Herbie Blash — The Motor Sport Interview

He’s never been one to generate headlines, though Herbie Blash has worked with many who have – not least Chapman, Rindt, Ecclestone, Lauda and Piquet. Time, then, to usher him into the spotlight

Given the fanfare that accompanied his departure as Formula 1’s deputy race director in 2016, you might imagine that Herbie Blash – gofer at Rob Walker Racing, number two mechanic to Jochen Rindt at Lotus and long-time Brabham team manager, among other things – would have spent the past few years with his feet up, looking back on a life he acknowledges to have been “privileged”.

He was barely out of his teens when he began travelling around the world with the sport he loves, but he hasn’t exactly applied the brakes since stepping away. He has always had a habit of wearing different hats, has worked with Yamaha for some 30 years and maintains a role with the Japanese firm as a consultant to its World Superbike team. He is as busy as ever at 72 and it took several months to prise him away from endless conference calls as he and his counterparts fought to shape a workable WSBK calendar in a Covid world.

We meet in West Sussex to chat about his life, some elements of which might surprise. For instance, Chichester University awarded him an honorary business doctorate for services to motor racing. “Not sure why,” he says. “I’ve never mentioned that to anybody.”

Motor Sport: You were born Michael Blash, yet everybody in the sport knows you as ‘Herbie’. Why is that?

Herbie Blash: “When I started working for Rob Walker, my first job as an apprentice on the road car side, Tony Cleverly was chief mechanic for his racing team and for some reason nicknamed me Herbie. I thought I had a chance to go back to being Michael when I joined Team Lotus, but I arrived in Norfolk and went with the lads to the pub for a game of darts. When they put me up on the scoreboard as Herbert, I pointed out that my name was Michael and that was the worst thing I could have done. After that I was Herbie and never did shake it off. Away from racing, everybody calls me Michael. My wife’s mum always thought she’d been dating two people.”

How did you first tune in to motor racing?

HB: “Once each term at junior school we would have an afternoon of films, including the old Shell motor sport documentaries, which hooked me. I was also following motocross – or scrambling, as it was called – on TV. From the age of 12 I was driving tractors through the fields on a smallholding, where I also had use of a Ford Popular and a Triton motorcycle with no rear suspension. I used that for my own version of motocross, so I already had an interest in mechanical things.”

At 16 you began working at Rob Walker’s Pippbrook Garage in Dorking, where his racing team also happened to be based.

HB: “I was hired for a role in the main garage, though there was a special area set aside for the sportier cars, such as Lotus Cortinas, and I was lucky to have an opportunity to work on those. And then I was asked to wash the race truck. After that, whenever I had any spare time, I’d always try to get to the racing side to polish the cars or practise a spot of aluminium welding – anything that would help me learn.

“At that stage I’d never attended a race, but I went with Rob’s team to the 1965 Sunday Mirror Trophy at Goodwood. We ran Brabhams for Jo Siffert and Jo Bonnier and I was the gofer. The thing I remember most is that Jim Clark won everything – the F1 feature in a Lotus 25, the British Saloon Car Championship race in a Cortina, the Lavant Cup in a Lotus 30. I know it’s impossible to draw comparisons when discussing drivers from different eras, but I do think he was probably the best there has ever been – and certainly the best I ever saw.”

Now in his seventies, Herbie is still involved with the nuts and bolts of motor racing

Richard Davies

When did you make a full-time switch to working on racing cars?

HB: “Not until I joined Team Lotus at the end of 1968 – an indirect consequence of a horrible workshop fire at Pippbrook. Jo Siffert had crashed Rob’s Lotus 49 during the Race of Champions at Brands Hatch and it was being stripped down prior to the monocoque being sent to Lotus for repairs. It could have gone back as it was, but one of the mechanics decided to remove a couple of bits that were pop-riveted to the chassis – and he was using an electric drill. In those days we washed everything off with petrol and there were trays of the stuff lying around. A spark from the drill landed in one and the whole place just exploded. Tony Cleverly and I were stuck in the corner, but there was a window and we were able to get through that. There was nothing we could do. We just had to stand and watch Rob’s racing history go up in smoke. The building burned for nearly two days.

“Colin went ballistic, stormed out and dragged me with him”

“In some ways, it became a positive for me. I did a lot of van driving for the team and after the fire often visited Lotus to collect parts, which meant I got to know the people there. They offered me a full-time job at the year’s end.”

