMM! Now when I described years ago what the V16 BRM was like to drive, one reader criticised my trying to spell “infantile mouth noises”. Well, please accept my apologies, but I’m at it again. Incredible, cacophonous, car-splitting noise is what the 300 SLR is all about. Conventional language just doesn’t express it. When he tested the sister Coupe in 1956, Gordon Wilkins wrote: “…as soon as one touches the starter button there is a shattering noise from the engine which momentarily numbs the senses. It is compounded by the whine of the gears, the clatter of the desmodromic valve gear and the injection pump, and a variety of grinding noises from the vicinity of the clutch housing…”.

The ensemble settles down into a thunderous warm-up at 3000rpm — Gert occasionally whooping it to 4000. Once warmed through, he switches it off. Silence reigns. We roll the car around the end of the shops and line it up beside the main road, ready to join the Retro pack as they career by. A small admiring crowd gathers. One asks, in English “Is this…” — a reverential intake of breath — “…the Uhlenhaut Coupe?”