Peter was making his mark, so much so he was offered an F1 seat for 1964 by Reg Parnell. But Reg died over the winter and driving an uncompetitive Lotus 24 with few spare parts, the results were desultory. He would not race in F1 again for another seven seasons.

Instead, and save one eyebrow-raising victory against a class field in the F3 support race to the 1965 Monaco Grand Prix in a Lotus 35, Revson turned predominantly to sports cars, racing a Brabham BT8 in the US in ’65 and a Ford GT40 in ’66. For ’67 he tackled Trans-Am in a Mercury Cougar winning twice, at Lime Rock and Bryar Park. He also almost lost his life while testing at Daytona when a puncture threw the GT40 into the air at 185mph. Both Ken Miles and Walt Hansgen had been killed in similar accidents the year before, but Revson stepped out unharmed, a newly fitted roll bar almost certainly saving his life, as it would for Mario Andretti at Le Mans a few weeks later.

But there was real tragedy that season for the Revson family when Doug died in an F3 race in Denmark. If Peter thought of retiring, he kept it to himself.

“An American driver doesn’t have much choice about Indianapolis; he has to be there”

In 1968 he did a winless season of Trans-Am in an AMC Javelin and had his first proper crack at Can-Am, though his Ford-powered McLaren M6B stood no chance against the works M8As of Bruce McLaren and Denny Hulme with proper Chevy grunt. But Revson never gave up. At his funeral Martin Revson buried his last son with the words, “I think that’s the most important thing to remember. He always wanted to do better.”

And better he did. His 1969 Trans-Am efforts improved in a Ford Mustang, while in Can-Am his Lola T163 was probably the second-quickest car out there after the factory McLaren M8Bs.

But in a third discipline, Revson started to show true promise. As he put it in Speed with Style: “An American driver of any stature doesn’t have much choice about Indianapolis; he has to be there.” And there he was at the flag in ’69, finishing fifth, driving a Brabham BT25. What the records show only with further investigation is that he’d started dead last in an uncompetitive car using an underpowered 4.2-litre Repco motor. Later in the season he won heat two of the Indy 200, the only time any Brabham would win an Indycar race.

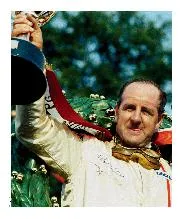

Revson and McQueen after finishing second in the 1970 12 Hours of Sebring

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

The 1970s dawned with Revson now in his 30s, when most racing drivers born for superstardom had already arrived. Peter was still trying. Despite racing in 24 events, once more wins eluded him. Worse, the credit for his greatest achievement of the season went to someone else.

For the Sebring 12 Hours he shared a Porsche 908/2 with its owner, a very real superstar called Steve McQueen – and they damn near won. Uncharacteristically all the Porsche 917s wilted, leaving a dash to the flag between the last factory Ferrari 512S and the 908. Indeed the Ferrari only won because the Scuderia parachuted Mario Andretti into Giunti and Vaccarella’s car. At the flag the works Ferrari led the private Porsche home by 22sec and McQueen took the vast bulk of the credit, partly because he drove with his clutch foot in plaster but mainly because he was, well, Steve McQueen. The truth that Revson was massively faster and had done most of the driving escaped fans entirely. In fact the car came second despite and not because of McQueen. Had Revson shared with a driver of similar calibre, the Ferrari would never have got near them.