“A spark from the drill landed in a tray. The place just exploded“

But Lotus didn’t hire you as a van driver…

HB: “No! I was straight onto the race team as number two mechanic on Jochen Rindt’s car for 1969, working alongside Eddie Dennis. We did two seasons together and I was also assigned to Graham Hill at Monaco in ’69, after Jochen had been injured in Spain. Socially Graham was fantastic – he’d always buy the lads a beer – but in work mode he was very demanding. We used to have spacers on the steering column and he decided he wanted the wheel one quarter of an inch closer to him. Colin Chapman would always produce a job list, 1-20, and Graham would do likewise. I got the impression that Graham was just filling up the numbers, so on this occasion I ticked the sheet to say I’d moved the wheel – though I hadn’t actually touched it. The following day he decided it was now too close, so he wanted it adjusting again!”

In the thick of it in 2017, deep in conversation at Donington Park in the pitlane with Yamaha

Death wasn’t unusual in the sport – and you lost Jochen, the first driver with whom you’d worked on a full-time basis. Did you regard such things as an occupational inevitability?

HB: “Yes. You have to remember that the sport had been through a terrible time over the previous couple of seasons. Many teams were staying at the same hotel for the 1969 German GP and I remember seeing Gerhard Mitter in the breakfast room. We were chatting about a trip to the bowling alley that evening, but he was no longer with us by then. I think that was the first time it really had an impact on me.

“Most of the team left Italy quite soon after Jochen’s fatal accident, but I was left behind with Bernie Ecclestone [then Rindt’s manager] to sort out various bits and pieces. I had to take Jochen’s car back to Switzerland. His wife Nina was waiting on the balcony when I arrived, and Piers Courage’s widow Sally was already there, trying to comfort her. Jochen’s daughter Natasha was about two at the time and came to the top of the stairs, shouting, ‘Papa, Papa.’ That’s something I’ll never forget.

“I did consider quitting the sport at that point. I travelled back to the UK with Piers’ brother Charles and sat there thinking, ‘Nah, this isn’t for me.’ It didn’t take long for me to change my mind, though. I’d been thinking about managing my own F2 team and Lotus was going to build a car for me to run in 1971. That didn’t happen, however, because the money never arrived. One of the Lotus guys, Mike Young, had left to work for Frank Williams and he asked if I’d like to join him.”

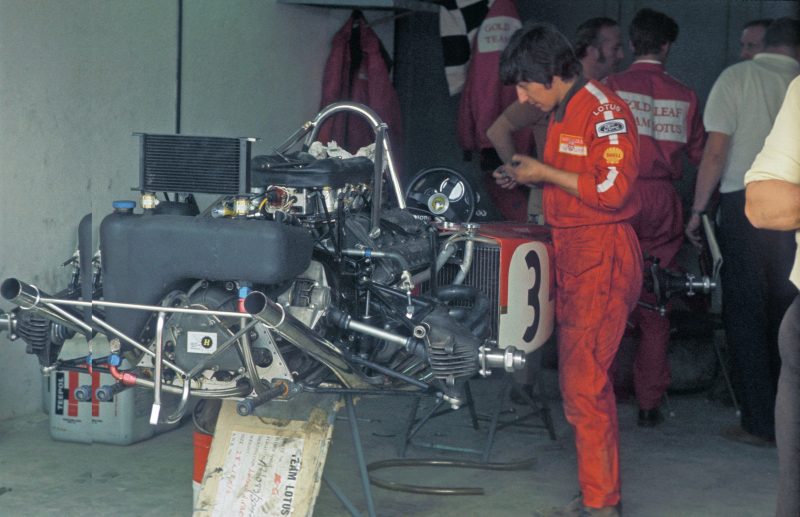

Jochen Rindt’s Lotus keeps Herbie busy at the 1970 Spanish Grand Prix, although the car would retire on lap nine

The internet claims you left Lotus after a massive row with Colin Chapman, which means it probably isn’t true…

HB: “It isn’t. There was a story going around that I was trying to get everyone at Lotus to go on strike, but I don’t know where that came from because it was nonsense. I did stand up for some of the guys against Colin, but he and I had few run-ins. There was one at Barcelona in 1969, my first year with the team. Colin had realised that the bigger the wing, the faster you went. After the first day of practice we went back to our base, a garage in Barcelona, and unloaded the cars. My job was to extend the front wing flaps, and in the process I used up one full big sheet of aluminium. Colin arrived at about 4am with an idea for extending the rear wing, which meant they’d need the sheet of aluminium I’d just cut in half. He went ballistic, stormed out and dragged me with him. He told the guys, ‘That’s it, we’re not racing – load up. We’re going home…’ He took me to an all-night café, told me about a carpenter who had cut too much from a door and how you must be careful not to go too far. When we went back to the garage, he wanted to know why everybody was standing around rather than preparing cars for the next day!

