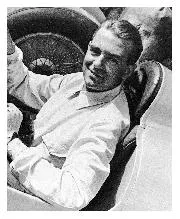

Like every driver of real stamp down the ages, Rosemeyer was outstanding from the moment he began. Briefly he raced motorcycles with success, but grand prix racing was his aim, and over the winter of 1934-35 Auto Union gave him a test, following it up with a contract of sorts.

Invariably Auto Union played second lead to Mercedes-Benz, for the unwieldy rear-engined cars were very difficult to drive, and the best drivers were usually on the Mercedes payroll, led by Rudolf Caracciola. In 1935 Auto Union’s leading men were the consistent Hans Stuck and Achille Varzi, the wayward genius whose best years were tragically squandered to morphine addiction.

Auto Union had need of a major star, and Rosemeyer believed he was the man. But when the entries were posted for the first German race of the season, at the Avus, he found he was not down to drive.

Two weeks to go before the Avus. Will Rosemeyer get a drive?’ Auto Union’s team manager began finding notes scribbled on his calendar, and this continued until eventually he relented. Rosemeyer did drive at the Berlin track, and within weeks became the team’s mainstay. He mastered an Auto Union as no one else, even Tazio Nuvolari, ever did, perhaps because he had nothing to unlearn. He never raced a front-engined car before driving the tail-heavy machines; indeed his first race in any car was that event at the Avus.

With wife Elly Beinhorn

Audi

Once in a generation, this sport throws up a man whose talent and personality meld inexplicably to produce a kind of magic, which puts him on a plateau, alone. Villeneuve had it, without a doubt, as did Ayrton Senna and so did Rosemeyer.

That first season, 1935, ended with a victory, in Czechoslovakia, and the following year was one triumph after another, even though his battle with Mercedes was invariably a lone one, for Auto Union had no other driver remotely of his class. Rosemeyer had an absolute inability to give up, charging at all times, leading or not. In 1936 he won at Berne, Pescara, Monza and the Nürburgring, and thus became European Champion in only his second year of racing cars. The concept of the Auto Union ensured that it was an oversteering car, which tended to snap sideways very suddenly. It was this characteristic which Rosemeyer exploited to such advantage. Where lesser men were intimidated, he was at ease. Yet his driving was only part of the story. At a time when Germany was preparing itself for war, Rosemeyer’s personality pleased his countrymen, a refreshing contrast to the quiet Caracciola and the haughty Manfred von Brauchitsch.