Aston Martin and LM10 book review

A history to set your pulse racing: if you consider yourself an Aston Martin buff, then prepare to be amazed. Gordon Cruickshank ups his pre-war knowledge

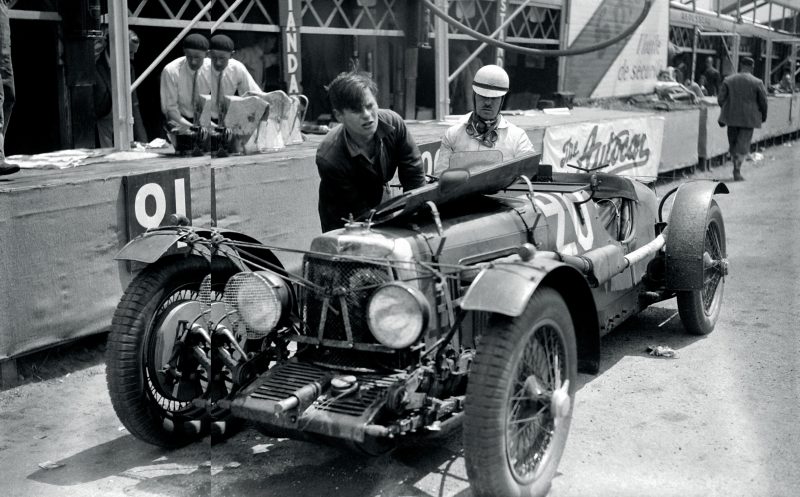

Despite having had its mudguards hastily braced, LM10 finished the 1932 Le Mans race in fifth place

Getty Images

Two movements have been clear recently in the car book publishing world – the rise of self-published works, thanks to the availability of digital publishing programs, and the increasing market share of costlier, lavishly produced volumes. These two streams appear to have come together with this book, which is privately published by the current owners of the car in the title – Aston Martin LM10, effectively the works development car for the company’s pre-war Le Mans racers. Not that this book has been created on a home PC: on the contrary it is professionally produced and smartly designed with quality reproduction and paper stock. Not bad value at £75 either.

They have also chosen soundly for their author: Jonathan Wood has garnered plenty of awards for his car books, not least the RAC Specialist Book of the Year, which we judges awarded him in 2016. This is as thoroughly researched as any of his previous work (even though he said after his last two books that he wasn’t going to write any more…). There’s a connection in that Hugh Palmer previously owned one of the super-rare Squires, subject of a previous meisterwerk of Jonathan’s.

That word ‘and’ in the title is significant: this is not merely a history of the Palmers’ car, important though it is in the marque’s story. It is very much about the people who created Aston Martin, and Wood devotes the first three chapters to the firm’s genesis as Bamford & Martin and its progress through many a financial crisis to a stable period when the Sutherland family took over. Much of the information on the company’s early days, garnered from AM archivists, is apparently published here for the first time. I’m not Aston-literate enough to pick out all that’s new from Jonathan’s wide research, but now I know that Lionel Martin’s wife was known as ‘Calamity Kate’ and that there were ‘Aston- Martin Boys’ before there were Bentley Boys.

Wood offers absorbing diversions into, for example, the disappearing hyphen in Aston Martin and the metamorphosis of the stylised wings on the badge that we know today. Biographies of figures major and minor add to the depth – for instance what happened to ‘Bert’ Bertelli after he walked out of Aston Martin in 1937 – as well as the owners and racers of LM10 itself and other Aston people.

Why should this one car merit an autobiography of its own? One of the three works competition machines of 1932, it has thrice finished Le Mans which would be good enough qualification (and better than some single-chassis histories offered lately). But having been sold after winning its Le Mans class in 1932, LM10 was bought back for the factory’s ’33 entry, to be driven by journalistracer Sammy Davis, and became the works development vehicle on which the team tried many a modification and improvement which went into the showroom Le Mans models and the later Ulsters. This section includes a rundown of Le Mans history including explaining the handicap system and the Rudge-Whitworth Biennial Cup, motor racing’s equivalent of the offside rule… And if I add that he goes on to include a picture of the rather Deco-style Biennial Cup itself, the first I’ve ever seen, as well as the name of its maker you’ll see the degree of research Wood has gone to.

Chassis LM10 is still a public figure, seen here at Brooklands for the marque’s centenary in 2013

Once released again into the wild, LM10 had a string of enthusiastic owners including racers Reggie Tongue and Tony Gaze. Gaze recalls being summoned from a pub because LM10 had dumped a huge pool of oil in the road outside. I know just how he felt – I once ruined the flag stones outside a smart Gloucestershire hotel when my Mk2 Jaguar decided it didn’t need to be full of oil, and my Alfa 164 did the same thing outside a hotel in Bayeux. But I remind myself what vintage stalwart Roger Collings said to me when his 1912 Brixia-Zust dribbled all over the Motor Sport car park: “She’s an old lady – she’s entitled to be incontinent.”

“Wood explains the Rudge -Whitworth Biennial Cup – motor racing’s equivalent of the offside rule…”

Most of her owners have kept LM10 competing, whether racing, hillclimbs, or speed trials, later extending to the Mille Miglia and Le Mans Classic, so there is plenty of coverage of these later eras, though Dr Palmer has decided the car should now retire from competition while still attending events. But I found myself returning again to the car’s pre-war days, and especially its time as a works entry, which offers some very atmospheric photos – for example, some lovely pictures of the team picnicking by the roadside en route to the 1933 Le Mans race, with LM10 parked casually on the verge.

Careful listings of LM10’s race results, as well as those of her sisters, plus adverts and drawings offer visual elaboration, while human tales abound in Wood’s airy text, such as the accident-prone Mort Morris-Goodall falling out of a truck and promptly being stung in the eye by a wasp. Another is about Elsie Wisdom: when her LM7 threw a rod during the 1933 race she explained it to trackside officials with a crisp “Voiture bang!” Which immediately became a team saying, and will probably become one of mine.

Aston Martin and LM10

Jonathan Wood

Palmer, £75

astonmartinlm10.com