“On another occasion, I filled the saddle tank on a Lotus 49 while Colin and designer Maurice Philippe were standing nearby. I was doing this after an all-nighter and had forgotten to replace the drain plug, so the oil was running straight through onto Colin’s beautiful suede shoes. He wasn’t impressed.”

Although you accepted that initial offer to join Williams, you didn’t stay very long. Why?

HB: “Because at that stage Bernie was set to buy Brabham and asked whether I’d like to give him a hand. I’d first met him in 1969 – I think at the Race of Champions at Brands Hatch, when he was with Twiggy and her manager Justin de Villeneuve, which impressed me. I knew nothing of his background, only that he was Jochen’s manager. I liked him because at Monaco in ’69, when Colin and Graham Hill were compiling their job lists, Bernie actually dragged Colin away before he’d completed what he was doing – his way of looking after the mechanics, making sure we didn’t have too much to do. And joining Brabham would also give me a chance to run my own F2 team.

“My stint with Brabham didn’t last long, though. On my first day, we were looking at doing some mods to a BT33 and I drilled into the sideskin – as we would have done at Lotus. Ron Tauranac came in, screaming that I’d ruined his monocoque. We just didn’t get on, so I decided to leave and went back to Frank Williams to look after Henri Pescarolo in F1 and F2… but it wasn’t long before Ron moved on, at which point I returned immediately.

“The idea was that I would put together a works F2 team for 1973, with a smart articulated truck and three cars – for John Watson, Wilson Fittipaldi and Andrea de Adamich. John broke his leg at Brands Hatch in March, Andrea lost his engine deal and I ended up with a car for Wilson plus a van and a trailer. That season I was doing F1 and F2 where my chief mechanic was Gary Anderson, who of course went on to be very successful, and also sometimes kept an eye on our F3 programme.”

How was life at Brabham at the dawn of the Ecclestone era?

HB: “When the team was based in New Haw, after he’d first taken over, he would visit once a week. This Rolls-Royce would turn up and I’d run through the factory whispering, ‘He’s here,’ so that everyone could put away their sandwiches and make sure they were flat out by the time he walked through the door. If he wasn’t happy with something he would shout and scream; I don’t know whether that was designed to put fear into people, but it did.

“We moved to Chessington, and it became procedure that Bernie would walk into the workshop and you’d hear, ‘Heeeeerbbie!’ – I’d have to take the brunt for everything, whenever somebody had failed to turn off the toilet light or whatever. It was always my fault!

“In 1978 I hired Charlie Whiting from Hesketh as chief mechanic. We worked together from that moment on. We used to be known as ‘the odd couple’ and it was a long marriage. The biggest difference between us was that he preferred Chablis while I’d order Sauvignon Blanc.”

You remained with Brabham until Bernie sold it in 1988 and worked with some exceptionally fine drivers. Carlos Reutemann…

HB: “He was very emotional and could be led by other drivers – especially Jackie Stewart! Jackie would say to him, ‘I wouldn’t use those tyres.’ They’d have been fine, of course, but in Carlos’ mind they now weren’t. He could be distant. He was once arrested for walking out of Harrods while wearing a golf glove for which he hadn’t paid. He’d have tried the golf glove before being distracted by something else and forgot all about it – he certainly had no intention to steal it. On his day he was absolutely untouchable, but he just wasn’t sufficiently consistent. He should have beaten us to the 1981 world title when he was racing for Williams, but he was psyched out before we reached the final race in Las Vegas.”

Brabham’s Gordon Murray, Hans- Joachim Stuck and Herbie Blash at Zandvoort, 1977

Carlos Pace?

HB: “Given time he could have been a world champion – a brilliant talent, taken too soon [Pace was killed in a light aircraft accident in 1977]. He wasn’t a hard worker but his natural ability could have taken him to the top. Now you’d need the dedicated work ethic on top of that, but back then cars were very simple.”

Is John Watson unfairly underrated?

HB: “Very much so. He won five grands prix, but imagine how many more he might have won if our car hadn’t failed when he was leading. Could he have been world champion? Yes, in the right circumstances. If you mention his name today many won’t know anything about him, but that’s because he didn’t make much of a fuss. Some others – James Hunt, for instance – promoted themselves naturally, whether or not that was their intention…”

Andreas Nikolaus Lauda?

HB: “He was fabulous to work with. I knew him well before he joined Brabham, from his F2 days. I was with him in a small night club in Austria in 1973 when he told me he’d signed his Ferrari contract for the following season. He was sitting in the corner with his drink, which in this instance was a bottle of whisky. Perceptions are different when you look back at James Hunt and Niki Lauda, but Niki used to drink and smoke – and had a similar interest in chasing women – but he was more discreet.

“I remember tyre testing with him. Every couple of hours we’d go back to the control tyre to establish a benchmark time as the track evolved throughout the day – and we’d always finish on the control tyre, too. One day he was desperate to leave and I was insisting that we do one more run on control rubber. He thought it was pointless and told me exactly what time the tyre would do, but I sent him out anyway. I never used to show lap time boards during tyre tests because I didn’t want drivers drawing conclusions until we’d finished, but he went back out… and was correct to within one hundredth of a second. After that, whatever Niki said was fine by me.

“When he joined us and tested for the first time at Interlagos, he set out and never came back. It took a while to find him, because he was buried beneath a pile of catch-fencing where he had been sitting, trapped. Somebody had accidentally drilled through a rear brake pipe, which didn’t help. He emerged with no more than a cut hand, but at no stage did he shout or scream – it was just something that had happened, a fact, and that was Niki.”

Nelson Piquet is rarely cited as one of the greats, despite everything he achieved…

HB: “I know, but you don’t win three world championships unless you are very special – and let’s remember that he was up against Niki in his early days, then Senna, Prost and Mansell. I remember Niki saying, ‘Jesus, this guy’s a bit too quick.’ In the early days his work ethic was second to none. He’d be in the factory, in the drawing office, talking to the mechanics, coming up with ideas. I first got to know him when he was racing in F3. To get extra straight-line speed in a race at Paul Ricard, he kept his belts slightly loose so that he could slide down a bit in the cockpit and gain an aero advantage along the Mistral Straight. From a safety perspective it was bloody crazy, but he was always looking for tiny advantages. He and Gordon Murray were a formidable team.

“I’d like to add, by the way, that people don’t give Martin Brundle due credit. He was very naturally talented – and at the end of each race he would always do a full report in really good, clear detail, making suggestions about what we could do to rectify problems. He was quick, a hard worker and many folk don’t realise just how good he was.”

There was a driver named Blash who didn’t quite match that description…

HB: “Yes… that was at Zolder in 1975. We had just signed with Martini and they wanted to mount a camera on the car when we got to Monaco, to produce a marketing film. We were doing a private test and the cameramen turned up for a trial run during the lunch break. I asked Carlos Reutemann to jump in, but he wasn’t interested because he wanted to eat so I decided to drive. It then started to rain heavily – and I was on slicks. I thought I was fully under control until the second lap, when I suddenly found myself flying through the catch-fencing. I walked back to the paddock and told Bernie I’d possibly damaged the rear wing endplates, but when it came back the rear end was hanging off, the front-left corner was missing and so on. I’m not sure Bernie ever saw the funny side. From then until the day he sold Brabham, every time I looked at my pay cheque I felt I was still paying for the damage.”

Herbie had a long association with Bernie Ecclestone (left), seen here with Gordon Murray in their Brabham days at the 1983 British Grand Prix. The team’s drivers that season were Riccardo Patrese and Nelson Piquet – who would be crowned world champion in October

Care to share any of the little tricks the team had up its sleeve?

HB: “How far can I go? When we were testing in Brazil, we’d damaged a chassis and didn’t have the spare parts. The car for the race had turned up, but was locked in customs. We managed to bypass all the airport security, break in and swap the cars at 3am, which meant we could continue testing. But the press got hold of the story and journalists were swarming all over Bernie, who had just arrived and started screaming at me through my car window. I gave it a bootful of revs and dropped the clutch, but the handbrake was still on…

“We ran a lightweight car one year in Monte Carlo but put the heavier body panels back on before it was checked. And then there were the sidepod water tanks, which we’d drain before it went to the grid and then top up afterwards to restore the weight. In those days, even in parc fermé you were allowed to top up the fluids, which was a ridiculous rule – but we weren’t the only team doing that. Everybody was at it.

“Remember that Brabham also came up with things like tyre heaters, refuelling stops, air jacks and carbon brakes – so there was lots of innovation in between trying to bend the rules.”

Brabham scored its final grand prix victory at Paul Ricard in 1985. Could you feel the magic ebbing away?

HB: “I think that started to happen when Nelson left for Williams at the end of ’85. The following season’s BT55 wasn’t competitive. We were using the BMW engine, and the way it lay down in the chassis meant the scavenge system didn’t work properly – and Gordon departed soon after that. You also have to remember that by this time Bernie was pretty much running F1 – and the bigger his role got, the less interest he had in Brabham.”

For much of the 1979 season, Brabham was using Alfa Romeo power. Blash inspects at the German GP

Grand Prix Photo

When Brabham withdrew temporarily from grand prix racing in 1988, you ended up running F1’s in-house TV department. How were you qualified for that?

HB: “I wasn’t, but Bernie more or less told me I’d be doing it. I remember turning up at the first race in Brazil, when the BBC and RAI came up to me and asked if they could have the first unilateral [satellite time]. I didn’t know what that was. I phoned the European Broadcasting Union and they were surprised that I hadn’t booked anything… I was thrown in at the deep end.

“Bernie sold Brabham to Walter Brun during the course of that year – and he swiftly moved it on to Swiss financier Joachim Lüthi, who invited me to go back to running the team. I was happy to do that, but the money ran out very quickly and he ended up in prison. That was one of the hardest periods of my career because I had to try to maintain the team – with a little bit of help from Bernie. We managed to get to the end of the season, which is when Middlebridge stepped in to take over.

“The riders are some of the bravest sportsmen I’ve met”

“Late in 1990, I was rooting around in the office and found a letter with a Yamaha logo. They had written asking whether we would be interested in using their engine and it had been sitting there a few weeks, because at that stage who wanted to be with Yamaha? But we were in survival mode, so the following morning I called Japan and spoke to Yamaha’s business manager Yoshiaki Takeda. He said they’d be taking a decision within the next couple of days, so was there any way I could see him the following morning. It was almost Christmas, but I jumped on a plane, flew to Tokyo and went with him by train to see the factory. I couldn’t believe how bad things looked – a few old bikes lying around by the entrance, office full of smoke – and sat down to talk. They asked what we wanted and I said we felt a V12 was the way to go, so they took me upstairs to show me drawings for a V12 design study – and that’s how it started. Here I am 30 years later, still working with Yamaha.

“We started testing initially with the existing V8 and the problem there was the fuel injection. If they had used a mainstream system from Bosch or similar, that could have been a really good engine. The V12 proved to be too heavy, unfortunately, and we did one season with it before Middlebridge moved everything away to Milton Keynes. I was left in Chessington, where Yamaha wanted me to be its sporting director – and also to set up a new company, Activa Technology, to do research and development for the road and racing industries. That factory remained active until about 10 years ago.

“After Yamaha’s Brabham deal stopped at the end of 1991, I went immediately to Jordan. Gary Anderson’s first F1 car, the 191, was absolutely beautiful… but the 192 had the same lovely, small radiators and our big V12 wasn’t going to work very well with those. During the British GP weekend I took the head of Yamaha to see engine builder John Judd, whom I’d known for a long time. We then formed a partnership before spending four seasons with Tyrrell and a final one with Arrows. During our last year with Tyrrell, in 1996, I was running Activa, working as Yamaha’s sporting director and also became the FIA’s deputy race director – which was a third hat. And I was part of the steering committee for MotoGP…

“I’d arrive at grands prix in the morning in a Yamaha shirt, have a couple of meetings to discuss what we’d be doing during the day, then change into an FIA shirt and head off to race control to meet race director Roger Lane- Nott. I’d spend most of the day with him, then switch back to my Yamaha kit.”

Here’s one I made earlier: Herbie feels privileged to have been involved with motor sport for decades

Mr Lane-Nott didn’t stay for long, did he?

HB: “He had been a commander-in-chief of nuclear submarines. I’m not sure how he ended up in the F1 role, but Bernie rang and explained they had a new race director who didn’t know much about the circuits: would I help? I said that I already had a job – several – but he told me not to worry about that. Roger tried hard, but he and our medical delegate Sid Watkins didn’t get on so after one season he decided to stop – and Max Mosley suggested Charlie Whiting take the role. The plan was for me to be Charlie’s adviser for a season, but more than 20 years later I was still there. And throughout the whole time I still had my role with Yamaha.

“Charlie and I were aware how lucky we were to be involved so closely, and for so long, with such a fabulous sport. It was a privilege.

“Bike racing versus F1: discuss…

HB: “I absolutely love bike racing. Everybody is friendly, everybody talks to each other and the riders are some of the bravest sportsmen I’ve met – gladiators. They know it’s dangerous and you can really feel the tension on the grid, but then they just get on with it. One guy in Supersport broke his leg badly this season, but he just carried on turning up with his crutches and still raced. They are a different breed. The budgets might not be there in the way they are at the top of car racing, but the enthusiasm and passion are amazing. The atmosphere reminds me of how F1 used to be in the early 1970s, so in a way it has been a bit like going home.”